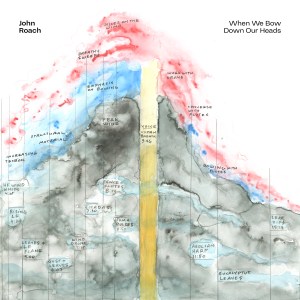

The wind whistles further into the spotlight as the climate continues to change. One of our top releases of 2025 was Grand River’s Chasing the Wind; late-year literary hits included Simon Winchester’s The Breath of the Gods: The History and Future of the Wind and Sarah Hall’s playful novel Helm. John Roach‘s When We Bow Down Our Heads pairs well with all of these, and is suitable for long winter nights during which the wind whips and howls and dances outside.

The wind whistles further into the spotlight as the climate continues to change. One of our top releases of 2025 was Grand River’s Chasing the Wind; late-year literary hits included Simon Winchester’s The Breath of the Gods: The History and Future of the Wind and Sarah Hall’s playful novel Helm. John Roach‘s When We Bow Down Our Heads pairs well with all of these, and is suitable for long winter nights during which the wind whips and howls and dances outside.

The wind is first the sound, and then the story. As the album begins, one hears the effects of the wind as it blows over water and against metal, creating its own musical currents and notes. Culled from an amazing decade of wind recordings, the project travels from fourteen spots in the United States to Mabul Island in Borneo and Kefalonia in Greece. As one cannot tell which wind is which, the soundscape turns into a mixtape of global winds, which themselves mix and mingle and cannot be separated.

Geophysical Scientist Joonsuk Kang is the first of three narrators who offer structure to the sounds. Kang takes the direct approach, explaining the fundamentals of wind, as if to a child. All around him the wind teases and whips, eventually drowning his words. By the seventh minute, the wind has reached gale strength, operating as a musical drone. “Who has seen the wind?” asks Christina Rossetti, from whose poem the album takes its title. Illustrator and storyteller Lauren Redniss calls the wind “the music of the weather,” and as she speaks, one can hear the improvised flutes of the natural “wind section” as the elements literally play their part. Are the wind chimes for us to hear the wind, or for the wind to play? It all depends on how much agency is given to the weather.

Other humans join the fray: double bassist Wolf Stratmann and mezzo soprano Inbal Hever. As they enter, one recalls that we have breath, and that the human voice is a tiny breeze, dreaming it is a gale. These performers duet with the wind, partners in its orchestra. The extended wordless middle is reminiscent of Andrzej Pietrewicz, snippets of voice snagged on branches, notes wafting in the breeze, car horns, alarms and sirens shocking the listener back to reality. And then real life comes rushing in; interdisciplinary artist and composer Raven Chacon speaks of wind in relation to borders. “Wind is not going to stop at a wall,” says Chacon, describing a temporary installation containing balloons that traced the routes of refugees prior to the U.S.-Mexico border wall. This serious injection deepens the impact of the entire project; as one hears the sounds of children, one begins to think of the wind as socio-political metaphor, most obviously the winds of change; and hopes that the wind that has blown one way might soon change directions, foiling politicians, restoring a natural balance. (Richard Allen)