For the current episode of Ukrainian Field Notes we traveled directly to Ukraine at the end of May, finally meeting a number of artists in person in Lviv, Kyiv and Ivano-Frankvisk.

For the current episode of Ukrainian Field Notes we traveled directly to Ukraine at the end of May, finally meeting a number of artists in person in Lviv, Kyiv and Ivano-Frankvisk.

In Kyiv we got to chat with Clemens Poole about fundraising and drones for drones, while Alla Zahayevich shed a light on the Ukrainian contemporary music scene and Andrii Barmalii described the production process of his debut album autopotrack.

To round up our interviews we also talk to Jordan Dykstra about his score for 20 Days in Mariupol and The Lazy Jesus about the follow up to his album UA Tribal.

We also look at a bunch of new releases by Incorrect Waves, Slavik Dzyga, Soundots, ummsbiaus & Difference Machine, ногируки, Whaler, некрохолод, 58918012, Maxim Kolomiiets and Ross Khmil, Anthony Junkoid and Andrii Strakhov.

We also look at a bunch of new releases by Incorrect Waves, Slavik Dzyga, Soundots, ummsbiaus & Difference Machine, ногируки, Whaler, некрохолод, 58918012, Maxim Kolomiiets and Ross Khmil, Anthony Junkoid and Andrii Strakhov.

But to begin with our monthly podcast for Resonance FM features a conversation with Clasps and lostlojic about mobilisations and their feeling about musicians who left the country.

Following our podcast is our Spotify Playlist for the month of June comprising this month’s interviewees selections and latest releases. Also included in our Spotify playlist is the track “A Version” by DJ Superlite and Arthur Snitkus from the fundraising compilation SESTRO out on система system. Snitkus, a musician and stylist, representative of the queer community, died while performing a combat mission in the Donetsk region. He was 36 years old.

MAY 21, 2024 – KYIV

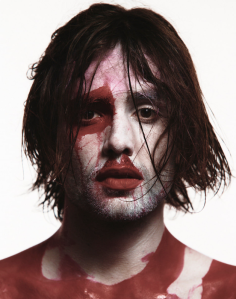

photo: Mariia Sosnovska

I am an artist from the US who has been living in Ukraine since 2019, and working here on different projects since 2014 and I run a noise label called Kyivpastrans.

I guess the most relevant project we currently have with the label is Drones for Drones where we issue cassette releases that are compilations of drones tracks by international and local artists and we work with a volunteering group called Fallout Noise to buy drones usually for musicians who are serving.

With the first Drones for Drones cassette, I think we raised a thousand dollars. It was a small project. It’s been growing now, but with the first one we bought drones that got sent to some of the guys from Module in Dnipro. I am now working on the third volume, which I need to release soon, but the project has been growing.

We also organise parties with different venues in Kyiv focused around noise and drone music. I usually work with a space called Ceramic Beats that’s in Podil [a district in Kyiv]. The guys from there are also involved in a project called Pererva Studio, but I have also done stuff with, for example, Abo records in the Kudriavska factory space. Yeah, it’s a pretty busy time for noise and drone music in Kyiv.

If I am not mistaken your background is more into the visual arts?

I can say that my professional background is more in the visual arts in terms of what my education is. I actually did my bachelor’s degree starting when I was 27, but everything I did before I studied art at the Cooper Union in New York was pretty focused on music.

I have played in bands since I was 14, or something like that. When I was a kid we organised punk shows and that kind of thing. Then I got into metal bands and did a bunch of acoustic stuff for some years and organised a bunch of DIY tours across the US.

I can say that my professional background is more in the visual arts in terms of what my education is. I actually did my bachelor’s degree starting when I was 27, but everything I did before I studied art at the Cooper Union in New York was pretty focused on music.

I have played in bands since I was 14, or something like that. When I was a kid we organised punk shows and that kind of thing. Then I got into metal bands and did a bunch of acoustic stuff for some years and organised a bunch of DIY tours across the US.

So, basically, a lot of my 20s was spent focussing on music but not in what I can call a professional way, more in a punk rock underground way where you were just doing it because that’s what you liked to do. You don’t make any money, you just run yourself ragged, pushing out albums that nobody buys and doing shows that sometimes people go to, but you know…

I think of that as the “Myspace era of DIY shows”. We used to do this thing where we would search a location for bands on Myspace and just message them saying, “Hey, we need to stop for gas in your town, can we play a show at your house?” And we would play shows and organize whole tours that way.

But yeah, I can’t say that I have a professional background in music. What I can say is that I was pretty committed to the idea of experimental music for a long time before I started thinking about myself as an artist and curator. And when I started working in art more professionally there was often some kind of sound event, maybe even an interest in time based media, and also in performative applications for artistic practice, but the sound stuff only came together after the invasion, after I had been playing music and writing stuff in Ableton for some time…

You just mentioned the invasion. Did it make you rethink your attitude to sound and did it have an impact on your practice?

You just mentioned the invasion. Did it make you rethink your attitude to sound and did it have an impact on your practice?

Absolutely, the invasion changed how I was thinking about sound, but because my role in the Ukrainian art scene is a bit blurred – in part, I am an individual creator of different projects and I have an artistic idea and I make my stuff, – but I also end up in a curatorial capacity often, and so part of my interest in being here is observing people around me, and I can definitely say that there was this change in the way people think about sound. In my circles this manifested in an interest in noise becoming not mainstream, but more visible.

As for me personally, like for everyone else, I couldn’t listen to music for a month and a half, but then as I was driving supplies in to Western Ukraine I came back to listening to music by listening to heavy stuff, like metal, I was interested in this brutal music and more specifically I was connecting with Liturgy and and 70s prog and stuff like that.

It’s interesting to hear what people listened to when they came back to music because everybody has something and for me it was this technical brutal stuff, and that was before I started playing the stuff I am playing now, which I jokingly call “melodic death noise”, because it’s influenced by this metal of the 90s. I am also interested in tearing different things apart and I am not sure exactly what is going on, but it’s been fun. But the thing that really changed for me, and my personal theory as to why I started to push towards noise and more chaotic music was because after the invasion I put all my efforts into activists and humanitarian and other initiatives.

Aside from driving supplies in the first couple of months, I was also a co-founder of a journal for Ukrainian writers and artists called Soniakh Digest. We worked with the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw to launch it as a website and we published a series of articles that were anti-westplaining. The project is still going, I think they got a new grant, but I am not part of it any more, but I realised that all of my creative activities had been captured by the war, and that was the correct thing to do, to focus everything that you can do on pushing back on this imperial violence and trying to have your friends voices being heard.

I also co-curated an exhibition at PLATO Ostrava in the Czech Republic and, even if it wasn’t focused on works about the war, we talked about it in that context. Then, when I was back in Kyiv, especially in the fall of 2022, I started to do these noise jams with my friend Leo, who now lives in Vienna, and we decided to make a label to make our noise jams legitimate. This was right when the blackouts started to happen, and I realised there was this weird inversion of my productivity. When there was no power I would be hot spotting my phone on my laptop editing texts for Soniakh Digest, or whatever, doing very concerted activist processes where I was trying to make these Ukrainian perspectives be heard, really important in my mind, and then the power would come back on and I would be, “Oh, I can play guitar a little bit.” I was using these moments of having electricity for the most pointless shit and I was thinking, “Why are we going for this pointless noise, this unlistenable shit?” I mean, what Leo and I were doing was not unlistenable, but in a sort of theoretical sense, why was I engaged in something that was pure abstraction and not using this resource that people were fighting for to keep the power on? Why was I wasting the power by making this garbage noise? What the fuck was wrong with me?

This is a kind of criticism that is still floating around my head, but I started to think that this is maybe a reaction to everything that is going on, in the way the war captures all your creative expression. If you are a conceptual artist there is no shelter in your practice because you are working with the ideas that surround you and when something like the war happens, when an invasion happens, there is no escape from it. You can’t turn to your practice to process it any way that isn’t direct, that isn’t like, “This is a fucked up situation I need to work on it, I need to put all my energy to fight back against it.” Obviously I am not fighting in a literal sense, but a lot of people are. That’s a lot to process in itself, but if I stick with this theoretical ground, as a conceptual artist your practice is totally captured by this awful thing, and I think going to this abstract music was related to this one way to escape by making a total garbage album that nobody is going to pay you for, and you are never going to raise money from. It was one way to experience temporary freedom from this total capture of your life.

Obviously I thought a little bit about this supposed CIA agenda of promoting Abstract Expressionism during the cold war and about the kinds of ways that a Western vision of individualism is running parallel to it, as in, “Let’s make this abstract garbage noise,” and in some kind of way this felt theoretically coherent.

As I developed this thought over time, while we were making these albums, things changed. I stopped working for Soniakh Digest for example, and started to do other stuff, but then I found myself I guess calling the bluff of that assumption, “Ok, you are making these garbage noise albums, the reason you are doing it is because they are impossible to exploit for any other purpose, so the more abstract you make the shit you are doing, the more impossible it becomes for that to be exploited even by the needs of the war.”

And so then I think this idea of the Drones for Drones compilation series appeared as the kind of an answer to that. “Ok can you make noise albums that no-one is going to listen to, can you make a noise album that is expressly for raising money specifically to do this?” And then I reached out to a bunch of friends and more well known musicians, like Thor Harris who played in Swans or Mario [Miron] the guitarist from Liturgy, and I started to try and get guys with bigger names to give me their own tracks, and then local artists here, and it actually worked, and we started to make money with it. So it was sort of a full circle of how I was thinking about the utility of this abstract music, what it could be, how it could be applied in this context, and if it could be applied to this context. A lot of this stuff isn’t answered, but this was my thought process.

Over the first few months of the full-scale invasion, many electronic artists incorporated air raid sirens and other war sounds into their music. These sounds became ubiquitous and part of the acoustic vocabulary of every citizen. For instance, at the Venice Biennale, Open Group presented a piece called Repeat After Me in which they got refugees from the East of Ukraine sharing their experience of the sounds of war and reproducing various types of weapons. There were others who incorporated snippets of speeches from Zelenskiy or similar material, which is something many now cringe at. When does one reach the point where there is enough distance to create something that is not an immediate response to events happening on the ground but that could carry the same impact?

Over the first few months of the full-scale invasion, many electronic artists incorporated air raid sirens and other war sounds into their music. These sounds became ubiquitous and part of the acoustic vocabulary of every citizen. For instance, at the Venice Biennale, Open Group presented a piece called Repeat After Me in which they got refugees from the East of Ukraine sharing their experience of the sounds of war and reproducing various types of weapons. There were others who incorporated snippets of speeches from Zelenskiy or similar material, which is something many now cringe at. When does one reach the point where there is enough distance to create something that is not an immediate response to events happening on the ground but that could carry the same impact?

I cannot say when that point occurred or will occur, but I think it is important to see all the creative processes that are impacting the music scene and the experimental sound based art scene evolving and learning from itself. As for the sound of air raid sirens, I also used them in a piece a year and a half ago in Portugal called “This is a sound” [Isso é um son]. With that piece I was thinking about the significance of these sounds in a different context. There were a lot of people working on that at the time, so I think using the raw sound made sense because it was about contextualising it, and also showing to a foreign audience the significance of the change, the significance of the sound.

I think now we are more in a kind of a meta examination of that. In my live sets I no longer use the air raid siren, but I have now started to use clips of interviews with Delia Derbyshire were she is talking about growing up during the blitz and hearing the air raid siren and she talks specifically abou how, for her, the siren is the first electronic music. She then became this pioneering musician making these tape loop abstract compositions and she composed the theme for Doctor Who with the same kind of idea of how abstract sound can be morphed into something meaningful or, in her case, into this eerie kind of sci-fiction world. That’s why I started to use the Deliah Derbyshire audio as a loop in some of my live sets.

I cannot speak for anyone else, and maybe people hate it when I do this, I don’t know, but for me it’s interesting because you start with using a direct found sound, but then you move to thinking who else has been impacted by that found sound, and how else has that changed into another context, and what happened after that. In the case of Delia Derbyshire’s experience, the advent of the earliest electronic music follows this period of mechanised warfare where it really is different from anything anyone has seen. Air power, for instance, wasn’t something totally new, but it was still pretty new in the way it was applied, and so that led directly to this early electronic music, which Delia Derbyshire is part of.

I guess my thinking with that is that there’s a similar change going on here. In an entirely unfounded and non-scientifically way, I attribute this interest in noise to this new sensitivity that Ukrainian society has for sound. The data point that I find super interesting, and I have actually proposed projects about it, although I haven’t received funding for them, is that in the first six months of the war every person in Ukraine with a smartphone suddenly had an ambient field recording practice, because every person had a siren, or a generator, or the sound of air defence recorded on their phone. This is crazy, to have this change where the entire society becomes experimental, field recording, soundscape artists. Even if they didn’t know it, everybody did it, and that to me suggests that there’s been this real change.

In the case of Open Group, the reason why their piece at the Biennale is so powerful is because people in Ukraine know sound in a totally different way. This is attractive to a foreign audience because other people do not have this sensibility, and it’s almost like impossible to even imagine what it is like to have that information. This is super fascinating, and I cannot say it is something I have comprehensively explored, but it’s something I try to explore in my practice.

But why do you think then that there aren’t more field recording based works to have come out of Ukraine since the full-scale invasion? The only albums that I can think of are Difference Machine’s ніколи не змиряться [Will never reconcile] and Heinali’s Kyiv Eternal which are two very different works for that matter.

But why do you think then that there aren’t more field recording based works to have come out of Ukraine since the full-scale invasion? The only albums that I can think of are Difference Machine’s ніколи не змиряться [Will never reconcile] and Heinali’s Kyiv Eternal which are two very different works for that matter.

I know a lot of people who recorded field recordings, but I know what you mean. I feel there wasn’t one really coherent project that was set out to do that, and forgive me if somebody is out there who did it, I just don’t know, or I am forgetting, but I also remember that with Soniakh Digest we wanted to ask people to tell us their dreams and do an archive of dreams, and for whatever reason we weren’t able to make it happen, but I know that later the Centre for Urban History in Lviv did do this dream archive and they might also be good people to ask about field recordings because they are super good at this very organised academic approach, and they are also pretty open to experimental forms. But off the top of my head I cannot think of something, and it is kind of curious because I do think that this is a very interesting moment.

Last year, together with the guys from Machine Room, the modular synth community, we did apply for a grant that was basically about making an archive of these field recordings, but we didn’t get it. That’s not to say that our project was perfect and should have been selected, but I know that if we were thinking of it, and I always think that if I am thinking of something with the half of brain that I have, someone else out there must also be thinking of it, so…

Anyway, it’s a super interesting question and, for me personally, it seems like it could be related to that same question about the war’s capture of creative efforts. Like you said, to use a lot of that material now is cringe, or whatever, and I can see that these sounds are so quotidian that one even begins to question, “Is it relevant?” But, at the same time, when there are institutions like the Centre for Urban History that are so good with that kind of documentation… I mean, maybe that’s the thing, we are looking at the wrong thing, we are looking at the creative community to do this, but the creative community’s specialisation is actually the reinterpretation or the reframing of that data set, whereas an academic community might be the correct one to look to for the archiving of that data set, but I honestly don’t know.

Something else that has been happening is that musicians have started using traditional sounds and traditional singing. Is this a direction you are familiar with and that you find interesting?

Something else that has been happening is that musicians have started using traditional sounds and traditional singing. Is this a direction you are familiar with and that you find interesting?

I can think of the Hutsul sample pack that Gasoline did, and similar initiatives, and I definitely have this feeling that folk tradition inspired stuff is enjoying a new relevance. At the same time, I also have this feeling that this stuff was present before, and I don’t know if I specifically see a shift to that, but I am in no way a comprehensive expert in how different people are using sound in music and there’s stuff that happens in pop music that I am not that connected with, and not just pop music, lots of genres, that I am not super expert in. I remember that, when Gasoline did that Hutsul sample pack, I thought it was a pretty interesting project and the album they put out [Спадок] was kind of cool, and it expresses this, but to continue to chase this idea that I have about what’s going on, for me, this noise stuff is a more relevant direction rather than this traditional stuff. Maybe this is because of my musical background, as I used to do this more folksy stuff in the US and I am now not so into it, I am more into this abstract stuff.

Anecdotally, I can just say that when I started doing the Drones for Drones albums, a lot of the venues in Kyiv started messaging the Kyivpastrans instagram account and would be like, “Hey, maybe you wanna do a night, because we have the ‘hmtz hmtz shit’ already most nights of the week, but we really want to do something more experimental, we want to have a night that is weirder.” As someone who’s been living in Kyiv for several years, and working here for even longer, I witnessed the sort of total domination of techno in terms of what the clubs are all doing. When K41, the big club opened, I remember Podil was full of Germans, every person in Berlin I knew was like, “What the fuck are you doing here?“ And they all came for this opening of the big club, and techno was like king. Now, I don’t want to avoid this question about the integration of traditional music and stuff like that, but I think those dance music genres are absorbing some of that, and maybe it is more represented in that techno dance world, I don’t really know, but while this dance genre is still the number one thing, it seems to me that the clubs are saying, “We want to go to something that outside of this now.”

What’s interesting is that a lot of the noise and experimental musicians are into traditional instruments, like Oleksi Podat is often using a flute or an acoustic instrument in his live stuff, or like the guys I play with at Smalta, and all of that is something that was preexisting in this weird mash of experimental sound stuff. So, I guess… this is partially me arguing the thing I think about all the time, that the more noticeable change is this move towards a mainstream interest in further abstraction.

It may be totally true that in the more rigidly formal genres there is an incorporation of traditional music as a way to signal a support for Ukrainian culture, but in the experimental worlds I feel that an interest in that existed previously and has always been constant. I mean I think there’s lots of documented historical cases of folk revival especially when the nation and national identity are under threat, so I think it probably works in that same frame, but I don’t have any way to quantify it or claim that I know more than I do about it.

What is your take on the divide between those musicians who have left and those who stayed?

What is your take on the divide between those musicians who have left and those who stayed?

As a foreigner who operates here I really want to avoid making judgements, or even platforming judgments in my thinking about people who chose to leave and people who chose to stay. I have lots of friends who left, and lots of friends who stayed. I don’t think it’s up to me to think out loud about their decisions and the way that the community has perceived that.

I can say that I know a lot of people who came back because it was hard for them to work abroad and think through what was going on here. I can also say I was on the jury of Molodist Film Festival in October last year and we saw several films in the short film series that were about people who were abroad and they were missing home and alongside films made by people here and I can say that the audience definitely responded more favourably to work about being here. In terms of the films about “I really miss Kyiv” there was kind of this feeling, “Well…”

I don’t fault anyone for making the choices they need to take in order to make their lives work. I know people who joined the army, I know people who are worried about being mobilised, I know people who went abroad, I know people who went abroad illegally, and I feel that my role is to observe and to support, but I don’t have any kind feeling or thing I want to say to anybody about that. I want them to tell me what works for them, without having to tell them anything.

One of the questions I always ask is what are the misconceptions that people still hold about Ukraine two and a half years on from the full-scale invasion.

One of the questions I always ask is what are the misconceptions that people still hold about Ukraine two and a half years on from the full-scale invasion.

In all my work before this I was interested in thinking critically about Ukrainians’ perception of specifically the US, but the West in general, and I saw Maidan as a belief in a Europe that actually didn’t exist anymore. I think Ukrainians when they went to Maidan it was very legitimately against Yanukovych and Russian meddling, but part of that contained an idea of Europe that was a pre-financial crisis Europe, a Europe that was welcoming countries with problematic financial histories and situations, and I think that Europe died with the financial crisis. The Greek crisis and all of that made the EU into a different thing, so I was always interested in which EU Ukraine was perceiving. Was it the historical EU, or the EU in its current state, and the EU that is upset with Romania, Bulgaria for not getting rid of their financial problems? This was always super interesting to me.

I think now as I have mostly been living here it’s hard for me to understand how people perceive Ukraine from outside, and I don’t know what kind of misconceptions there currently are. I think more than misconceptions, people in the US, which is what I know best, are unable to hold multiple thoughts in their heads at once about what’s happening in the world, so it’s very hard for them with the current crisis in Palestine to even think about what’s happening here. That said, I am really frustrated by the way the US government has tried to equate these two wars and pretend that giving arms to Ukraine and giving arms to Israel are somehow the same thing, and I think the American political elite is strategically interested in convincing the American population that things can be simplified in this way. Personally, I don’t believe they can, and I think that it makes it so that I can’t even talk about misconceptions that Americans might have because I think they aren’t thinking about Ukraine anymore, I think it’s gone from their minds.

I guess in terms of my work in particular, the point of frustration has not been a misconception, but a struggle to get Americans, and I guess also people in Europe, to understand that some of their romantic ideas of what anti-fascist resistance can be are not really applicable in the full-scale war. I had a noise musician tell me that he only wanted to support projects that were anarchist non-state initiatives, and I was like, “I get you, like that’s cool, but the war has evolved. I understand that at the beginning you could have supported a territorial defence battalion that declared to be anarchist and that would have made sense, but the war has evolved. All the territorial defence was absorbed into the regular army, there aren’t roving bands of dudes who are out fighting the Russians. The front is part of a huge machine and those guys need help and that’s where our friends are, and that’s who we are supporting. It’s not about some idea of the State, it’s about the preservation of the society.”

I think the sort of fantasy of a more disorganised warfare has been an impediment to me getting people to donate and participate in the projects I am doing, because people don’t want to be basically donating to a regular army, they want to be donating to some special thing where you know the guy, and I have to say, “Well, you know, I do know the guy, but he’s in the army and he needs a drone so let’s get him a drone, and yes, I know you pay your taxes and it goes to the government and they send Ukraine weapons, but the guy still needs stuff and he’s my friend and we need to help him, and even when he’s not my friend, he’s a guy who knows a guy that I know, or it’s guys who run a club that I went to, guys who runs a record label, so…”

There have been an unprecedented number of fundraising compilations for Ukraine, compared to Palestine for instance, why do you think that is the case? It might be too simplistic, but do you think this could be because, since Maidan, Ukrainian civil society has had a healthy distrust of authority and has become accustomed to civic activism?

There have been an unprecedented number of fundraising compilations for Ukraine, compared to Palestine for instance, why do you think that is the case? It might be too simplistic, but do you think this could be because, since Maidan, Ukrainian civil society has had a healthy distrust of authority and has become accustomed to civic activism?

I mean I know this line of thinking and I heard people talk about it before it’s the same thing that makes people say, “If you go into a room with ten Ukrainians there’s ten hetmen,” or whatever these expressions are, but I don’t know. I didn’t came here til after Maidan. I know that especially in the first part of the war, a lot of people did attribute the way people joined this self-organised stuff as an extension of the community activism of Maidan, and there is a potential way to extend this into the cultural sphere with these online fundraisers, which is truly incredible, it’s like non stop, it’s like constant and it’s really inspiring and cool, this sphere culture like the aesthetics evolve and this I really interesting

I cannot say that I am any kind sociologist with enough expertise to say I could convincingly draw this line, but I would believe it if somebody told me that, it would make sense and I don’t know at all how to compare it to for example the Palestinian situation where… I mean, this is again, I really dislike the parallels that get made, even the parallels equating Ukraine with Israel, or equating Ukraine with Palestine, it’s bullshit both ways. What is happening here I understand partly because I am here, but I understand it also partly because there’s like a clarity to what’s happening. I do dislike the comparisons, but I don’t know what it’s like for Palestinians, I don’t know what make it so that they wouldn’t have as many fundraisers, I don’t even know if that’s actually true, I have no idea.

I have friends in the US who are doing different initiatives that are based on Palestinian solidarity and I don’t know anything about it so I can’t say. What I do know a little bit about is Ukraine and if you wanted to make the argument that there is this tendency in Ukrainian society to do these grassroots initiatives, I would believe that. I would say that seems reasonable. Having lived here, having worked with people here, having observed how creative processes happen, how fundraising happens, I would totally buy it, that’s a real feature of Ukrainian society.

MAY 22, 2024 – KYIV

Did the full-scale invasion change the way you perceive and you think about sound and has it had an impact on your musical practice?

There was, of course, a change. As the full-scale invasion happened, I stayed in Kyiv. In my district on the left bank of the Dnipro there are many lakes and one can normally hear a lot of natural sounds, but in March-April, it was impossible to go out and walk in nature. There was virtually total silence, there were almost no cars, the only noise came from the road going to Kharkiv, which was understandable as the military was going east in that direction.

In spite of that I decide to continue working as a composer, I was working on the soundtrack of a film about a historical figure of the XVIII century. Incidentally, the film was very well received, which was surprising for me, but the audience really enjoyed it. Anyway, the film production company called me to say we had to finish the film quickly as the war had started. I tried to find musicians that were still in Kyiv, like the violinist Ihor Zavhorodnii, Andrii Pavlov or Susanna Karpenko. We worked in the studio and I understood it was very difficult to work under such circumstances, as it was dangerous and some found it difficult to perform and play.

What everyone told me is that at the beginning of the invasion they weren’t even able to listen to music…

It wasn’t my case. I am a professor at the music academy and we were still working with my students every day in electroacoustic music. I also have a small ensemble and we just took a break for three weeks, but we continued working online. For me, to continue working was a way of building up courage and morale.

It wasn’t my case. I am a professor at the music academy and we were still working with my students every day in electroacoustic music. I also have a small ensemble and we just took a break for three weeks, but we continued working online. For me, to continue working was a way of building up courage and morale.

At the same time we also organised the evacuation of a number of students to Freiburg in Germany because I was working with the Erasmus programme and 45 students from different conservatories from Kharkiv, Odesa, and Kyiv now study in Freiburg. Our work in education continued in a intensive way.

The first project I worked on was with Georgiy Potopalskiy, aka Ujif_notfound. It was an electroacoustic piece for violin composed for Austrian radio called “Journey to the end of night”, like the novel by Celine. We recorded the violin with Andrii Pavlov. It became a very important experience because Pavlov didn’t want to play and this triggered an artistic and personal dialogue, “What can be done? What can we play? How can one play the violin in the midst of war?”

Did you find an answer to that last question?

For Georgiy, Andrii and myself the answer was to rediscover our practice. Andrii is one of our best musicians of classical music, but this was maybe the first time he got to improvise. And he produced a very rich sound with overtones and a slightly aggressive sound. When Georgiy and I heard it, we thought it was great. Andrii used the violin as a means to create a new sound in the midst of war, more aggressive than usual.

We didn’t fall into a depressive state without knowing what to do. Our was an energetic, objective and rational response, in a way.

There are many Ukrainian musicians, especially within the electronic scene, that use sounds of war… Like the air raid sirens?

Yes. And also tracks incorporating snippets of speeches from Zelenskyi. Yes, I heard many such works. It’s like radio art, or documentary radio. Amongst the first things I heard was a piece by a group from from Odesa with snippets from speeches against Russians and Putin. It’s a bit like agit-prop, like a sound postcard. For me it wasn’t something I was interested in.

But there’s a great piece by Andrii Barsov, “Still life” which begins in a very aggressive way with an air raid siren. It’s an artistic piece with a narrative, 10-15 minutes with the sounds of explosion. Potopalskiy was saying, “No, it’s not good to use the sound of sirens, it’s too direct,” but in this case it worked well for an international audience.

As these sounds can be triggering, does it raise ethical questions to use them?

We played this piece in Lviv at Radio Taras, and Ostap Manulyak interrupted the performance. I can understand the reaction, but this piece was actually intended for a concert in Paris.

How can one effectively transmit the war experience to someone who has no direct experience of it?

What we can transmit with music is that we are strong and have our own independent national culture. We are ready to continue our struggle against Soviet Russia ideology. This Russian narrative that Ukraine is part of the empire is wrong. We do exist. A good example of music with a message is Potopalskiy’s Hypogonadism, which is a syndrome that occurs when the body’s sex glands (gonads) produce little or no hormones. I am being flippant here, but to me it’s about remaining optimistic, and more masculine, and not being castrated.

Another thing I have noticed is that many electronic musicians have started using traditional instruments and songs, like Cepasa with Niby Chaiky or Serhii Russolo with Об’єднанні голоси (United Voices). Is there a danger of reinforcing national stereotypes?

Of course. I must say that I work mostly within the electroacoustic and classic music communities or the experimental music scene with Potopalskiy.

I know the music of Heinali and Kiritchenko, for example, which is something else. Kiritchenko can sometimes use elements of folk music because he worked with folk musicians in Kharkhiv, but now Kiritchenko has relocated to the UK. Kotra and Zavoloka can also use something radical, but I only really know these composers and not the musicians you are referring to. In the case of my colleagues they don’t often use folk elements.

Generally speaking, I am critical of utilising folk elements when this doesn’t lead to the production of something new, and is merely exploitative. It’s like in in the 50s or in Stalin’s time when orchestras used a lot of folk elements and clichés. This was more of an ideological rather than artistic choice.

Also, I have to say that I have a background in folk music myself and participated in many field recording trips. I don’t use this material often, it’s something really special. But we now have an open archive, so one no longer needs to travel to remote villages directly.

There are also some who use the texts from poets from the Executed Renaissance generation of poets.

There’s a film currently out in cinemas called Budynok Slovo – [Slovo House] which deals with the subject, and I did the music for this film. It’s very topical now because there’s a direct link between our generation and theirs.

How did you go about composing the music for this particular film?

The score is made of symphonic music for chamber orchestra and some jazz music performed by the Ukrainian jazz musician Dennis Adu. We went for something very simple and used jazz from the 30s, which is something I had already done on Povodyr, another film set in the same era, and the documentary Budynok ‘Slovo’. I have a score of music which was done for a musical revue for Les Kurbas, a film and theatre director who was also killed and worked in Kharkiv at the same time as the Executed Renaissance poets, so we know the kind of jazz music that was being played there at the time. It’s more or less a documentary. Denis Adu made an arrangement in the same style. There’s also some electroacoustic music in the film. The music is energetic, but slowly as the film becomes more sombre, reflective and more dramatic, I used horror music reminiscent of Hitchcock with violin, clarinet and bass clarinet.

Do you think young people in Ukraine are aware of their musical heritage?

If it’s someone from the music academy, yes, of course, but the real issue is that the whole value system needs to be put into question. For instance, when I was young they used to tell us that Mykola Lysenko was like a little Tchaikovsky or that Borys Lyatoshynsky was like a little Shostakovich. There wasn’t really a way to understand the role of Lysenko within the framework of our culture. Where is futurism in Ukrainian culture?

Now it’s a question of discovering the real value system of the Ukrainian musical heritage. Lysenko, for instance, is now a modernist composer for us, so nothing to do with Tchaikovsky. He didn’t belong, or didn’t look at the musical tradition of the XVIII century, his music is something else. Furthermore, he didn’t work much as a composer, but was more engaged in the Ukrainian educational system. Lyatoshynsky was also a modernist, but his music was hardly ever played because it’s difficult. It’s a lot more complex than Shostakovich and not comparable in any way.

There are many clichés and the thing is that many of the teachers at the music academies are still the same ones who taught my generation. The Philharmonic still has the same system and genres, luckily there is no Russian music, but the music from the 20s or the music of Roslavets, for instance, is not yet part of our culture, we still need to change the system. We still hang on to the same thinking of the 50s. We still have a lot of work to do. Like we need to put electroacoustic music on the curricula. Still, this year, I put on three concerts of electroacoustic music at the Philharmonic hall, so I am hoping that our generation can change things.

To go back to war and music, there have been elegiac and mournful pieces like “Bucha Lacrimosa” by Victoria Poleva, but, It might be my impression, or maybe I just don’t know it, but so far I have not heard anything like Penderecki’s “Threnody for the Victims of Hiroshima”, for instance, an aggressive and accusatory piece. Why do you think that is the case?

Poleva always composed music in this style. Also in the first days of the full-scale invasion she moved to Germany.

When I heard her piece it didn’t especially resonate with me, but this is entirely subjective. Poleva has always worked in this style. There is also a piece by Zoltan Almashi, “Mary’s City” (Music for Mariupol), who also writes post-romantic and post-modernist music, it’s his musical language. But, for example, the composers Roman Grygoriv and Illia Razumeiko wrote a “Lullaby for Mariupol” for Opera Aperta, which is a very active piece with bandura that conveys a more aggressive energy. It’s very pure, like something archaic and is something which is closer to my own way of thinking. Personally, I cannot think in post-modernist terms. For me it needs to be something very real. One needs to be more active than before the war.

I suppose then that the work of Valentin Silvestrov, and I am thinking as well of his Maidan Requiem, is not really your cup of tea?

I suppose then that the work of Valentin Silvestrov, and I am thinking as well of his Maidan Requiem, is not really your cup of tea?

No, it’s not my style. I adore Silvestrov’s Fifth Symphony where the music is complex and dynamic, but this “simple music” he has adopted since the 90s is very rational. One can say what type of reflection there is behind it. It’s like discovering something very simple and beautiful. I had many discussions with Silvestrov, he is very critical of my work and asks me why I make music that is so complex. “Alla, – he tells me, – look this apple, it is so simple and beautiful.” Yes, of course it is beautiful…

Do you think there will be a time when in Ukraine there will be a piece like Maessians’s Quatuor pour la fin des temps [Quartet for the end of time] or more time needs to pass with more distance?

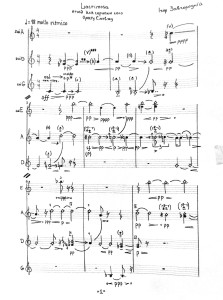

Maessians composed this piece during the war. He was relatively young [Maessians was 32 and a prisoner at the Stalag VIII-A war camp] but he wrote something tragic. Even Victoria Poleva, whom we were talking about, already has a well developed style of her own and her own musical language. For me it’s more interesting to hear something from younger composers. Oleh Bezborodko wrote something very good at the beginning of the full-scale invasion. But maybe the best piece for me is “Lacrimosa” for violin solo by Ihor Zavhorodnii. It’s not in the same musical language of Silvestrov and Palova. I actually have the music score with me, it’s very simple but complicated at the same time. He wrote a score for each chord which is not usual. Normally one would have a single line, but he wrote one for each chord. Generally speaking, the tempo would be 60, but he does it three times slower and all the while there are dynamic changes, so it keeps changing, but very slowly. It sounds like there are several musicians playing but in fact it’s just one violinist. For me it’s something more in tune with the times.

Has the role of music changed in Ukraine from one of pure entertainment to one of social engagement and is it necessary for music to carry a message of national identity under present circumstances or is music something else?

It depends from the type of musicians and musical communities we are talking about. There are many concerts now and many people come to listen to contemporary music, really experimental stuff. For me it’s a way of developing a community because it’s important to know that there are composers and music still operating in Ukraine and maybe there can be something new coming out like “Lacrimosa” performed by Orest Smovzh on violin. And music is something that can develop a community with a narrative, ethical and philosophical message.

It depends from the type of musicians and musical communities we are talking about. There are many concerts now and many people come to listen to contemporary music, really experimental stuff. For me it’s a way of developing a community because it’s important to know that there are composers and music still operating in Ukraine and maybe there can be something new coming out like “Lacrimosa” performed by Orest Smovzh on violin. And music is something that can develop a community with a narrative, ethical and philosophical message.

There are those who think that during the war one needs to make therapeutic music. At present there are many in Ukraine who use music as therapy and for me that’s not the case at all. I cannot imagine making music as therapy, or even “beautiful” music…

Do you think the international music community has responded in an adequate way to Ukrainian culture?

No. And I don’t know how this can be done. I had a lot of concerts but with little echo. Natalia Vorozhbyt’s play The green corridor, which is about four women who are refugees was rather successful. It’s a great show with humour and I would like to have this kind of response, but I don’t know if this can lead to direct political or social action. Cinema can maybe achieve this, and I am thinking of 20 days in Mariupol for instance.

The Canada Theatre made a show about daily life of a Canadian and Ukrainian couple who complain that there’s always Putin between them. It’s better to react with humour rather than in this sombre and tragic way, like Polova or Silvestrov.

I have been really impressed by the way Ukrainians responded with humour, and the always seem to have a meme at the ready.

Yes.

Is there anything you’d like to add of that your think it is worth mentioning?

Is there anything you’d like to add of that your think it is worth mentioning?

Well, three weeks ago I was at a conference in Paris at the Sorbonne about Ukrainian avant-guard music from the beginning of the XX Century to date. When I first heard of this I thought “how fantastic!” But when I got to the conference, I found out that there were only musicians from Kyiv there and I thought, why did I need to come to the Sorbonne to see my friends from Kyiv? I don’t need to go to Paris to see them. Even Silvestrov or Poleva are not part of contemporary music studies in Europe.

There was also a conference recently in Montreal titled “Music in difficult times” and I looked at the programme and there were no Ukrainians. There was a lecture about Gaubaidulina, [Post-Soviet Hauntology and the Music of Sofia Gubaidulina — Christopher Segall, University of Cincinnati] and one about Rwanda [La chanson au cœur du génocide rwandais — Christian Pariot, University of Toulouse] but the only mention of Ukraine was to compare the responses to war of Toscanini and Kerpatenko, the conductor from Mariupol who was killed for refusing to play concerts for the Russians. [Maestros Arturo Toscanini and Yuriy Kerpatenko: Professional Attitudes as Ethical Statement Against Oppression and Censorship. A Comparative Analysis in the Contemporary Musical Scenario — Chiara Antico, Universidade NOVA]. Amongst all the lectures there was only this one mention of Ukrainian music, and it’s tragic for us that to date there is still no international reflection on Ukrainian music.

So what needs to be done?

We need to write music and perform many concerts. We need to study English and be more active in communicating with the artistic and academic world. If you think of it, the Ukrainian Institute was only formed recently.

MAY 25, 2024 – KYIV

Your album autoportrack is one of the most inventive and personal to have come out of Ukraine since the full-scale invasion. Could you tell us about its genesis and how much of it had already been produced before February 24, 2022?

I made most of the tracks of the album before the full-scale invasion. The first track, “я нормально” [ya normalʹna – I am fine], with the music video where I dance in a strange way was created when the first news of Covid started to pop up. I thought, “Oh, the world is gonna be on fire soon.” I was sad and angry, and I wrote this song.

Initially I wanted to have a band, but the better musicians, the worse the band is, because every good musician has more work and less time for the band, as well as a big ego. We tried to make post-Soviet wave, but post soviet is not cool in this country anymore so it’s like future in the past music. And so I just started to make music by myself with a computer with Fruity Loops. I first used Fruity Loops maybe in 2015-2016. Then I began adding saxophone and it sounded interesting. I just used presets, I didn’t sound design much. The music sounded raw, and I liked it because it was straightforward and aggressive. At the time it suited me. Now I don’t really like this straightforward sound, but back then I was young, stupid, and hot blooded…

You say you started most of the tracks before the full-scale invasion, but at the same time the title of some of the tracks like “Genocide Idea” suggest the war was already on your mind. What was the production process?

I have a track on the album called “Sobornist” which I wrote just before the war. I felt something but I didn’t even post it on streaming services because I didn’t know how to do that. At the same time I did a post on Instagram two days before the war which was about giving hope and I posted this music. The track “Blat” is about corruption or something. “Mist Platona,” is an old track of mine, but I added the saxophone after the war, in a way I remixed my own track, so that now it has a new meaning. Some tracks are old and I like them without the saxophone.

Let’s go back a bit, could you tell us about your background in music?

Let’s go back a bit, could you tell us about your background in music?

When I was nine I went to music school but it was just something for children, nothing serious, but then, when I was 14 I decided to become a musician, so I went to a music college. I was playing really traditional jazz, but also played in a bunch of fusion rock bands and blues, and I was in a band that played funk, so different styles of music. We have a big jam community here called Fusion Jams and a lot of my musical identity was formed in that community. I also took part in different musical competitions, so I had a bit of a classical background too and when I was 15 I started to write bits in Fruity Loops. I did a little bit of this, a little bit of that.

When the war started I didn’t know what to do, but in the past a friend told me, “Maybe you want to play music for charity events and we can play for the army,” so I started to play during the war and my first solo performance was when the war started. During Covid I was actively writing and preparing for something, and when the war started I kept playing music.

A lot of people have told me that at the beginning of the full-scale invasion that they were unable to listen to music.

I stopped listening to music, but on the second day of the war I made a remix of an official hymn of the Ukrainian Forces just for fun, and maybe to calm myself. And then I didn’t do much for about a month when my father sent me to my babushka. There was a pretty calm atmosphere there, I had a computer, my saxophone, a piano and time. I started messing around because I had to do something. I thought, “War, war… but I can die as a better saxophonist, so I don’t care, I have a little bit of time to do something.”

You were saying that you’ve been doing a bit of this and that, but your albums autoportrack is very cohesive. How did you achieve this?

You were saying that you’ve been doing a bit of this and that, but your albums autoportrack is very cohesive. How did you achieve this?

Maybe I had an idea in my head, but it’s hard to articulate what it was about. I had a bunch of demos so I opened a new project and dragged all the demos I had into it and listened to every demo. And I was like, “Ok, this sounds like from one story, this doesn’t sound like it’s from the same story.” So I deleted everything that didn’t belong and left only what sounded from one universe. I had an idea that it’s just a story with little stories like we have a narrator, it’s saxophone, then we had some melodies, some bass, some drums, that mean something. Melody is usually the main character, the hero of this micro story. The bass has the role of faith because bass is the lower note, drums are like events that happened. In the track “Яд снаружі біль внутрі” [Yad snaruzhi bilʹ vnutri], which translates as “Poison on the outside, pain on the inside” I have a sound that actually describe this pain so it’s abstract concept.

Is the album a self-portrait?

Maybe for the person I was then, or maybe part of that person. You know, we are humans, we don’t have just one state, we have one small part that becomes bigger. Sometimes I have one voice, sometimes many voices. It’s not about me, but maybe about what happened to me. Maybe not just one portrait, but yes, it’s the story of a very lonely man. War changed me.

In what way?

Before the war I was a much more extreme guy. I didn’t talk to people much. Now I have a lot of friends. So it was like a healing process for me to produce this album and I felt much lighter in terms of weight and light.

You mentioned that your sound was somehow aggressive to begin with. How would you say it has evolved?

I didn’t write much music this year nor the previous one. I play saxophone a lot, I do a lot of live gigs and jamming, but I have not not been composing much. A week ago, though, I started to write again. Now I have become minimalist, and I have become lazy, I don’t want to make it difficult. I want to find a simple idea that sounds good without much editing. I want to catch a moment in a fast and effective way, not build something big and crazy like a gigantic robot that kills aliens. No, I just like to catch a small bird, just use a small drum loop, a small sample. The sound has to catch me in one moment, and I want to hear it forever. Maybe something like this.

How much improv is there?

In live performance? What do you mean?

In the recording process.

Usually I try to make it as effortless as possible, so I try to find a state where I totally understand what I am doing, and I am very sure of every note, and understand every chord and melody, so that I can improvise. I like messing around and finding interesting loops. When I use the saxophone, I like to layer saxophones on top of each other. I can mess around with form. I delete the stupid parts and the composition works automatically. When I don’t use the saxophone I operate like all hip hop producers with some samples and some loops that have grooves that push you further in the track.

Some of the tracks on the album are quite short, what is the rationale behind this?

This is because I had a lot of demos. I liked the sound of the demos, but didn’t have a project, I didn’t have patches or anything, I just had an MP3 or WAV, so I would delete maybe half of the song because it sounded too stupid but keep the first part if it was good.

What is the process like when you collaborate with other people?

I just listen to their songs, come to them with my saxophone, I improvise something or compose some part with them, then I go and they fuck around with that. I had one interesting collaboration with Yuvi. We worked on the composing process together, it wasn’t like I’d play the saxophone and then leave. I was like messing around with form and sound, so it was a real collaboration this time. I also have a track with a famous Ukrainian rapper, Otoy. I produced a beat for him and he rapped over it. I like to have one or two tracks with other artists so I don’t have that much responsibility. When I was in a band it was hard because it’s very time consuming and most of the time it’s not paid. When I became an artist myself with my own project, it became easier. I just play what the fuck I want, which I like to do. So I do small collaborations and I don’t know what I will do tomorrow. It’s easier this way.

The experimental music scene in Kyiv is very dynamic. How do you see it developing under present circumstances, especially after the new mobilisation law?

I don’t know. I am young, I just started my solo music career and the scene has been changing with me and I don’t understand how it is changing because the process was already underway. Some people have left. For me this is a natural process. I am 23 now, almost 24, so I have one more year to just chill [the age of mobilisation has been reduced from 27 to 25 years], but I have a lot of older friends who are afraid of mobilisation. We keep playing at festivals, but a lot of them use taxis to move across the city because I have already seen today in the metro that guys were checking documents not even on the platform, but on the trains. My country knows where I am. I have one more year and then I don’t know what will happen.

How do you feel about using war sounds in electronic tracks?

It’s ok, I don’t care, but when you use them in a very direct way it sounds stupid. To use the air raid siren is the most stupid thing for me. For someone who doesn’t have this experience, it’s ok, but when you are a Ukrainian musician and you use the air raid siren, or the raw shouting of soldiers or shooting tanks… Actually in that remix I did on the second day of the invasion I used the sound of German artillery but it wasn’t a serious musical piece, it was just me having fun.

Are there any Ukrainian albums that capture the war experience for you?

Are there any Ukrainian albums that capture the war experience for you?

Hmm… you know I am like a little musical snob, so here in Ukraine there isn’t much music I like. We have a lot of artists who are not actually musicians because in our country musicians don’t have enough money to become artists, and artists don’t have time to become good musicians, so it’s a little problem. In my case it’s hard for me to use words, but we have a lot of good poets.

We have some voices of our time like Palindrom he is good and he writes about today. The album warнякання, I will not listen to for now, but maybe in five years it will be more actual. It was good over the first months and maybe the first year after it came out, but then it’s like “everything is bad…” but in a couple of years it will sound fresh again like a capsule of time.

We have good producers, there’s a good female producer, Yuvi. She does not write about war, but you can hear war in her music. She is a virtuoso producer. Maybe you know Пиріг і Батіг? I don’t like their music much, but it’s fucking good words and poetry, as they use mostly poetry from the early XX Century. Also, Dakh Trio, a psychological and minimalistic act. Sophia, the singer, is so fucking good. She studied at the same college I went to. Maybe Stas Koroliov. Jockii Druce.

Were you born in Kyiv?

Yes.

And did the full-scale invasion make you question what it means to be Ukrainian?

Of course. Something so radically changed in one day, really in one day. And you didn’t even think it could be like that. We had war already with Russia before the invasion, but there was so much brain rot, and we always wanted to find compromise, but when I woke up with the explosions there was this realisation that compromise isn’t possible. I had a girlfriend from Lviv and she was always asking me, “Why are you speaking Russian, and why are you speaking Russian with your friends if you are Ukrainian? You speak Ukrainian with me and your family, but you speak Russian with your friends, why?” And I was saying, “It doesn’t matter, my friends speak like that…” Back in 2018 I had internet friends from Russia because I thought it’s the modern world, we can end it peacefully, but in 2019-20, I slowly started to realise and in 2021 I only spoke Russian with close friends who don’t speak Ukrainian and stopped chatting with any Russians and listening to Russian music.

Is there anything you have discovered about yourself since the full-scale invasion?

That I am much, much more of a coward than I thought.

In what way?

Before the war I was fearless, I wasn’t scared to die, I was just having fun. I had no problems. I had no money, that was my main problem, but I had no philosophical and ontological problems. When the war started I started to feel that I have a lot to lose. I was too childish, but now I became older faster than I actually am. I was younger than my body.

Is there anything you’d like to add?

No. I hope that you found something interesting in this word salad.

June 19, 2024 – USA

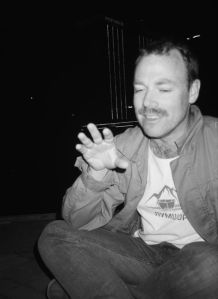

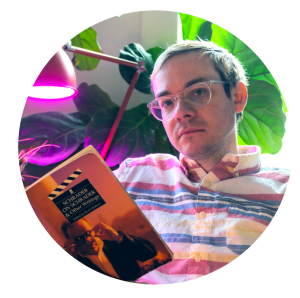

Photo by Melanie Barksdale

Could you give us an idea of your background in music and your musical journey? If I am not mistaken you come from a musical family but were always more into improvising than reading scores from an early age. How did you get from the viola to electronics?

Around 20 years ago I first purchased a pick-up for my viola, to amplify it for live performances. It was then I realized I could also plug it into my guitar pedals and make some wild sounds and do all kinds of things the acoustic viola could not. As my live performance approach evolved into more ambient, experimental, drone, and noise, so did my ear.

You have also studied with Michael Pisaro and you have collaborated with Alvin Lucier. What are the most important lessons you have learnt from them?

This question could warrant an entire book as a response! As far as my chamber music, and approach to sound as a spectral subject, these 2 mentors taught me a vast amount over the years. Form comes quickly to mind. Also, the idea of knowing every performance is unique (and embracing that). Both Michael and Alvin are very conceptual composers and the way they develop ideas into music shaped my approach to score making quite a lot, although they work within written notation quite differently from one another.

How did you get into music scoring and how would you say your “post-cageian” background equipped you for this line of work?

How did you get involved in 20 Days In Mariupol and what did you know of the situation in Ukraine prior to working on this particular project?I first got involved in 20 Days when I received an assembly from the Producer-Editor Michelle Mizner at Frontline. Michelle and I had worked together on a number of other films and she was referencing a lot of my music during the initial edit. I had been intently following the Russian invasion into Ukraine, which at that time had only begun a few months prior, but when I saw the early cuts of the film I realized this was going to be an incredible historical document. The care Mstyslav gave the people in the film mixed with the boldness to show what is never shown was, for me, unparalleled. So, when they asked me to score their film, I didn’t hesitate.

At what point did you get on board and how much time did you have to complete the score and how closely did you work with director Mstyslav Chernov?

I began working on the film in mid-2022, with the aim of finishing it for a December 2022 airdate. Michelle, Mstyslav, and I worked quite rigorously on it for many months. This was all over Zoom because Mstyslav was still working in the field. When it got into Sundance we pushed the airdate back and worked basically non-stop from December to January of 2023.

Without wanting to sound glib, how would you say your work on 20 Days In Mariupol differs from that of your previous scores for films like It Comes At Night in terms of creating and maintaining a narrative tension?

20 Days has an uninteresting form, it goes from day 1 to day 20, as one might expect. But within those 20 days we shaped 3 chapters: Surprise, Fear, and Escape. This is how we created a narrative musically. As assistant composer on It Comes At Night I can say Brian and I made some not so dissimilar music, but that was a very cinematic film with themes and variations and such, as you’d find in a typical horror film. For 20 Days the goal was to constantly feel dread, dismay, and a complete absence of resolve.

Again, without wanting to sound flippant, but did you draw from your work with Alvin Lucier and the post-cageian tradition while scoring tracks like “Flatlining”?

Good ear — yes, I did, very much. This is one of those examples of chamber music pieces that end up in film, as I mentioned earlier. Flatlining stems from a piece I wrote about 10 years ago called “Found Clouds.” I was exploring non-octave-reocurring scales at the time and recorded a version of it on a piano that was tuned for a performance of Ben Johnston’s “Suite for Microtonal Piano.” I would place eBows inside the piano and pluck the string. I did 3 takes and layered them, creating these still warm tones which interact with these sharper sounds. I thought it sounded lovely and self-published it on my label Editions Verde. Mstyslav thought it sounded like the absence of a heartbeat, the flatlining sound, so we used it a bunch in the film. I think it worked great, although now I hear this piece entirely differently.

The documentary is obviously very bleak but still maintains glimmers of hope amongst the tragedy, how did you manage to instil some light into the darkness in episodes like “The Baby Survived”?

This is one of the only instances in the film where there is music that has a tinge of resolve. Saving the harmonic resolutions for these moments was crucial in keeping the dread in the rest of the score. The timbre in “The Baby Survived,” with the synth and strings — and notably lack of noise, really helped bring this feeling of hope to this piece.

In a film like 20 Days in Mariupol, the sound design is very important. Did you also work with the re-recording mixer Jim Sullivan and Brian McOmber, the music consultant?

Almost all the sound design you hear in the film was done by myself and approached as score. Documentaries rarely work with sound designers, at least in the creative aspect, so it was up to me to build these noisey, unsettled, and brooding textures which you hear quite often. There is this rolling bass sound that comes back many times, almost like a giant snake coming up for air, that keeps the viewer on edge. We worked a long time to get these sounds just right and place them in the right moments.

Many Ukrainian musicians I have spoken to have told me they haven’t been able to watch the film yet as it is too close to the bone. Whereas, others, when I asked them how it was possible to convey the “war experience” to a foreign audience have told me that one could either spend 10 days in Ukraine or watch 20 Days In Mariupol. What insights would you say you gained from working on the film?

Many Ukrainian musicians I have spoken to have told me they haven’t been able to watch the film yet as it is too close to the bone. Whereas, others, when I asked them how it was possible to convey the “war experience” to a foreign audience have told me that one could either spend 10 days in Ukraine or watch 20 Days In Mariupol. What insights would you say you gained from working on the film?

Oh my god, that means the world for me to hear! I have heard from A LOT of Ukranians, especially during the awards season, who were just so so sooooo thankful the film was being noticed, talked about, and awarded. I am really grateful to get to work on films like this and it will forever be a part of who I am, what I experience, and how I walk through the world as long as I am able.

What do you hope an international audience might take away from watching 20 Days in Mariupol?

After the 20 days which the film portrayed the war did not end — it is ongoing. Obviously this fact is a horrible thing to remember, but we must. I think, to an international audience, the film portrays a universal experience of news-gathering in the current era, through the eyes of an Associated Press journalist. The AP is everywhere and is known in just about every corner of the world, so I think through their eyes it helps people connect with the film. Mstyslav takes it from there, though, and that is the most interesting part I think for audiences: what comes before and after the 10 second clip you see on TV. I know we are all curious to know the truth, and this film gives you access to angles of journalism that is very rarely shown to the public.

Have you visited Ukraine and if so, what were your impressions?

The closest I’ve been to Ukraine was spending a few weeks in Ostrava in the Czech Republic, a town on the border with Poland. There are many, many places in Ukraine I’d like to visit and hope to do so when I am able.

Are there any Ukrainian artists and / albums you find inspirational?

There are many. Of note lately are the artists Mykhailo Chedryk, Fima Chupakhin, and Ksenia Stetsenko.

JUNE 19, 2024 – ON TOUR

The Lazy Jesus

The Lazy Jesus

I’m a sound producer, musician, and DJ from Kyiv, Ukraine. Before starting my solo career, I actively performed as a session musician in various bands. I also worked in the A&R department at the label Masterskaya, owned by Ukrainian artist Ivan Dorn. Additionally, I was a resident of the HVLV club and the breakbeat formation GRV GRV.

Has the full-scale invasion changed the way you think about music and sound in general, and has it had an impact on your setup and playlist?

The only impact this event had on me was that it pushed me to realize my long-held idea of creating a program using the folk heritage of my country more quickly. For a long time, I wasn’t sure about the style and sound I wanted to achieve. Considering my recent passion for percussion music, I developed a vision to create a product that combines melodic Ukrainian roots with percussion from around the world.

Your latest album UA Tribal Vol 2 delves into the roots of Ukrainian music. How does one reinterpret and integrate traditional instruments and sounds in a modern way without running the risk of reinforcing cultural stereotypes?

Ukrainian folk elements in a modern reinterpretation have also proven to be popular with an international audience with acts like Dakha Brakha introducing sound marks from different parts of Ukraine. At the same time Ruslana famously won the Eurovision Song Contest back in 2004 by repackaging Hutsul culture in a pop format. Your own “anthropological journey” seems to tap into a wider context with collaborations with Peruvian and Argentinian producers. How did this “fusion” come about?

Ukrainian folk elements in a modern reinterpretation have also proven to be popular with an international audience with acts like Dakha Brakha introducing sound marks from different parts of Ukraine. At the same time Ruslana famously won the Eurovision Song Contest back in 2004 by repackaging Hutsul culture in a pop format. Your own “anthropological journey” seems to tap into a wider context with collaborations with Peruvian and Argentinian producers. How did this “fusion” come about?

At a certain point, I realized that to fulfill my mission of presenting contemporary Ukrainian ethnic music on the international stage, it was time to take the next step: collaborating with artists who inspire me and have significantly influenced the direction of my work. I was very impressed by JaiJiu’s music when I first heard it and immediately suggested he create a remix for my upcoming album. I met Dengue Dengue Dengue at one of their performances, where we found common ground in the idea of live performances in masks.

What can you tell us about the production process for UA Tribal vol 2 and how long has the album been in the making?

What can you tell us about the production process for UA Tribal vol 2 and how long has the album been in the making?

Overall, this material was created quite rapidly. I wrote the first part of the album, released at the end of 2023 at french label Shouka, within a month to present it at the anniversary of our collective, GRV GRV, in Kyiv. Throughout 2023, I produced enough material for four albums, each distinct in style and sound. These will include more commercially accessible tracks as well as more electronic club-oriented compositions.Many of the Ukrainian artists I have spoken to are critical of sharovarshchyna and bayraktar-core. What is your feeling of their actual impact within Ukraine society?At any given time, there is a low-quality pop segment that exploits current trends. It’s in our mentality to criticize our own for any actions. To please the Ukrainian people, one must be very skillful or have good karma. 🙂

On a general note, would you say that the role of music in Ukraine has shifted from one of entertainment to encompass the expression of identity, communication, and emotional and physical survival?

To be precise, music’s role has not shifted entirely into this form; rather, this segment has been added. When you look at new music playlists now, you can still find plenty of entertaining tracks. The trend towards identity was quite strong at the beginning of the war, but now people have learned to live in wartime conditions, and life cannot go on without the entertainment segment.

After two and a half years since the full-scale invasion, how can one keep “All eyes on Ukraine” at a time when the international attention is diverted to Gaza and Israel?

After two and a half years since the full-scale invasion, how can one keep “All eyes on Ukraine” at a time when the international attention is diverted to Gaza and Israel?

The decline in attention is a natural process. The war in Ukraine is no longer new to the international community and news outlets. People are not particularly concerned about events happening far away until tragedy and hardship reach their own homes. Naturally, artists who have the opportunity to tour try to convey the message that the war is still ongoing, but unfortunately, these efforts are just drops in the ocean.

Which book / film / album / song / traditional dish / podcast / blog / artwork / building / meme best captures Ukraine for you?

The album O vesna, vesna by Mlada is one of the best Ukrainian albums for me.

NEW RELEASES

s/t ~ Ross Khmil, Anthony Junkoid and Andrii Strakhov

One day, among the secluded depths of the Inner Kiev region, a spiral center of music was discovered – three people gathered around it, one conjured, the second called, and the third conjured – time passed and the fire of sound took on an extensive form full of implacable passion, cacophonous mysticism and emitting an invisible but important message

All music by Ross Khmil Anthony Junkoid Andrii Strakhov

Mastered by Ross Khmil

Cover art by Andrii Strakhov

Soundots ~ Dark Circuit

We created Soundots in early 2023 as we wanted to implement our vision of the iconic 90-2000’s trip-hop sound. About a year and a half was spent working on the “Dark Circuit” album which symbolises a tedious path filled with personal and group crises.

Recording and mixing was done in a home studio owned by Yuri, who has worked on the Monotonne project and is part of the Dnipropop label.

The album features a dark, textured lo-fi sound with rich harmonics, shoegaze guitars, modulated keys, vocals recorded into a mobile dictaphone, which altogether makes our album expressive and reflects current times. Thematically, the album is about reflecting on wartime: loneliness, uncertainty, mental escape — and realisation that tomorrow may not come for everybody, like in the Ukrainian Insurgent Army time folk song “Not All of Us Will Be There” song (featuring Valia Levchenko).

Which, by the way, is this album’s yet another feature: the tracks feature musicians from Ukraine, the UK, and Canada.

Cover photo by Taras Yakobchuk.

58918012 ~ Three States

“Hello! Honestly, I am not even sure if anyone noticed that one of my early releases (Three States EP) has been taken down from all the platforms. And it was not by accident. Let me explain…

At the beginning of my ambient music journey (in 2020), I had an idea to make a release where I would describe three states of matter in music. And I did it. BUT! I used russian language (read — the aggressor, terrorist, killer, and the enemy language) in that release. Let me explain once again… Of course, after the fall of ussr my little childhood world was saturated with russian “culture”, and in my head, for some reason, etched the voice of a narrator on a science telecast of these years. So, I’ve tried to bring that childhood taste into that release, using my own voice of course.

As you all may know, in February of 2022 russia started full scale war against Ukraine (just in case, if somebody didn’t know). I’ll be honest, I totally forgot about that EP at this point because I am releasing a lot of music all the time. But recently I remembered it and I immediately removed that EP from everywhere. But from the musical and conceptual perspective, it was very close to my heart, and I think that somebody liked this music as well. So, I decided to re-imagine it.