“Demand the sound of paper! Echoes of our REAM-IFY binary! Dada laughter in every perforation, Nietzschean yodel in every typewritten stroke. Dance, my friends, dance within nonsense stanzas and absurdist sonnets. REAM-IFY, mummify the rational!”

The Infinite Manifesto

Among the best parts of DADA, a very successful edition of the UNSOUND festival in Kraków, Poland, which ran from 1-8 October, were those moments that embraced the theme of Dada in spirit rather than in explicit dialogue with Dada as a historical movement. Much of this turned on the element of surprise, often in the form of short interventions of about 10 minutes between the longer sets. Not for nothing, but many of the festival’s most humorous moments came in this form, adding much needed levity to what could often be self-serious and heavy, particularly as more traumatic themes lurked in the background. Afterall, we are still recovering from a global pandemic and living in the shadow of the ongoing Russian invasion of Ukraine, Poland’s neighbor, to say nothing of the latest violence in the Levant which broke out during the final days of the festival. That said, the explicit historical references, when they cropped up, were also significant and proved to be equally memorable, particularly when contemporary artists provided new soundtracks to historical films.

The actual shadow theme of the year, however, was DATA, with so-called Artificial Intelligence and machine learning a recurrent theme, tool, and topic of discussion. Various artists deployed AI as part of their practice, creating generative sound poetry, insane mash-ups, and poignant works of sound art. As part of the discourse programming, several panels featured frank discussion of the opportunities, risks, and ironies of the current explosion in machine learning and the subsequent development of (often) exploitative attempts at cashing in. And we cannot forget AIAD, the festival’s slightly tongue-in-cheek Artificially Intelligent Artistic Director. AIAD (ostensibly) made various suggestions to Unsound’s human directors, some of which were taken—for instance, the In(ter)ventions—while others were not—such as the suggestion that co-founder and co-director Mat Schulz should sing his opening remarks accompanied by an acoustic guitar. AIAD also produced daily write ups throughout the festival, as well as The Infinite Manifesto quoted in the above epigram, and curated a playlist for Freak Zone for BBC’s Radio 6, before being (un)ceremoniously fired at the end of the festival for overstepping their bounds (allegedly offering spots on the all-AI 2024 edition without authorization).

The actual shadow theme of the year, however, was DATA, with so-called Artificial Intelligence and machine learning a recurrent theme, tool, and topic of discussion. Various artists deployed AI as part of their practice, creating generative sound poetry, insane mash-ups, and poignant works of sound art. As part of the discourse programming, several panels featured frank discussion of the opportunities, risks, and ironies of the current explosion in machine learning and the subsequent development of (often) exploitative attempts at cashing in. And we cannot forget AIAD, the festival’s slightly tongue-in-cheek Artificially Intelligent Artistic Director. AIAD (ostensibly) made various suggestions to Unsound’s human directors, some of which were taken—for instance, the In(ter)ventions—while others were not—such as the suggestion that co-founder and co-director Mat Schulz should sing his opening remarks accompanied by an acoustic guitar. AIAD also produced daily write ups throughout the festival, as well as The Infinite Manifesto quoted in the above epigram, and curated a playlist for Freak Zone for BBC’s Radio 6, before being (un)ceremoniously fired at the end of the festival for overstepping their bounds (allegedly offering spots on the all-AI 2024 edition without authorization).

Prior to the start of the festival, I broke down the programme in fine detail, highlighting my preferences and outlining a kind of schedule for myself (and anyone else who might happen to have been in Krakow for this edition). During the festival, I posted daily recaps and commentary via the ACL newsletter, totaling nearly 20k words, as well as quite a few photos and the occasional video, over the eight days. Written for our paid supporters, with a bit of general preamble for free subscribers, I was able to capture my impressions as they occurred, and experiment with tones I don’t usually let sneak into what I write here. It was inevitable, as I was literally delirious, finding moments to write late at night and in between a very full schedule. Now that the marathon is over and I’ve had a bit of time to process everything that occurred, allow me to offer some more general reflections, reviewing the most significant performances and meditating a bit more deeply on this year’s theme.

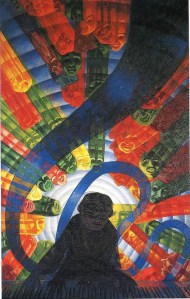

Luigi Russolo, La Musica (1911)

MOURNING GLORY

Let’s begin with the heavy stuff then, as is so often the case, with history. The discourse programming began with a Luciano Chessa’s “Futurism, Dada, and the Noise in Between,” on the relationship between Dada and Italian Futurism. As I predicted, the sonic link between Futurism and Dada rests on sound poetry, and on a few particular connections between the German-French movement and the Italians. While he noted that the dadas were more radical from start, beginning with Hugo Ball’s manifesto of 1916 that critiqued rhetoric itself, most of the focus remained on Italian Futurism, and in particular Luigi Russolo, considered the father of noise music. As the inventor of the intonarumori noise instruments, Russolo made “music that is not exactly music,” and despite identifying as a musician, was not regarded as such even by his fellow Futurists. Rather Russolo was a painter, though he studied neither painting nor music. That said, his brother attended a music conservatory, and more aptly their father was an organ builder and tuner, which was a crucial influence on Russolo’s work as an inventor. Chessa spent a good deal of time discussing the following painting from 1911, reading into it Russolo’s coming philosophy of composition, which sought not to further divide the 12-tone octave into half tones and quarter tones and such, but to transcend division all together, focusing instead on continuity. While I was somewhat critical of the ways in which Chessa downplayed Futurisms close links to fascism, there is indeed something radical about Russolo’s move from “the fragmentary to the continuous,” and thinking of his famous intonarumori as proto-oscillators unlocks something foundational to contemporary music production. Chessa also explained that Russolo thought of his work as pursuing the future of visual arts in sound. And in this, he shared an interest with the poets of both Futurism and Dada, who each pursued polyvocal poetry and concrete, non-semantic explorations of the voice in ways that were truly original.

Rrose (courtesy of Unsound)

Musicians also directly evoked avant-gardes of the past. Closing out the opening night’s event at Łaźnia Nowa Theatre, Seth Horvitz’s (Sutekh) gender-fluid alter-ego Rrose performed alongside a reworked version of surrealist Man Ray’s 1926 short Emak-Bakia. They chose their most enduring moniker as a reference to Marcel Duchamp’s feminine alter-ego, Rrose Sélavy, her name itself a pun on a on the French adage “Eros, c’est la vie” (Love, that’s life). Much of the early part of the set explored a low drone, gradually building out and receding in seeming dialogue (sometimes) with the film, which began as abstract shapes, moving on to images of a fish, then a rotating geometric junk statute, pigs, a car driving down a road, and on and on. While abstract and non-narrative, the black and white film played with contrast and had lots of movement, maintaining visual interest. At one point the sub bass was so intense that it was shaking the floor, indeed shaking the whole place such that I had to check to make sure the lighting and sound rigs weren’t about to tumble down. This all occurs just as the woman on screen, who had had a blank expression dispute her wide eyes, finally smiles widely, in a disconcerting way (at least that’s how I felt given the bass accompaniment). The film returned to abstraction painted layers, as the rhythm of the music divided and expanded again as well.

Okkyung Lee (courtesy of Unsound)

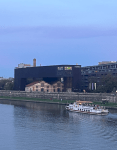

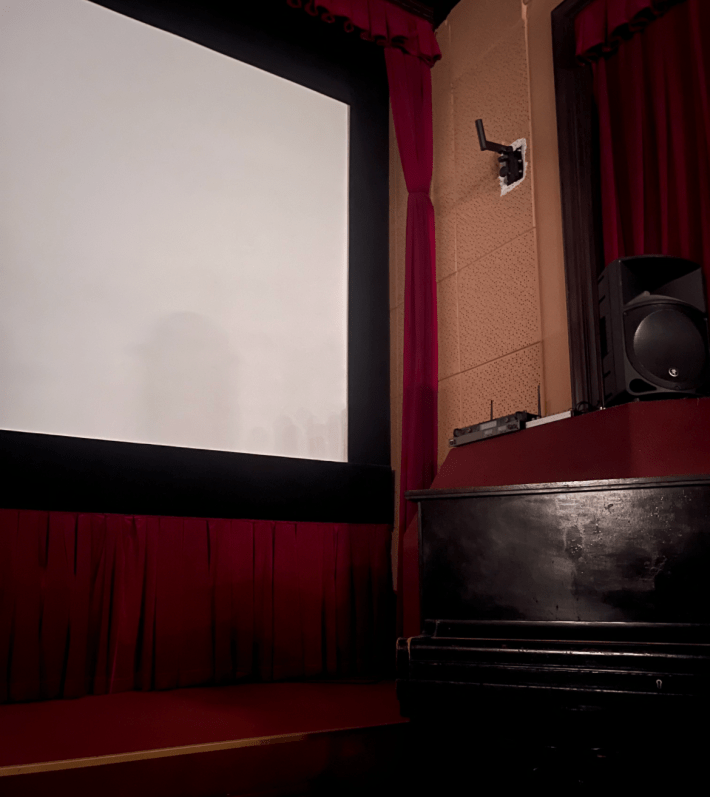

Later in the week, Okkyung Lee performed alongside selections of other Dadaist films, at Kino Kijów, a modern cinema built in the 1960s that was at the time the largest in Poland, and continues to host the Krakow Film Festival, and also “opera, dance & cabaret, with a film club & a cafe.” Kijów is the Polish name for Kyiv, and after speaking with my new Polish friend Walter we’ve concluded that the name was meant to evoke a more cosmopolitan city, to give the theatre a more high-class and exclusive connotation. So while we have various connections to history here, I think we may also have a glimpse of the future. Movie theatres are underrated concert venues, and as they struggle to draw crowds back following the pandemic, music is an obvious alternative. Theatres have comfortable seats, encourage the purchase of refreshments, and have excellent sound, in fact often the most state of the art frequency response and an absence of reverb. Of course cinemas are primarily designed for visual presentations, and all three acts on the program were A/V shows.

Lee’s first selection was a film by Hans Richter, a version restored in the 1970s. The opening title screen announced that the original sound version of the film had been destroyed by the Nazis, who classified it as “Degenerate Art,” and thus it lent itself to this treatment. As with Emak-Bakia, Richter’s film was full of clever visual tricks that despite their relatively simplicity, I often find to be more interesting than contemporary digital AV. So many of these techniques are quite basic; a scene is repeated, run backward, looped, mirrored, rotated, etc, but despite the simplicity, the visuals can be enjoyable and even quite complex. The second, shorter film was also by Hans Richter, this time a geometric parade of white squares and rectangles of different sizes, moving in and out of depth against a black background. Less surreal than the preceding, it still had a kind of strange charm, and reminded me of the avant-garde ancestor of the kind of vignettes I remember seeing on Sesame Street of PBS as a small child in the 1980s. And lastly was Ballet Mécanique (1923–24), a classic work by Fernand Léger and Dudley Murphy (with cinematographic input from Man Ray). It began with simple geometric solid color shapes—blue, yellow, and green squares, circles, and triangles—moving in various configurations, eventually achieving a kind of psychedelic effect. Dadaism was under the influence of Cubism by this point, and the focus on machine movement evokes the work of Francis Picabia and others who were fascinated by industrial engineering. Much of the imagery focused on machines, including rotating whisks and pumping pistons, but as part of a montage that also included close ups of a woman’s face, shots of her eyes and mouth, opening and closing, leaning back and smiling, all focused on choreographed movement. Throughout, Lee’s cello was in dialogue with the images, sometimes augmenting and other times in juxtaposition, deploying a variety of squeals, scrapes, and cries. She would occasionally use a laptop, seemingly adding backing tracks that sounds like rhythmic clicks or vibraphone notes, which added some sense of variety to the arrangements which were otherwise her furious cello.

Marginal Consort (courtesy of Unsound)

Dialogue between past and present is one means of relating to the festival’s theme. In other cases the connection to the historical avant-gardes is more direct, as is the case with Japan’s Marginal Consort, which made their presence at the festival that much more significant. The group formed out of the ashes of the East Bionic Symphonia in the 1970s, under the influence of and tutelage of Takehisa Kosugi, a participant of the loose Fluxus movement. Listeners of Sound Propositions will recall my conversation with Musica Elettronica Viva’s Alvin Curran. MEV also took particular inspiration from Fluxus composers, such as Giuseppe Chiari and Takehisa Kosugi, who made a strong impression on the young ensemble for how they combined simple compositional strategies with theatrical actions. Curran recalls watching Kosugi roll around inside a leather gym bag with an acoustic guitar within view of the Pantheon as a moment which particularly transformed his concept of musical performance. Both the form and content of Marginal Consort’s performances are similarly radical. Marginal Consort have played one concert annually since 1997, always a minimum of three hours, so there is something about their work that centers specificity, duration, and endurance in a way that transcends typical performances. Their concert was held at the Museum of Engineering and Technology, a large hangar surrounded by historical trams and trolleys, with the audience filling in the space as the four performers were set up with their noise tables in the corners. I for one always appreciate atypical audience configurations that disrupt the expectation of shared orientation.

Fluxus was itself a kind of neo-dada movement, and in some ways might be understood as the culmination of an avant-garde genealogy that runs from Italian Futurism through Dada and Surrealism and Situationism, up to Happenings and Fluxus. Each member had distinct objects and roles, with some overlap, but if I can generalize, moving counter-clockwise: some kind of guitar / lute (sometimes bowed) and various objects, including a tape measure, which was violently whipped about at some point; various percussive objects, including drums and bowls; computer and electronics with an array of flutes; and various objects, including metal sheets, tubes, sticks, springs, and a very large piece of wood. Their interactions could be funny, serious, poignant, off the cuff, theatrical, and performative, sometimes all at the same time. Especially at the beginning, various members would produce a series of repetitive actions, events, or noises, interacting with (or in juxtaposition) to what the other members were doing, slowly pushing and pulling and evolving, like a Fluxus drum circle. Many of the sounds were acoustic in nature, for example bouncing a tall piece of wood off the floor, shaking a tape measure or a metal sheet, banging out a plodding rhythm on a drum, humming loudly, etc, but many of these sounds were amplified, with a few sounds of electronic origin as well, some simple signal processing, maybe some field recordings and feedback tones. Endurance is one way to achieve a state of meditative delirium, and while I can’t say I know much about what the group thinks they’re doing, that’s how I experienced it as an audience member, and it was surely one of the highlights of the festival. Like with much of this edition, the theme of Dada allowed us to sidestep some of the more serious or pretentious readings. One bro jokingly tried to Shazam an erhu solo as he left the venue, which cracked me up.

Fluxus was itself a kind of neo-dada movement, and in some ways might be understood as the culmination of an avant-garde genealogy that runs from Italian Futurism through Dada and Surrealism and Situationism, up to Happenings and Fluxus. Each member had distinct objects and roles, with some overlap, but if I can generalize, moving counter-clockwise: some kind of guitar / lute (sometimes bowed) and various objects, including a tape measure, which was violently whipped about at some point; various percussive objects, including drums and bowls; computer and electronics with an array of flutes; and various objects, including metal sheets, tubes, sticks, springs, and a very large piece of wood. Their interactions could be funny, serious, poignant, off the cuff, theatrical, and performative, sometimes all at the same time. Especially at the beginning, various members would produce a series of repetitive actions, events, or noises, interacting with (or in juxtaposition) to what the other members were doing, slowly pushing and pulling and evolving, like a Fluxus drum circle. Many of the sounds were acoustic in nature, for example bouncing a tall piece of wood off the floor, shaking a tape measure or a metal sheet, banging out a plodding rhythm on a drum, humming loudly, etc, but many of these sounds were amplified, with a few sounds of electronic origin as well, some simple signal processing, maybe some field recordings and feedback tones. Endurance is one way to achieve a state of meditative delirium, and while I can’t say I know much about what the group thinks they’re doing, that’s how I experienced it as an audience member, and it was surely one of the highlights of the festival. Like with much of this edition, the theme of Dada allowed us to sidestep some of the more serious or pretentious readings. One bro jokingly tried to Shazam an erhu solo as he left the venue, which cracked me up.

On a different note, the festival’s hangover curing morning concerts, typically called “Morning Glory” but here rebranded as GORNING MLORY—because DADA—took a more immediate view of history, as in, recovering from the prior evening. There were three performances under this heading, all in a crowded medical college with too-steep staircases and crowded rows, featuring the Polish guitar and percussion duo OPLA, a somber set from New York’s 703, and Jules Reidy’s dulcet dream pop grounded in their customized microtonal guitar. In a similar vein were the Ambient Brunches hosted in the restaurant of the chic PURE hotel, featuring two hour DJ sets from claire rousay and Antonina Nowacka. In their own way, each performer created a space for reflection and dissociation, the perfect alternative to the more demanding programming that filled our evenings, whether in contemplation or revery.

The two films I was saw during the festival were also both, in their own way, historical testaments, both at Kino Pod Baranami (“Public Cinema Under the Ram), a theatre in Krakow’s historic central square. Stand By For Failure, Ryan Worsley’s found-footage Negativland documentary, fittingly documents the history of the long running group, who have sadly lost several core members in the last decade. You can watch the trailer here, and I’d encourage you to catch it if it will be screening in your city. I don’t know much about Ryan Worsley, but she pulls off a truly outstanding feat of editing worthy of her subjects (themselves well-known for their editing skills). Stand By For Failure has a clear narrative, and is basically chronological, from David Wills (aka The Weatherman)’s childhood tape recorder through the foundation of the “band,” meeting Don Joyce and joining his radio show, the fake press release linking the band to Minnesota ax murders, the whole U2 lawsuit, their subsequent championing of fair use, and evolution into the 21st century, as Jon Leidecker (Wobbly) becomes an official members, and three of the founding members die in quick succession. The film comes straight up to the present, showing the band preparing for 2021 live streams and masked touring. But it is far from a conventional documentary, rather an audio-visual collage, and it’s about Negativland, after all, so it largely leaves the meaning making up to the individual viewer. No explicit psychologizing or theorizing here, even if Marshall McLuhan makes repeat appearances. A touching and creative tribute to a pioneering group of sound weirdos.

Ukrainian artist Heinali’s film version of Kyiv Eternal uses documentary footage to very different effect. Heinali’s music is a gorgeous kind of blend of field recording textures and rhythmically manipulated loops and distortion, not unlike the early work of Fennesz or Tim Hecker. Kyiv Eternal, the album, was composed using field recordings Heinali had made in Kyiv prior to the war, on the way to his studio and just moving around the city as one does. These fragments have taken on new meaning since the war began. For the accompanying film, Heinali solicited pre-war videos from Kyiv citizens, quotidian slices of life that have also taken on new power as a result of the disruptions of war. Trains moving, people celebrating birthdays and weddings, having fun dancing and playing music, the flux of the seasons, all feels both celebratory and mournful in turn. I generally disapprove of vertical format (phone) videos used in TV or cinema, but it allowed the film’s editors an additional means of transformation and contrast, sometimes showing the same shot in different scales. These memory capsules of prewar Ukraine also allow for a rhythmic montage to interplay with the music itself. So we get a somber but affirming sense of Kyiv as a vibrant city full of play, humor, life, full of animals, and children, and music and food and architecture. Whatever happens in the future, Kyiv’s spirit will persevere.

Kino Pod Baranami (photo J. Sannicandro)

LAUGHTER IS THE BEST MEDICINE

Despite the depressing reality of war—that for now many of these unadulterated expressions of joy exist in the past—there is nonetheless something profoundly moving about simply bearing witness to them. We could all use more laughter, not as an escape but as good medicine. This underscored for me another important thread in this edition Unsound; so much of the programming wasn’t just fun, but funny.

There is not enough humor in music. Besides novelty acts like Weird Al, the most reliable source of humor comes in punchlines that are a feature in many styles of rap. It’s certainly not a recurrent theme in most experimental music. Perhaps this makes some amount of sense. Comedy, as a general rule, doesn’t age nor travel well. But maybe that’s changing a bit. The theme of DADA certainly invited some comedy, and many of my favorite moments of the festival were those that made me laugh out loud.

Comedy has always been part of what makes Negativland’s music work. In my interview with the group, to appear in a future installment of the Sound Propositions podcast, Mark Hosler explains that if an edit makes them laugh they’ll keep it. But that alone isn’t enough, if the message starts to seem too clear they’ll be sure to add another element of confuse things, which is a form of comedy in its own right.

Negativland (courtesy of Unsound)

Negativland were the first performers on the opening night of the festival, and their set was preceded by an announcement from the festival’s Artificially Intelligent Artistic Director (AIAD), rather than the festival’s human curators who would normally handle this role. The announcement was played in English and Polish, and it was a more than fitting prologue to a Negativland performance.For this live performance, backed by live visuals from SUE-C, Negativland consisted of Mark Hosler, on mixer and various pedals and electronics, and Jon Leidecker (Wobbly), with an array of tablets and iPhones dedicated to triggering and manipulating the vocal samples that are so often at the core of the group’s aesthetic. Hosler would end up staying in Krakow due to health issues, while Leidecker continued on tour on his own with remote help from Negativland members back in the States, making this performance all the more special.

Both visuals and audio had a strong collage aesthetic, and so juxtaposition and movement are essential to making sense of the experience. That said, a fair amount of nonsense is injected in case the point is a bit too clear. This has the dual effect of being both humorous as well as keeping the work open-ended and enduring, as work that is too clear or didactic largely tends to fall away. Pleasing kalimba melodies launched the set, which gradually incorporated sub bass and synth sounds, tied together by the group’s (very much not) trademarked vocal collage. The theme seemed to revolve around gaming and play, in the broad sense but also about video games and their specific place in contemporary culture and media. One particularly successful juxtaposition came when a voice stated “me and my brain are one” as another voices added “or zero,” which got significant laughs from the crowd.

Leyland Kirby (courtesy of Unsound)

Another of my favorite memories from the festival was one of the funniest and most surprising, and also probably the most impromptu. When Dawuna cancelled at the last minute, Leyland Kirby (V/vm / The Caretaker), who has been a longtime presence at Unsound and Polish resident, stepped up for a set billed as “Master of the Absurd.” Indeed. Kirby walked onto the stage like a wrestler, wearing a shiny pink shirt and a grotesque pig mask (a call back to V/vm’s live show), doing a lip synch stand-up routine to recordings of dada Billy Basinski, complete with canned laughter. Truly hilarious, and in case you didn’t recognize Basinki’s voice, which was maybe pitched down a cent or two, his Wire cover and other photos were cycling through the screen behind Kirby.

I would have been surprised if Kirby had delivered a traditional musical set. I thought Kirby retired The Caretaker even before he creeped out Gen Z kids on TikTok. But then again, he is scheduled to play Unsound New York in December with Moor Mother, billed as The Caretaker, so who knew what to expect. This bait and switch just made the entire performance that much more hilarious. Ah, OK, he’s doing a dada, I said to myself. That makes sense. “Master of the Absurd” did suggest we wouldn’t be getting a standard performance.

Once the Basinski bit ended, Kirby cued up Human Resource’s techno banger, “Dominator,” sat down and drank from a bottle through said pig mask as the song played. He then dropped the mask and began to lip synch karaoke Elton John’s “Rocket Man,” live from Glastonbury earlier this year. Again, the live crowd noise from the recording just made the bit even funnier, though the crowd at Manggha was eating it up as well. Since it was a live version, it seemed to never end, and during the extended piano solos, Kirby sat down on a different chair and pretended to bang it out. His lip synching was pretty on point, for what it’s worth, hitting all the ad libs, never coming in late, and only once seeming to cut off a split second early. This was followed by even more Elton John, this time the song from the Lion King, which again got the crowd in the right mood. The shiny pink shirt comes off, white DA DA tee underneath to remind us of the vibe. “Can you feel the love tonight?” We did. With the whole crowd swaying to the beat, Kirby fully went for it, working the crowd, always reaching out and emotionally pretending to belt it out with full Disney sentimentality. As a finale, he played a trap remix of “It’s just a burning memory” from YouTube, during the course of which a delivery boy appeared on stage to deliver a bouquet of flowers. Caretaker Out.

Anna Zaradny (courtesy of Unsound)

IN(TER)VENTIONS

Many of the festivals most memorable moments were similarly last minute changes, unannounced surprises, or billed as short “Interventions.” The first of such came from Warsaw-based improvisor Anna Zaradny, immediately following Negativland’s opening performance. The crowd was instructed to leave the main theatre, but before long Zaradny led the stragglers to the bar, playing sax like a pied piper in a shiny metallic suit. Saxophone sounds were being diffused via a multichannel spatialization, mostly consisting of key noises and pops, sounds which migrated with her from the theatre to the bar. For about seven minutes, Zaradny performed in the middle of bar crowd, enough time for the stage techs to further convert the theatre space. Once back in the mainroom, Zaradny then assumed a position on a bean bag, in front of the risers of chairs that remained, and performed the bulk of her set, with live saxophone and voice interacting with backing tracks, and being manipulated via a few effects pedals. It was an impressive performance, and as I mentioned in my preview, discovering Polish artists I hadn’t heard of is always a highlight of Unsound.

Not quite a band, Dadabots appeared at various moments throughout the festival, as sort of hackathon punks deejaying AI breakcore. The duo “crate dig” their own AI generated experiments, which they stream 24/7 via Twitch and YouTube. Sonically they evoke technical metal/hardcore/grind/ and drum n bass. It’s not quite hyperpop, but there are some shared elements. I mean, 100gecs are just iPad pop punk for Gen Z, right? I also hear similarities with FireToolz and some aspects of more recent OPN. Not so aesthetically similar to the music of Holly Herndon, but I noticed her avatar in the visuals, and perhaps her voice was being interpreted as well, given their shared interest in machine learning. There would be moments of ambient interlude, the kind of thing you might have heard in jungle before a break would come in. There’s a bit of breakcore influence for sure, and overall, the music was dynamic and high energy. I think one of the members dropped to the ground to do push ups and kicked the air, while the other, on crutches, just pumped his multicolor crutch above his head. Wild, unpredictable music, but it managed to cohere. It’s not something I’m sure I’d listen to this at this stage in my life, but it was a fun set, smartly kept to a tight 20 minutes because it’s a gimmick that wears thin.

The Magician, basking in applause (courtesy of Unsound)

Other interventions were a bit more tongue in cheek. At the Filharmonia Krakowska, in between the two main concerts, a corny magician came out and performed cheesy illusions to rapt applause. But the best interventions split the difference. Paulina Owczarek, a Krakow-based sax improviser and founder and conductor of Krakow Improvisers Orchestra, performed another sax intervention at the Manghha museum between longer sets. During one of the club nights at Kamienna 12 railyard, Heinali did a short presentation of Synthtap, revolving around a tap dance synth routine. And Tobias Koch performed briefly in between the main events, an unannounced intervention that involved him walking around the floor of the venue swinging a parabolic microphone to generate feedback, eventually singing in an operatic style, a performance that was much more affecting than that simple description can convey.

Heinali’s Synthtap (courtesy of Unsound)

That same show on the final night of the festival at ICE, a modern concert hall and convention center on the river just south of the Old Town, also began with the fourth and final performance by Machine Listening. Comprised of artist-researchers Sean Dockray, James Parker, and Joel Stern, Machine Listening use some sort of custom software based on natural language processing to manipulate text to speech in rhythmic and funny ways that seem to be evoking the spiriting of both dada and data. Their final iteration was dedicated to the work of Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, one of the most interesting dadaists, with all the contradictions that entails. If one of the goals of the avant-garde was to blur the line between life and art, even collapse the distinction entirely, then the Baroness was truly the embodiment of dada, and I was glad that she was finally mentioned, seeing as the historical avant-garde was such a sausage party. One of Marcel Duchamp’s patrons, she is now accepted to be the true originator of the readymade, rather than him. Machine Listening vocalized the text of a poem the same way it had previously, but somehow the effect was more pronounced. The text of the poem was visible, and the cursor jumped around in the usual way, but then a yellow highlight appeared, and the text quickly scrolled back up to the top and back again, “reading” the text as it moved across the highlight. This kind of transparency of the workings of the project demystifies the process, make it more humorous, and crucially draw the listener in. One of the Baroness’ assemblage works, God (1917), originally credited solely to Morton Livingston-Schamberg, a piece of curved pipe affixed to a wooden slab, appeared on screen as well.

Detail of Machine Listening (courtesy of Unsound)

Like Dadabots, Machine Listening appeared multiple times throughout the festival, with four ~10-minute performances, as well as a sound art installation on the top floor of the Center for Democracy. In each instance, their performances involved vocalizing speech from several texts, which were visualized on the screen so the audience could have some sense of what they were up to, rather than just listening to nonsense. In the three performances I witnessed, the texts were either based on historical dada texts, or else derived from AI interpretation of that text, as was the case where a work by Kurt Schwitters resulted in the programming vocalizing some variation of “Oh God, Oh Good,” for ten minutes, words that do not even appear in the original, and yet this was both in the spirit of dada, somehow, and also managed to be the most engaging and funny of their performances.

Machine Listening’s multi-channel sound installation, After Words (2022), demanded more prolonged contemplation, and perhaps relatedly was less fun, but more thought provoking. As I mentioned previously, ten minutes is about all one can take of such a work, as there’s only so much to explore in a single text without becoming overly annoying. But After Words is something quite different, a series work of art that subtly draws the listener’s attention to the ways that our devices are always listening to us, and learning from us. Because Machine Listening explores machine learning systems, this piece, a kind of multi-channel collage of codespeak, also draws our attention to the ways our devices have learned to speak by listening to us. For instance, one part of the script describes Amazon’s internal rules for Alexa (don’t use Alexa as a verb, Alexa is not plural, etc), but it was the segment on “wakewords” that most struck me, evoking the “wakewords” that can wake a “sleeping” virtual assistant (“Hey Siri,” “Alexa,” “Hey Google,” etc) this use of the word struct me as significant in wider contexts.

The DADA theme allowed artists and audience to embrace delirium over despair, to luxuriate in absurdity. The short interventions played an important role in maintaining a sense of dynamism in breaking up the rhythm of the longer performances, but those longer performances were no less powerful. The three-hour endurance test that was Marginal Consort’s performance couldn’t help but have a hypnotic effect. Polish experimental vocalist and composer Antonina Nowacka demonstrated the potential of slow music with her two-hour Ambient Brunch DJ set. Much as she manipulates the layers of her voice in her solo work, playing with time and texture, her set tended towards long compositions, which she subtly mixed, not only filtering out frequencies with EQ, but subtly yet actively playing with their pitch. I caught records by Ash Ra Tempel, some Japanese soundtrack music, various Asian folk musics, and lots of strings, though recognition seemed beside the point.

I know it’s become their usual bit, but there’s still something absurd about Autechre performing in the dark. I agree that the absence of visuals—in fact the absence of light, which also discourages the audience from looking at their phones or taking videos—can engender a different, even deeper, appreciation of sound. But when Francisco Lopez blindfolds his audience they’re seated, which also allows him to play with the orientation of the audience, often seated in a circle facing away from him at the center. Autechre, however, just turned off the lights in the venue. Despite everyone being handed a double sided flyer in English and Polish informing us that the duo would perform in total darkness and that once the show begins we were not to move, many people pushed their way forward or left throughout. As I’ve argued elsewhere in great detail, live musical performances are overly committed to the paradigm of the stage. There is no reason that an audience for live music must all be oriented in the same direction. For this reason, I find a lot of visuals superfluous and even detrimental, so I like the fact that Autechre perform in total darkness.

I know it’s become their usual bit, but there’s still something absurd about Autechre performing in the dark. I agree that the absence of visuals—in fact the absence of light, which also discourages the audience from looking at their phones or taking videos—can engender a different, even deeper, appreciation of sound. But when Francisco Lopez blindfolds his audience they’re seated, which also allows him to play with the orientation of the audience, often seated in a circle facing away from him at the center. Autechre, however, just turned off the lights in the venue. Despite everyone being handed a double sided flyer in English and Polish informing us that the duo would perform in total darkness and that once the show begins we were not to move, many people pushed their way forward or left throughout. As I’ve argued elsewhere in great detail, live musical performances are overly committed to the paradigm of the stage. There is no reason that an audience for live music must all be oriented in the same direction. For this reason, I find a lot of visuals superfluous and even detrimental, so I like the fact that Autechre perform in total darkness.

Screenshot of Models live stream

But in this case, the crowd was still standing in a large auditorium, oriented in the same direction, except we were standing together anxiously in the pitch black as some folks continued to push their way forward (for what purpose I couldn’t tell you), or push their way out due to the discomfort (despite being warned in advance). In a perfect world the crowd would have collectively agreed to sit down, but let’s be honest, for such a thing to work successfully we would have had to have been instructed to do so. In our world, we could have at least provided some chairs or other seating arrangements. I’m glad I was able to experience Autechre live, but again, if you’re going to play pitch black, why stick to the traditional concert orientation?

If you are going to stick to a traditional stage orientation, then the visual focus should have some conceptual significance, especially since electronic music doesn’t conform to the gestural spectacle of live instrumental performance. For example, Lee Gamble premiered his new record Models (Hyperdub) with some conceptually resonant choreography that was thought-provoking on its own terms, while deepening our appreciation of the music. Parts of Models were recorded at the GRM in Paris, and the models of the title refers to, at least in part, voice modeling software drawing on synthetic and AI generated “voices.” Gamble explores these disembodied voices that, as far as I can tell, are completely lacking in semantic context. For the debut performance, commissioned by Unsound and Spain’s Sónar festival, Candela Capitán choreographed three dancers (Julia Romero Soriano, Mariona Moranta Capllonch, and Virginia Martin Mateos) in an embodied and weighty performance that served to augment and counterbalance Gamble’s record. The three dancers, in high heels and white body suits, each wore a black harness around their hips, connected to two chains which ran up to the rafters behind them. They writhed and posed in various contortions, before pulling out smartphones seven minutes into the show, at which point they began live streaming via Gamble’s Instagram profile. What kept this from being cheesecake was in the details. I found the whole bendy, almost grotesque, poses with arched backs and straight legged heel moves a bit reminiscent of a surreal stripper routine, the whole thing seemingly trying to evoke sex appeal while also simultaneously undercutting it with the flat affect and literal chains. Towards the end of the performance each woman took turns running and leaping towards the crowd, flying just a few inches off the ground before being pulled back to earth.

Lee Gamble’s Models (courtesy of Unsound)

Unsound’s late-night program, divided in two room across the vast Kamienna 12, a former rail depot, were most likely to embrace the unusual, letting the dance floor manifest as a site of celebratory escapism without sacrificing experimentation and outright weirdness. The small second stage, on the opposite end of the railyard from the main stage, was were I found myself most often, and from what I could see was where the crowds were most worked up. While I’ll admit that Lust$ickPuppy makes the kind of music that makes me feel old, there’s no denying the impact of her high-energy genre-defying music, amplified by her stage presence and costume, referencing punk, queer glam, and BDSM culture. Of course, more conventional DJs were still able to whip up the dance floor as well. Dj Babatr emerged from the slums of Caracas in the late 90s and early 00s, pioneering a local style known as raptor house, which fused ghetto tech, euro trance, and Afro-Latin styles, a genre that has only recently got attention outside of Latin America. From Babatr’s expert skills as a technical DJ who could rock the main room, I drifted back to the small for an absolutely bonkers set from EYE, best known for his time in Boredoms. We often hear about freeform DJ sets and style clashes, but EYE’s set was truly wild, full of aggressive beats, wild squelching electronic noise, and outright screaming. Another notable set came from 3Phaz, a Cairo-based DJ part of the last decades fascination with North African styles in a club context, has recently released Ends Meet on Discrepant, one of my favorite eclectic labels of recent years, who I think of as the next evolution of the “world music 2.0” of Sublime Frequencies.

Shapednoise & Sevi Iko Dømochevsky (courtesy of Unsound)

Watching Japan’s Meuko Meuko pummel the crowd in the main room helped me recognize a trend towards higher BPMs and more aggressive percussion. While still in the techno wheelhouse, I’ve noticed that more and more artists seem to be more inspired by extreme metal genres than jungle or dnb. The inhuman speed and precision of the drum programming can be deeply disconcerting, especially at a tempo that is too fast to dance to. Several other acts I witnessed at Unsound have embraced this combination of frenetic beats and deep bass. Maybe the antidote to the “soothing” and “restorative” ambient trend of the pandemic is to go in the opposite direction. Meuko Meuko’s visuals, however, did nothing for me, I find myself allergic to this style of digital imagery, with hyper-real lighting and textures, rotating objects and text against a surreal background, akin to ’90s screensavers and Mortal Kombat loading screens. But as always, your mileage may vary, especially if you weren’t yet born in the 1990s. I was more interested in Sevi Iko Dømochevsky’s live visuals for Shapednoise, which included not only a projector but various size flat screen monitors askew around the stage. Shapednoise presented his new record, Absurd Matter, his first after an extended absence, a record that fuses noise with hip-hop vocalist guests, similar in spirit but quite different from his techno post-punk origins. But while unfortunately I couldn’t fully appreciate the visuals from my vantage point in the crowd, the bass didn’t have that problem in reaching me.

Kill Altars vs Dreamcrusher offered a similarly eclectic mix of high-energy influences, though to very different effect. As I’ve mentioned, the smaller second room was consistently grittier, noisier, more fun, and more packed. Kill Altars have released records on Hausu Mountain, and their being on same label as Mukqs and FireToolz seems fitting, if only because their music is such a genre-defying explosion of energy. Front-woman Bonnie Baxter carried the show with the intensity of her performance, matching that of their beefy shirtless drummer, the artist Hisham Bharoocha (Boredoms, Black Dice, Lightening Bolt). At times reminiscent of a kind of pop punk dnb, at others they could evoke RATM and Melt Banana, with hardcore breaks on live drums and electronic treatment supporting Baxter’s dynamic vocal performance. Eventually, Dreamcrusher got involved, and the triple vocal attack made me wish they’d actually overlapped more. As Dreamcrusher transitioned to a solo set, the crowd was overwhelmed by strobe lights and fog, with the vocalist often wading into the adoring crowd while screaming in our faces with a flashlight affixed to their microphone, making for a dramatic and cathartic show.

Dreamcrusher (courtesy of Unsound)

The Shape of Junk to Come

I was struck just how many performances this year involved live instrumentation, often in duos or larger ensembles. I recently wrote about the return of guitars in experimental music, but I think live rather than sequenced percussion is emerging as an even more important trend, one I welcome wholeheartedly. I wasn’t totally convinced by Ziúr’s improvised take on her album EYEROLL, with help from Elvin Brandhi and Iceboy Violet, but Ziúr’s live drums and electronics and screamed vocals, supported by the two other vocalists, at least made the performance more interesting. In particular, the live toms and sub bass made for a physical experience. SKI, a duo built around Polish drummer Damian Kowalski, explored free rhythm more explicitly, without the references to folk music. No metronome, no click, no grid, just pure fluid rhythm. OPLA, another duo consisting of drummer Hubert Zemler and guitarist Piotr Bukowski, reinterpreted traditional Polish dances, such as the oberek, rooting their futuristic music in rural Polish culture and history. Zemler played one of those MIDI pads you can hit with actual drumsticks, while Bukowski processed his playing with various effects.

Ale Hop (courtesy of Unsound)

Ale Hop & Laura Robles, two Peruvian artists now based in Berlin, presented an hour-long exploration of their own transformation of traditional rhythms, drawing upon patterns from Peru’s central coast which anchored the more unstructured guitar noise. Hop would occasionally hammer her guitar on her slap with small mallets, and other times just let the guitar rip in a wail of drone, always grounded by Robles hand percussion, in a number of discrete movements or compositions or improvisations, at least of which was drawn from their recent debut record for Buh, Agua Dulce [Sweet Water]. And while the South Americans had to make the customary gesture towards fusion and tradition, they also undercut this narrative admirably; as Robles explained, “how traditional can this music really be since we are women and we live in Berlin now.” They take what they want but they very much are doing something new, and the interplay between the live percussion and electronic elements kept things interesting. At the start of their set, everyone in the crowd was seated on the floor. At the end, everyone was on their feet.

Japanese duo KAKUHAN performed at the Manggha museum accompanied by Polish drummer Adam Golebiewski. While KAKUHAN debuted only last year, their members have been at it for a while. One of them was controlling a DJ Mixer plugged into an Elektron and some effects, while the other played cello and pedals. We got a slow build up of cello drone and noise, evolving into skittering beats not miles away from the work of Speaker Music. After 30 minutes, Gotebiewski came out, but rather than lay down some beats of his own, he channeled free percussion improvisation, scrapping cymbals and such. There’s an organic quality to the pacing and development of this music, and it does veer into contemplative psychedelic territory much more than body moving beats, always with an eye on the future.

Even Ben Frost, at his performance at ICE, was supported by guitarist Greg Kubacki. We’d heard through the grapevine that there had been some technical difficulties in preparing the show, but I had understood they might be related to Tarik Barri’s visuals. Perhaps the problem was with Frost, who apologized when he walked on stage, and gestured angrily at his laptop several times throughout their set. “That’s live electronic music, folks!” he cried half-jokingly once when his laptop seemingly shut off. But at the same time, his contribution to the music was in the form of powerful rhythmic bursts of sound followed by silence, so he could have easily just kept going and no one would have been the wiser. But it was clear he was frustrated, and Kubacki’s ability to continue playing despite Frost’s technical difficulties underscored that precarity that is more inherent to live electronic music, and perhaps helps explain why more artists are gravitating back towards more traditional instrumentation.

I also must mention Mabe Fratti, an experimental cellist and composer from Guatemala based in Mexico City, whose performance stands among the highlights of the festival. Her album Se Ve Desde Aquí [Seen From Here] was released around this time last year, and was partly conceived in Rotterdam’s WORM studios. Where her studio recordings lean towards the intimate, for Unsound, she was joined by I. La Católica, Hubert Zemler & Spóldzielnia Muzczna, a contemporary ensemble consisting mostly of brass instruments. The drums and guitar played an important role in the energy of her performance, and I’m always a sucker for beautiful brass arrangements, but Fratti’s manipulated cello playing and vocals could surely carry these songs on their own. Fratti’s voice is plaintive and thin, yet sensuous, perhaps akin to Blonde Redhead’s Kazu Makino.

Polish artist Martyna Basta and the now LA-based claire rousay both developed idiosyncratic and “diaristic” approaches to composition during the pandemic, what rousay has (half-jokingly?) been calling Emo Ambient. As is often the case with the best collaborations, their set was not merely a successful fusion of their styles but resulted in something new. Basta played guitar and manipulated her voice, while rousay seemed to be triggering and manipulating small percussive sounds, the kind of ASMR rustling we could expect. There were also some field recordings, and rousay eventually rotated to add some notes from an upright piano. Even when playing guitar or piano, however, there seemed to be little correlation between their gestures and the sound we heard, which is fine by me. Gesture can be important, but I think it is also overrated. I’m all for acousmatic sound, where the origin of the sound is beside the point. I think that’s where the diaristic ambient tag falls short. Like experimental, diaristic refers to the method of production, not the aesthetic or the sound itself.

So ultimately the eight days of DADA were full of references to the historic avant-gardes and contemporary investigations of AI and big data, occasionally some combination of the two. For other performers the relation to the theme was more oblique (or non-existent), but the general sense of absurd delirium did a lot to lighten the mood and provide some much needed levity. The shorter performances peppered throughout the festival did a lot to change the rhythm of the festival, and this too was a welcome innovation. A general sense of weird affects also permeated so much of the work, especially the visuals, and this seemed to be more a reflection of current aesthetic interests rather than explicit references to dada. And then of course we’re living amidst war and (post) pandemic trauma, which gives our contemporary moment a bit of added resonance with the spirit of dada. Perhaps it’s no surprise, then, how many artists’ works revolve around the voice, as semantic bearer but also, even when artificial, as bearer of humanity.

Lastly, it’s always a big deal for us to be able to cover festivals like this, let alone come to Europe from North America to do so. Thanks once again to Unsound and Modern Matters for hooking me up with press credentials. And thanks to those of you who subscribed and read my delirious daily reports. And if you are closer to NYC than Krakow, don’t forget Unsound has some free concerts planned with Moor Mother and the Caretaker at Lincoln Center this December!

- Unsound

- Unsound

- Unsound

- Unsound

- Unsound

- Unsound