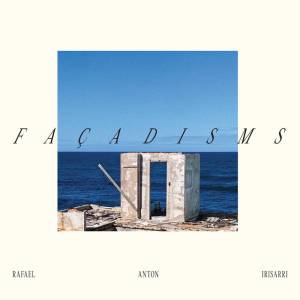

A week prior to headlining the Ametric Festival in Crete (September 12-14), and only days after the announcement of his upcoming November album FAÇADISMS, Rafael Anton Irisarri spent some time conversing with our own Greek correspondent Maria Papadomanolaki. In this interview, the artist looks back over his career, discusses the process of making music, highlights the benefits of collaboration, and discusses the challenges of today’s music industry. After reading, be sure to pre-order the new album, upcoming on Irisarri’s own Black Knoll!

A week prior to headlining the Ametric Festival in Crete (September 12-14), and only days after the announcement of his upcoming November album FAÇADISMS, Rafael Anton Irisarri spent some time conversing with our own Greek correspondent Maria Papadomanolaki. In this interview, the artist looks back over his career, discusses the process of making music, highlights the benefits of collaboration, and discusses the challenges of today’s music industry. After reading, be sure to pre-order the new album, upcoming on Irisarri’s own Black Knoll!

What was the starting point for you in this career of many years? What started it all?

I’m a self-taught musician who grew up in the 80s and 90s, learning guitar and bass by playing along to records. Coming from a working-class family, most of my music came from hand-me-downs, starting with heavy metal cassettes in my early years. My musical horizons expanded when my uncle introduced me to Reggae and Dub music, and at fifteen, a friend from the industrial scene introduced me to ambient electronic music via The Orb. Afterward, I explored everything from The Cure, Joy Division, and Kraftwerk to My Bloody Valentine, Cocteau Twins, Harold Budd, Talk Talk, and Slowdive. After moving to Seattle in the 2000s, I became involved in the thriving electronic music community there, organizing and often running sound for shows, which sparked my interest in audio engineering. Working behind the FOH console led me to the studio, where I got my start polishing home recordings by artist friends. I spent countless hours studying and training in studios, and soon, more artists (and labels) sought my engineering skills. This eventually led me to set up a professional mastering studio at my home in Seattle. It was a dark, hillside room with little sunlight, so we named it Black Knoll. In 2008, I got signed to Ghostly International, releasing my debut album as The Sight Below. Since then, I’ve lent a hand to countless Ghostly releases: Julie Byrne, Hana Vu, Helios, Telefon Tel Aviv, Galcher Lustwerk, Steve Hauschildt, Lusine, and so many more.

In what ways has the move from Seattle to Upstate NY influenced the way you listen, think, and make music?

I moved to New York over a decade ago. During that move, everything in my studio, and all my possessions were stolen. It was a devastating and incredibly stressful time, to say the least. Thanks to the kindness of strangers, friends, listeners, and the incredible support of the Ghostly International family, I was able to rebuild the studio in 2015. I am so incredibly grateful to them, they are truly wonderful people. After the rebuild, the studio client base grew significantly, and I was working with so many great labels like Temporary Residence, Dead Oceans, Felte, Umor Rex, A Strangely Isolated Place, and of course Ghostly, to name a few. In recent years, I’ve been working with more genre-spanning independent artists (particularly in this post-streaming music landscape), podcasts, and art house film projects from all over the world. This in turn has perhaps broadened my way of listening, thinking, and making music. I’ve gotten to work with some of my musical heroes, and done many incredible collaborations as a result of my relocation and it being more central. I can drive into the city, or out to the airport and meet visiting musicians. I’ve also found new ways of creating, as being a bit isolated living in the woods has focused a lot on my creative process. Fewer distractions is a positive thing.

How important is improvising in the way that you work?

Improvisation is an essential part of how I make music. My new album, FAÇADISMS, is influenced by my interest in brutalist architecture. Reading about brutalism’s emphasis on raw, unrefined aesthetics and its innovative use of materials provided me with new perspectives on structure and form for my compositions. This inspiration led me to approach the album with a focus on creating a rawness that mirrored the brutalist ethos—where imperfections and bold, structural elements contribute to the overall artistic statement. I devoted countless hours to improvisation. I record everything in real time. This process allowed me to capture many spontaneous ideas and unexpected moments that often yielded compelling motifs that would become integral to the album. Once the improvisations were recorded, I shifted to editing them. I reviewed hours of these improvised recordings to find melodic motifs and sections that stood out. These would go on to become the building blocks for the compositions. I expanded on these motifs by adding layers of instrumentation and meticulously mapped MIDI to integrate various parts into the music. For this album, I forwent using a click track and instead chose to rely on my internal sense of tempo to achieve a more fluid sense of time (in contrast to the overly quantized,gridded approach of modern music production). This methodology produced a sonic palette that feels organic and harks back to the unrefined aesthetic of brutalist architecture. Of course, this can be very impractical when you are also working with sequencers because I spent many hours mapping MIDI notes and tempos on tracks so I could sync synthesizers to my guitar playing, and vice versa.

Does your work as a mastering engineer differ from your work as a musician?

Yes, I’d say so. I view mastering as a system of checks and balances. My aim as a mastering engineer is to listen and align myself with the essence of the music, preserving that while enhancing and enriching the sound to create the best version of the artist’s vision. My approach is rooted in the respect that I have for the artists, the aesthetics I believe in, and the craft itself. It’s crucial for me to connect with the music I’m working on. I’m highly selective about the projects I take on. I only work on music that I genuinely enjoy. It’s impossible to do a great job if you don’t truly connect with what you’re hearing. Resonating with the artist’s vision and aesthetics is essential. Something magical occurs when our creative values align. Although mastering is primarily a technical trade, there have been many times when my production sensibilities have contributed to enhancing a recording. Mastering audio is like flying an airplane—experience and knowledge are key. While nice analog gear helps, it’s worthless unless you put in the hours needed to use it effectively. In contrast, my work as an artist is purely creative. I get to create and play with the happy accidents that occur during improvisation in the studio and shape those beautiful moments into compositions.

Are these two aspects of your practice separate or independent?

I try as much as possible to compartmentalize my creative process to maintain focus and clarity. Often, when I’m writing, I deliberately set aside technical concerns to concentrate on the aesthetics, mood, or emotional impact of a piece of music. This approach requires a certain level of discipline, as it involves resisting the urge to get bogged down in technical details—such as obsessively tweaking EQ settings—when the priority should be on shaping the arrangement and overall vibe. Ensuring that the technical aspects don’t overshadow the creative allows the project to bloom.

You have recently released a wonderful collaborative album with Abul Mogard and a new Orcas album with your longtime collaborator Benoît Pioulard. What is the most inspiring aspect of collaborating with another artist?

Collaborating is so inspiring and important to me. I genuinely cherish and appreciate working with other artists. It is so refreshing when our values and aesthetics align. Beautiful friendships have formed as a result of these moments of collaboration. For example, my work with Benoît Pioulard has been enriched by years of friendship and shared experiences, because it adds so many layers of meaning to what we create together. With Abul Mogard, our collaboration came from a mutual respect and admiration that we had for each other. Last year, when an original commitment with another artist fell through, having Abul step in for a live show in Madrid was a blessing. Not only did it save the day, but I also discovered how naturally we connect musically. I appreciate him very much and really enjoy the seamless flow of our performances together. We have incredibly similar ways of working in the studio too. It is rare to find a kindred spirit later in life, and so I value it greatly. My friend James Brown is a UK producer who worked on the latest Orcas album. He has been a significant mentor to me. James embodies the spirit of the classic era of music production where an entire team collaborated on an album from producers, and recording engineers, to mixing engineers, and more. This sense of collective effort has somewhat faded in the 21st century, particularly in electronic music, where the producer often assumes multiple roles: composer, engineer, and arranger. While this approach can be effective, it can also lead to a loss of the rich, multi-faceted input that teamwork provides.‘FAÇADISMS’ is a testament to the value of collaboration. I crafted the album with a specific vision, before sharing it with James. His feedback was incredibly insightful, and he offered fresh perspectives and valuable suggestions that I was keen to explore. I refer to this approach as ‘Strategies (against conformity),’ which is how I credited James on my latest album. His contributions exemplify the creative magic found when combining different viewpoints and expertise, especially from someone whom you greatly respect and admire.

Collaborating is so inspiring and important to me. I genuinely cherish and appreciate working with other artists. It is so refreshing when our values and aesthetics align. Beautiful friendships have formed as a result of these moments of collaboration. For example, my work with Benoît Pioulard has been enriched by years of friendship and shared experiences, because it adds so many layers of meaning to what we create together. With Abul Mogard, our collaboration came from a mutual respect and admiration that we had for each other. Last year, when an original commitment with another artist fell through, having Abul step in for a live show in Madrid was a blessing. Not only did it save the day, but I also discovered how naturally we connect musically. I appreciate him very much and really enjoy the seamless flow of our performances together. We have incredibly similar ways of working in the studio too. It is rare to find a kindred spirit later in life, and so I value it greatly. My friend James Brown is a UK producer who worked on the latest Orcas album. He has been a significant mentor to me. James embodies the spirit of the classic era of music production where an entire team collaborated on an album from producers, and recording engineers, to mixing engineers, and more. This sense of collective effort has somewhat faded in the 21st century, particularly in electronic music, where the producer often assumes multiple roles: composer, engineer, and arranger. While this approach can be effective, it can also lead to a loss of the rich, multi-faceted input that teamwork provides.‘FAÇADISMS’ is a testament to the value of collaboration. I crafted the album with a specific vision, before sharing it with James. His feedback was incredibly insightful, and he offered fresh perspectives and valuable suggestions that I was keen to explore. I refer to this approach as ‘Strategies (against conformity),’ which is how I credited James on my latest album. His contributions exemplify the creative magic found when combining different viewpoints and expertise, especially from someone whom you greatly respect and admire.

As an artist, curator and mastering engineer, how do you navigate the challenges and the unnecessary noise and clutter of today’s music industry?

It is certainly polluted, innit? Today’s digital landscape is increasingly polluted, and discovering good quality new music often feels akin to being a prospector sifting through a riverbed for gold. Each new gem you uncover—whether through algorithms or personal exploration—seems hard-won after enduring a pile of shit. Social media, in particular, can feel like a cesspool of ideas that is overflowing with a mix of the insightful and the superficial. Social media makes the search for genuine, resonant artistry all the more challenging. Searching requires patience and discernment, as you navigate through an overwhelming sea of noise to find those rare moments of brilliance that truly stand out. I consciously decided a while ago to not contribute to this problem.

Releasing on vinyl has always seemed like a big (ethical) undertaking to me. What does releasing on vinyl mean to you?

Releasing music on vinyl is about creating a physical memento and a kind of document. Tangible and tactile. It’s something you can hold in your hands. The ritual of playing a vinyl record brings a unique warmth to the music and offers a nostalgic and physical satisfaction that digital formats can’t emulate. It’s a way to honor the music as an art form, giving it a lasting, tactile presence that enriches the listener’s experience. When listening to a vinyl record, you are focused on the experience – unlike listening to music on your phone, for example. Regarding the ethics of releasing on vinyl: many studies suggest that the environmental impact of streaming music can surpass the plastic waste generated by CDs and vinyl records, particularly when the energy used in streaming is non-renewable. Streaming music involves substantial energy consumption—from data centers to our personal devices—which contributes significantly to carbon emissions. This environmental cost starkly contrasts with the minuscule fractions of a cent that streaming services pay artists. The massive volume of data transmitted and processed for streaming, coupled with the minimal revenue artists receive, underscores a troubling imbalance. It’s alarming that the energy required for streaming often translates into negligible earnings for most musicians. Despite growing awareness, this remains a prevalent issue in the music industry that we have largely allowed to persist. The challenge now is to find sustainable alternatives and advocate for systemic changes that address both environmental responsibility and fair artist compensation. Recognizing the environmental impact of producing vinyl records, I am committed to releasing all my music on BioVinyl through my label. This innovative technology replaces petroleum-based PVC with recycled biomaterials, such as used cooking oil, resulting in an LP that is 100% recyclable and reusable in the circular economy. While this step is small in the context of the broader effort toward environmental sustainability in the music industry, it marks a significant move in the right direction. Although the technology is still emerging, I am hopeful that it will become the standard as more labels and artists seek out these eco-friendly practices.

What can we expect in the near future from your recently launched Black Knoll Editions label?

Earlier this year, I made a significant shift in my musical career by launching Black Knoll Editions. This move was driven by a desire to take greater control over my creative and operational processes. After years of having my music scattered among, and often exploited by, various labels, I realized the need for a central hub where my entire body of work could be curated and developed in a way that truly reflects my artistic vision. To be candid with you Maria, I became disillusioned with the problematic practices of many labels I had worked with in the past, including some people I considered close friends and mentors I held in high regard. I began to question why some of these labels still take up to 50% of an artist’s income long after a release had recouped – basically, half your income in perpetuity. What value are they providing to justify such a significant cut? Additionally, I’ve released my music on labels that were not only inefficient or incompetent with accounting and marketing, but also outright greedy. Some labels prioritize their profits over the welfare of their artists. For instance, some labels won’t even sell their own artists’ records back to them so that the artists can sell them to their fans on their Bandcamp pages (which is similar to selling records on tour). Some labels will humiliate the artists when they rightfully request their masters back. These unethical practices, including the quickness with which some labels drop artists at the first sign of decreased returns, demonstrate a lack of respect for long-term relationships, artistic contributions, and overall human decency. Such attitudes were incredibly disheartening and made me question whether I wanted to continue releasing music at all or if it was time to quit and pursue something else entirely. After a lot of heartbreak and much reflection, it motivated me to take control and build my own thing. I’d like to manage not only my music but eventually the music of other artists, fairly and ethically. This new direction feels like a natural evolution in my artistic journey that allows me to shape the future of what I do more deliberately. My current focus with Black Knoll Editions is to both release new projects and reissue my long out-of-print albums on BioVinyl. I want to offer a fresh perspective on past works while pushing forward creatively. I’m incredibly grateful to be working with a fantastic team of people, including my distributor Morr Music, the talented Daniel Castrejón (of Umor Rex label) who handles all the beautiful design work, and Karen Vogt, who manages press relations.

Should we expect a comeback from The Sight Below?

I’ve been wanting to create new material as The Sight Below, but I’ve been holding back and waiting for the right emotional space. More importantly, I’ve been waiting for a sound that truly captures the essence of this era. It feels more important to do this, especially in light of the incredibly talented, and younger artists around who have been inspired by my earlier works and are already making exceptional music (Rachika Nayar, Geotic, etc). I want to put forward a sound that resonates in today’s shifting musical landscape. Maybe it’s a kind of writer’s block, but to me, it’s about avoiding the easy route and resisting the urge to revisit what I’ve already done. I’m not interested in rehashing old ideas or sounds that worked in the past. The real challenge is to evolve, to find a fresh direction that pushes boundaries, and to bring something unexpected and meaningful to the table. I’ve spent countless hours in my studio recording sketches and ideas—there’s easily enough material for a double LP. I can feel myself holding out for that moment of clarity. I imagine a breakthrough where everything falls into place and a cohesive sound emerges that distills the essence of The Sight Below in a new way. For me, creating music under this moniker has always reflected where I am at a specific moment in time. Right now, that means searching for the spark that compels me to take risks and push into new territory. I believe that once I find that new direction, the music that emerges will be far more rewarding—not just for me as an artist, but for the listeners too. It’s a long and arduous process of waiting, listening, and allowing something genuine to take shape. Looking back, my debut LP Glider was born from my love of shoegaze and space rock. This album was heavily inspired by bands like Seefeel and Windy & Carl. I created Glider during a transitional period in my life when I had lost my day job and was destitute. Despite the stress of being utterly broke, it was liberating to have the freedom to write all day. I’d lock myself in the studio for days on end with just a guitar, a few effects, and a drum machine as my click track. Before starting the project, I had been experimenting with techno, but all my dance tracks were terrible—total rubbish. I had been sending demos to Ghostly International for years, and while they always responded politely with, ‘This is alright, but not for us,’ nothing clicked. Then one night, I recorded ‘Life’s Fading Light’ and sent it over. Sam, the label owner, immediately responded with, ‘This is amazing, we want to hear more of this!’ So, I stayed up for days writing and recording until Glider was finished. That experience taught me that sometimes you have to wait for the right moment and the right sound to emerge, and that’s what I’m doing now—patiently waiting.

I’ve been wanting to create new material as The Sight Below, but I’ve been holding back and waiting for the right emotional space. More importantly, I’ve been waiting for a sound that truly captures the essence of this era. It feels more important to do this, especially in light of the incredibly talented, and younger artists around who have been inspired by my earlier works and are already making exceptional music (Rachika Nayar, Geotic, etc). I want to put forward a sound that resonates in today’s shifting musical landscape. Maybe it’s a kind of writer’s block, but to me, it’s about avoiding the easy route and resisting the urge to revisit what I’ve already done. I’m not interested in rehashing old ideas or sounds that worked in the past. The real challenge is to evolve, to find a fresh direction that pushes boundaries, and to bring something unexpected and meaningful to the table. I’ve spent countless hours in my studio recording sketches and ideas—there’s easily enough material for a double LP. I can feel myself holding out for that moment of clarity. I imagine a breakthrough where everything falls into place and a cohesive sound emerges that distills the essence of The Sight Below in a new way. For me, creating music under this moniker has always reflected where I am at a specific moment in time. Right now, that means searching for the spark that compels me to take risks and push into new territory. I believe that once I find that new direction, the music that emerges will be far more rewarding—not just for me as an artist, but for the listeners too. It’s a long and arduous process of waiting, listening, and allowing something genuine to take shape. Looking back, my debut LP Glider was born from my love of shoegaze and space rock. This album was heavily inspired by bands like Seefeel and Windy & Carl. I created Glider during a transitional period in my life when I had lost my day job and was destitute. Despite the stress of being utterly broke, it was liberating to have the freedom to write all day. I’d lock myself in the studio for days on end with just a guitar, a few effects, and a drum machine as my click track. Before starting the project, I had been experimenting with techno, but all my dance tracks were terrible—total rubbish. I had been sending demos to Ghostly International for years, and while they always responded politely with, ‘This is alright, but not for us,’ nothing clicked. Then one night, I recorded ‘Life’s Fading Light’ and sent it over. Sam, the label owner, immediately responded with, ‘This is amazing, we want to hear more of this!’ So, I stayed up for days writing and recording until Glider was finished. That experience taught me that sometimes you have to wait for the right moment and the right sound to emerge, and that’s what I’m doing now—patiently waiting.

A Closer Listen thanks Rafael Anton Irisarri for his time and music! Be sure to check out the new album FAÇADISMS, released on November 8; pre-order link below!