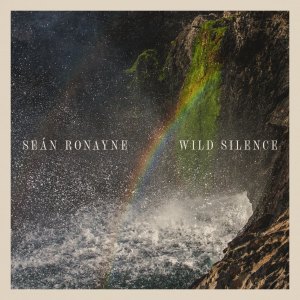

Very few field recording albums cross over into the mainstream, attracting the public’s eye. The last to make an impact was Australian Bird Calls – Songs of Disappearance, which topped the overall charts in its native land and spawned a series of sequels. The next looks to be Seán Ronayne‘s Wild Silence, which swiftly rose to the top of Bandcamp’s Field Recording chart, was prefaced by TV appearances and is being sponsored by Irish Wildlife Sounds.

Very few field recording albums cross over into the mainstream, attracting the public’s eye. The last to make an impact was Australian Bird Calls – Songs of Disappearance, which topped the overall charts in its native land and spawned a series of sequels. The next looks to be Seán Ronayne‘s Wild Silence, which swiftly rose to the top of Bandcamp’s Field Recording chart, was prefaced by TV appearances and is being sponsored by Irish Wildlife Sounds.

Wild Silence is also a very long album, thirteen tracks topping out at three hours, nine minutes. The average piece is exactly fifteen minutes. Ronayne writes, it may be used “for use as a sleep aid, a mediation aid, a stress-buster, a study/work companion, or to just bring some joy to your ears,” but it’s much more than that; the album s a fundraiser for Birdwatch Ireland and a reminder of our fragile ecosystems. Due to its internal diversity, Wild Silence also makes a fine entry into the wide world of field recordings and soundscapes for those who may have been resistant, or even unaware of the offerings.

How best to listen? If one is able to set aside a three-hour block at home or at work, the effect is sublime, a tour for the mind. But the valid temptation is to crank the volume until it reaches real-life levels, so that one feels immersed in these sonic environments. “Summer on the Bog,” which introduces the local dawn chorus, is a fine introduction, and those with keen ears may recognize the sounds of birds that are absent from their own native environments. The loudest pieces, sea-facing and serendipitous, capture cacophonies of natural sound. “Murmuration” is the first, an astonishing piece that sounds like the roar of the sea but is in fact the simultaneous flapping of thousands of starling wings. Many have seen murmurations, but few have ever heard them like this. The same holds true for the Kittiwakes of “Skellig Greeters,” making a site-specific racket, grounding the album in geography. And who can resist the “grunting fish” of Ballycotton Pier, which can only be heard underwater?

In “Iceland to Ireland,” a flock of Whooper Swans complete their 1400 kilometer journey in a loud thunderstorm, finally safe and sound: a field recording that captures not only a set of sounds, but a story. While listening, it’s easy to anthropomorphize the swans, hearing relief in their cries as well as humorous retellings of the journey. In like fashion, one hears alarm in the cries of those caught in a “Wild Atlantic Storm,” which rages violently with no end in sight. Ronayne thinks the herring gulls are laughing; we’re not so sure.

By the end of the set, Ronayne turns serious, although one can only intuit such a turn in the titles and liner notes. “Extinction – Here and Now!” contains the calls of what may be the last living pair of Irish Ring Ouzels, whose sounds once dotted the entire landscape. “What have we done?” writes Ronayne. “Where will it end?” The piece becomes part of history, a last effort at preservation. The artist concludes with “A Personal Solace,” returning to the ocean spot that consoled him as a child, careful not to reveal its location, preserving its pristine anonymity. For him, there is at least one spot left. The challenge, subtly implied, is to preserve such spots not only for ourselves, but for their original inhabitants. (Richard Allen)