Ukrainian Bull by Mariia Prymachenko

Lots of in depth interviews this month mostly recorded back in May in Ukraine which you can both listen to and read. In Dnipro, I reconnect with old friends Roman Slavka, Eugene Gordeev and Igor Yalivec to talk about Module and the local scene.

In Kyiv, I discuss the whole notion of the “good Russian” with Giorgiy Potopalskiy, one of the very first artists to feature in Ukrainian Field Notes back in March 2022.

Furthermore, Oleksii Podat shows us photos from relatively safe spaces and puts things into perspective through his experience with war in Sloviansk back in 2014.

A welcome tea break came courtesy of Oleksandr Ostrovskyi and Tetiana Novytska from the classical music website The Claquers (which has just published and in-depth interview with ACL favourite Katarina Gryvul) while Gordiy Starukh plays the hurdy-gurdy in Krakow.

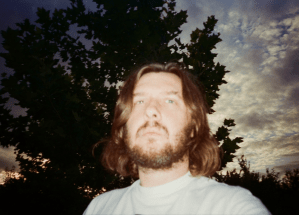

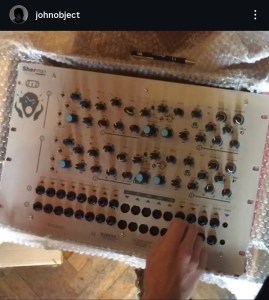

John Object photo by Sasha Maslov

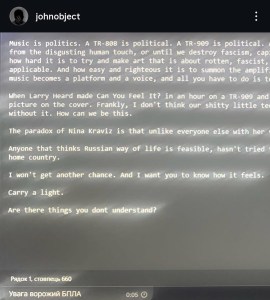

But to begin with here is the monthly UFN Resonance FM podcast with John Object one of the most outspoken and interviewed electronic artist in Ukraine.

Tracklist

John Object – 500mg [VA – Intermission]

John Object – Demo New Life Immediately (2015) [Life]

John Object – Famous Eyes (live 2021)

Група Б – Нічні кімнати [Drones for Drones, Volume 3]

John Object – East Piano [Piano]

birdsandpeople – Bakhmut Song [Syndrome]

John Object – Kiss (Live 2020) [Sweat]

The full trascript of the interview is at the end to respect the chronological order the interviews were taken. Ad yes, it is our longest interview to date.

This month we also have three more podcasts which are to be found below before their respective interviews. But before we do get stuck in with the interviews, here’s the usual Spotify playlist featuring our interviewees and recent releases.

@jonas.gruska

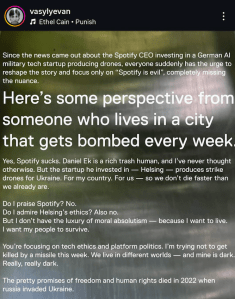

On the subject of Spotify, a few international artists recently pulled their material from the streaming site in protest to David Ek’s investment of more than €600 million (around $640 million) in Helsing — a German defence technology company that produces and supplies AI-powered drones, including thousands already delivered to Ukraine.

Criticism of Spotify has long been rife in the blogosphere. “Being on a streaming platform that pays musicians so unfairly has always been annoying, but somehow I could live with it,” is a typical example (@thebluesagainstyouth) generally followed by a variation on the following, “Daniel Ek’s investments in AI weapons cross a line for me” (@sleeppartypeople).

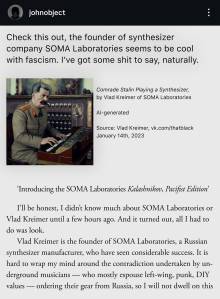

The tipping point for many has indeed been the headline news that Prima Materia, the investment company founded by Ek and early Spotify investor Shakil Khan in 2020, has doubled down on its original investment in Helsing with Ek becoming chairman of the company. This was enough to unleash a frenzy of outrage from “leftsplaning” bands raging against the war machine. Not everyone was impressed. And not just in Ukraine.

The tipping point for many has indeed been the headline news that Prima Materia, the investment company founded by Ek and early Spotify investor Shakil Khan in 2020, has doubled down on its original investment in Helsing with Ek becoming chairman of the company. This was enough to unleash a frenzy of outrage from “leftsplaning” bands raging against the war machine. Not everyone was impressed. And not just in Ukraine.

We have never been great fans of Spotify here at ACL either, but for Ukrainians who are trying to survive and have seen the delivery of Patriot Systems being halted, only to be resumed a few days later in the now customary Trump’s decision making roller coaster, this moral outrage is possibly misplaced.

Tellingly, the debate revolves mostly on what the best streaming services might be, rather than engaging on the actual topic of drones. Instead of scrutiny into Helsing’s ethical claims, calibrated on the Economist’s democracy index, critics prefer to conflate Ek with AI warfare, facial recognition, ICE and the Trump administration, turning this into a US centric argument. The fact that the Spotify crusade is led by bands that seem to justify, or at least explain, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine as a response to Nato expansionism highlights how ideological the issue has become.

Yes, Ek and Prima Materia have made an investment and are looking to make a profit, that’s what investors do. Helsing have always sought to attract a broad range of investors, while committing to remain independent with plans to take the company public in the future rather than sell.

And no, this is not an ad for Helsing, who have made a long-term commitment to Ukraine, but whose own track record is seemigly contested. But their AI sofware is currently saving lives in Ukraine. And yes, there are other similar European startups such as Tekever and Quantum Systems also doing very well. At the same time, there are also Russian made drones, the MS001 for instance, that use Nvidia tech from the US. To focus on Ek is a distraction. Whether one likes it or not there is a war in Europe, one that the EU has been unable to respond to effectively.

And no, this is not an ad for Helsing, who have made a long-term commitment to Ukraine, but whose own track record is seemigly contested. But their AI sofware is currently saving lives in Ukraine. And yes, there are other similar European startups such as Tekever and Quantum Systems also doing very well. At the same time, there are also Russian made drones, the MS001 for instance, that use Nvidia tech from the US. To focus on Ek is a distraction. Whether one likes it or not there is a war in Europe, one that the EU has been unable to respond to effectively.

ACL might not be the right forum to discuss such issues in depth, but this is also the reason I started this series in the first place, as the voice of Ukrainians on the receiving end of unrelenting shelling is all too often missing from the discourse. A number of the artists I have interviewed over the course of three and half years have had to learn to make and operate real drones, as this 30 minute documentary on Arte featuring Ice and Petstep, both from Dnipro’s electronic scene, testifies.

So, to better understand the reality of the battlefield in Ukraine, let’s hear it from Nataliya Gumenyuk, a Ukrainian journalist embedded on the frontline. But before that, a quick disclaimer, all of the above does not reflect ACL’s editorial stance, it is my own personal position.

To close proceedings we have a great batch of new releases courtesy of Igor Yakimenko, LUCIVORA, SHKLV, djsnork, ROSS KHMIL, xtclvr, Natalia Tsupryk, Rudni, invisible noise monasticism/нойз галичина, Manoua, and two VA compilations from Telesma and Shum Rave, the latter one made from their recent sample pack from Crimean Tatar musicians.

In the viewing room we feature Katarina Gryvul, Cepasa, Tucha and Sawras.

As a closing remark, it is sad to note that the Russian cultural offensive is back in full swing with Anna Netrebko and Valery Gergiev set to appear on the international stage in a busy summer schedule. Both Netrebko and Gergiev are supporters of Putin. Gergiev, in particular, will be conducting Tchaikovsky’s 5th Symphony at the Reggia di Caserta in Italy under the usual (naive or complicit) pretence that art should be divorced from politics, blindley ignoring how Russian music has been weaponised.

I hope you’ll find something of interest in these pages. UFN will be back in September.

MAY 22, 2025 – DNIPRO

Roman Slavka – Egene Gordeev – Igor Yalivec

From L to R, Parking Spot, Roman Slavka, Eugene Gordeev and Igor Yalivec

Roman Slavka: I am a musician from Dnipro and now with my friends Eugen and Igor we are in Spalah a place where we can do a lot of different events especially for experimental music, dance music. The majority of events are deejaying with drum and bass, and electro. However, this is also a place where we can raise funds for our friends in the army.

The biggest change since the full-scale invasion is that more and more people from the music community in Dnipro have been joining the army and we are doing our best to collect donations for them because they really need our help to purchase cars, drones and medical equipment. The main goal of this place is to raise funds. For instance, we have a free donation option for those attending parties, like 100 or 200 hryvnas [2-4 Euros] to help our friends on the frontline.

In terms of the music scene, as I mentioned already, since a lot of guys are on the frontline and not many can do music right now it has become more complicated to present Dnipropop as a label compared to 2022.

In terms of music, we do mostly experimental stuff or ambient. Personally, I am switching from ambient to more dance-oriented music, I don’t know why, it can be just something simple like a kick, or snare.

Dnipro has not been occupied as yet, but we have issues with air raids, with some explosions around, etc and dancing can be a way to deal with our stress. Sometimes you just need to produce some techno music!

Eugene Gordeev

Eugene Gordev: I am the composer, lyricist and vocalist from Kurs Valüt. Roman Slavka has already said everything that there was to say.

I met your other half in terms of Kurs Valüt, Eugene Kasian, last year in Kyiv, is he still based there?

EG: One man is based in Dnipro and the other in Kyiv.

So, how do you work together?

EG: Through audio messages.

RS: It’s a process, not only for Kurs Valüt. Other bands are also split in different locations and communicate by sending audio files. Then Eugene goes to Kyiv to work in the studio. With other bands, the bassist might be in Lviv, and another band member might be in Dnipro, so they exchange audio files and record separately, but it can still work.

EG: Next question please?

Didn’t you sign to a German label?

EG: Now we are in the process of transferring all rights that were held by the label back to Kurs Valüt as our contract is expiring soon. But I am very grateful to the label for all they have done, it’s been a very good collaboration.

So when is the new material coming out?

[General laughter]

Igor Yalivec

Igor Yalivec: We ask this question every time we see Eugene!

EG: Soon. In Summer.

IY: Ok, my name is Igor Yalivec. I am a composer and sound designer from Dnipro. Also, I have a band called Gamardah Fungus, we make ambient music, experimental, electroacoustic, with a bit of doom, metal, even. However, we are now taking a pause because Serhii, the second half of the band, says it is too hard for him to play and compose and make live shows. Still, even if we are taking a pause, during the past three years we recorded an album that we hope to release in Autumn. It has been longer and harder to make than any of the previous albums and it will be very different. We won’t play live until the end of the war, so for the time being, Gamardah Fungus will remain a studio project, I think.

Personally, I also have a solo project under my own name. I released two albums before the war and one that came out after the full-scale invasion in 2023. But now I also don’t compose anything new. It is interesting because while Gamardah Fungus has taken a pause in terms of live show, as a solo project I keep performing even if I am not producing anything new, whereas with Serhii we are still composing. So, it’s the opposite.

The war changed our production process but, as Roman said, we try to do our best and collect donations for the army. Dnipro is very near to the front.

Would you say there is a specific Dnipro sound?

Roman Slavka

RS: We have a label called Dnipropop, so it should represent the Dnipro sound.

EG: No one else represents the Dnipro sound. We are the Dnipro sound!

RS: But in terms of music, if you go to Dnipropop label and listen to our releases, it’s very different music in different genres, it might be ambient, IDM, or Kurs Valüt.

EG: There is a little bit of experimental music, and a little bit of crazy stuff, but not a lot. All this is mixed into one sound.

IY: Before I forget, the Dnipropop label is very interesting right now because it is like a mixture of many genres but if you look at the history of music in Dnipro, – we lived here all our lives, Roman and I are from Dnipro, Eugene is from another city but now lives here, – and there were a lot of genres that were representative of our city in different years. Dnipro was the capital of Drum and Bass maybe 20 years ago; then there were a lot of experimental small bands and groups, rap and hip hop bands. And there were many deejays in Dnipro that were representative of house in Ukraine. And now it is very interesting that during all this time our sound is a mixture of all these genres.

RS: Something between Drum and Bass and house music with some rap.

IY: I think it is because we all tried many different genres. We experimented a lot and now we found something very authentic for Dnipro and we are very proud of this.

I want to get a sense of how big the community is, how many of you are there and is this one big happy family or is it a dysfunctional family like most families are?

RS: I think this is a huge family… hmm, not huge but yeah, our relationship is great. We are friends and we can help each other, not just in music, we do not compete with each other, we prefer to do things together at events We understand that we can help each other, not only musically. If our friends on the frontline need something we usually do this. We never compete with each other, we prefer to do everything together, like events. Also, a lot of musicians from Dnipro went to the Module Club and did like a live electronic jam, like jazz but with electronics, and the goal was to listen to each other, not to compete. Sometimes it was a hard task but usually it was a great type of communication.

And the second thing that is really important right now, is that fortunately we have this new blood because for ten years we had this gap where almost no one joined the electronic music scene here in Dnipro. It was a strange case because we did a lot in our 20s, then we took a break to build our careers and when Module opened, we could play again like we did in our 20s but the majority of people from that community was 35-40 years old. Fortunately, now we have new names, and we try to help, like Eugene and Yura [Yuriy Bulichev aka Monotonne] help them in their production process and I already see the results in the work of Parking Spot or Toucan Pelican, who released an album on Dnipropop a few months ago. It’s really great and interesting stuff; it’s really professional stuff thanks also to Eugene and Yura.

Can we actually talk about Module now?

IY: Eugene can talk about Module, because he was there from the beginning.

RS: Eugene wrote an essay for the second issue of POMIZH magazine, an art magazine created by DCCC [Dnipro Center for Contemporary Culture], about the history of Module because it is a very complicated history and it will be published both in Ukrainian and English. You will be able to read it there, but Eugene can tell you something about it now. He arrived at Module like a man from the street with a proposal for the owners to make minimal wave parties. So Kurs Valüt was created to popularise this style and invite other groups. It was some sort of bluff, as Eugene didn’t have anything. He created this whole new project in eight days because he had like this free time slot between different techno parties. And this is how it started.

So the club itself already existed?

Yes, but those were the first weeks of its opening.

And what kind of club was it going to be?

IY: Just to clarify, there were two men behind Module, Mykyta [Kozachynskyi] and Eugene, another Eugene, [Honcharov]. They are now in the army. They founded this club, it was like an art club, it was meant to be a club for music and art for the community. At the same time, Eugene [Gordeev] also came to the club, and we all got to know each other. It was never meant to be a club for just one genre, techno or house or even just music. Also, there were some exhibitions with artists from Dnipro and various performances, not just music but also theatre. But, yes, most of the events were musical even though that wasn’t the original aim, maybe it was because we were mostly into music. And when DCCC started, the community expanded with artists and musicians. Since Module closed down [before the full-scale invasion] our community now holds events here [at Spalah] and DCCC.

Sorry, what year was it that Module opened?

RS: It’s a good question.

EG: 2016.

RS: Yeah, a third Eugene [Kasian], the second Eugene from Kurs Valüt, he was the art director of the Module Club before stopping to concentrate on his work with Kurs Valüt, but all these guys were involved in the club for its first years of existence, and contributed to its development and to its culture.

EG: It was the best club in the centre of Ukraine in my opinion.

RS: It is not a joke; it was the biggest and best club in terms of music in Central Ukraine, because usually all clubs with techno and experimental music are based in Kyiv and Module was the place were we could invite artists from Kyiv and make events.

What was its capacity?

EG: Four hundred people.

IY: But it had a yard, the club was located in a private yard and there were held in the yard itself, so 400, plus another 400. For the most popular events we had 800 people, something like this.

And did it have a regular programme?

RS: Yeah. Every weekend they had parties. In terms of spaces, there was a main stage, the yard and the Module Lab — a chill-out area and a venue for lectures. We also used this space to play experimental music during techno events on the main stage. Additionally, we recorded videos of our lives during the COVID-19 period in this location.

EG: Two studios.

RS: Yeah, two studios where Yura [Yuriy Bulychev] and Maxandruh worked. Also, this lab was a space made especially for experiments.

EG: Vegan.

RS: Yes, that’s where the kitchen was.

IY: It was a really great place for the community with any taste of music, art… I think Module is the place that really connected people at the time.

EG: A people’s blender.

So, in terms of the music…

RS: Eugene says it was more about the sound, rather than the style. The sound was supposed to be raw, and yeah, the majority of parties were techno, but sometimes it was house techno, etc, but this was the main idea of the place…

EG: Andrii Deme made techno.

RS: Yeah… and maybe the main idea of the place and maybe the Dnipro sound in general.

So, when the full-scale invasion happened, at what point did Kozachynskyi and Honcharov enlist and closed the club?

RS: The club had already closed before the war, because the owners…

EG: It was Covid.

RS: The club worked during Covid the way clubs did then, but the final stages of the club were a few months before the full-scale invasion, as far as I remember, and the reason was not because Mykyta joined the armed forces, there was an issue with the owner of the place who also owned a huge building by the club and he didn’t want young strange people near his expensive flat and that’s why he did a lot to close the space. As far as I remember, local government and the mayor tried to find another space, but everything they suggested was really awful, somewhere not in the centre or derelict. Before the war, Eugene Honcharov found a place and started thinking to reopen Module but unfortunately the full-scale invasion happened so Spalah and DCCC will need to function as some sort of new Module for the time being because here we have almost the same people with the same ideas of how sound and art should look like.

Ok, can we talk a little bit about Spalah, when did it open and how does it work?

RS: Yeah, this is the second Spalah. The first one was a really interesting place, but was half the size of this place. I found it on Instagram because I saw a place where a lot of people were drinking and dancing but when you got there it was a shock because it was a really small space, the kind of place that looks crowded even with 10 people. But then Mykyta decided to rent this space and here we have more space allowing them to make far more activities, not only techno, and drum and bass events but some sort of art lectures and so on.

EG: Spalah is the next people’s blender.

Sorry, I am a bit confused. You were talking about Mykyta but is it the same Mykyta as in the Module club?

RS: You know, in Ukraine we have a lot of Eugenes and a lot of Mykytas… but we have only one Igor and only one Roman!

Yes, it’s different people. Mykyta Kozachynskyi is the co-founder of Module and he joined the army at the beginning of 2022. Mykyta Shpak, is the owner of Spalah and he joined the army about four months ago.

Are there any other venues aside from Spalah and DCCC?

RS: In terms of the music we make it’s just Spalah and DCCC. There are probably other venues for popular dance music, but it’s not about electronic sound how it should be.

Do you have connections with other venues or cities like Kyiv, Odesa or Lviv?

RS (translating for EG): Yeah, these connections exist and started during Covid. Eugene and other guys from Dnipropop created an online event called Intercity. The idea was to link ten different communities and venues to represent the electronic music in different places. These communities still exist like Shum Rave from Sloviansk. They used to take part in events at DCCC. For example, now they are going to release an album inspired by Crimean Tatar music based on a sample pack with sounds from Tatar instruments. This is a way for us to collaborate not only in terms of support and communication, but also by doing music together with artists from different regions.

Also, artists from Odesa, Kyiv, Kharkiv usually play here. It is a typical Ukrainian thing that we collaborate when something goes wrong. Like when Covid started we rallied around the club industry, same with the full-scale invasion, we work together with a common goal.

For example, the club Abo in Kyiv is very similar to Module, even Mykyta, the founder of Spalah has said so.

You mean the record shop Abo?

RS: Yeah. They are from Kyiv, but they do a lot for the Dnipro community and the Module squad who are now in the army, and this is an example of how different communities from different cities can help each other.

Can we talk about new blood? You were mentioning Parking Spot and Toucan Pelican earlier. How do you connect with younger artists?

RS: That’s a question for Eugene because Parking Spot released on Dnipropop. Parking Spot performed at DCCC, which is the kind of place you can go and say, “Hey, guys I am doing this stuff, and I want to perform here,” and Yuri Bulichev and Eugene saw him and asked him to join the Dnipropop label and released his album. He also took part in VA albums.

I think that with Toucan Pelican it was a similar story. Eugene talked to him and really motivated him to finish his album.

IY: I think in Dnipro there is the most powerful artistic community now in Ukraine. Only Kyiv can challenge us, but Dnipro is the first one. I think it is not just my opinion; it is really so. The most interesting events, musicians and art projects are from Dnipro and Kyiv. And a little bit in Lviv.

RS: Because Ship Her Son has moved to Lviv. He was born in Dnipro but now lives in Lviv.

EG: Also, the owner of Closer, the best-known techno club from Kyiv is from Dnipro.

IY: So, Dnipro is the capital…

RS: Of everything!

EG: Stanislav Tolkachev is also from Dnipro.

IY: Ah, there is also a famous techno producer, Stanislav Tolkachev who is also from Dnipro. And there is another very famous deejay, Topolski, who is from Dnipro. He was in the armed forces and is now in Kyiv. They make shows to support the army. So, every nice producer needs to be from Dnipro or to live here for some time. It’s a joke but…

RS: But no!

How do you see the future?

RS: We are waiting for it to be over, but once it will be over we expect it to be really interesting because the guys from the army they will see things in a different way and I hope, and expect, that the majority of them will try to find new ways of working with that experience in different artistic practices, in music, in sound design in photography. I hope this is how things will turn out to be, but again no one knows when the war will end. This is the biggest issue in Ukraine right now because it doesn’t look like it is going to be easy nor in the nearest future, and as I mentioned before, more and more guys from our community are joining the military. There was a first big wave, then a second one and probably some of us will be in the third one because we still need to protect our country.

[The interview was edited for length and clarity]

MAY 28, 2025 – KYIV

Georgiy Potopalskiy

I don’t know if it’s a good way to start this, but I am from russia, I am from Moscow, but I have been here in Ukraine for more than 15 years now and I consider myself to be Ukrainian. I don’t have any contacts with russia anymore and I don’t want to have contacts. So, it’s like I turned the page.

I don’t know if it’s a good way to start this, but I am from russia, I am from Moscow, but I have been here in Ukraine for more than 15 years now and I consider myself to be Ukrainian. I don’t have any contacts with russia anymore and I don’t want to have contacts. So, it’s like I turned the page.

As a musician I started my project in some bands in Moscow. As it is common when you are young, I had a band with my friends from school, and we played some experimental punk-core music. However, when I came to Ukraine, I found myself on my own and I decided to go deep into electronic music. So, in 2007-2008 I started my project Ujif_notfound. I called it this way because after I escaped from russia, nobody knew where I was, hence “notfound.” Now you know.

The chief idea was for me to learn some program where I could do some media art. Back in the 00s this stuff was very popular with people like Ryoji Ikeda and Alva Noto and many more. That was like the chief thing I wanted to do, code, minimalistic audiovisual stuff with sound and vision. That’s how I found the program Max MSP, which was really interesting to me. At the time there were no manuals, so it was very hard for me to learn this program. It was like an empty window. I didn’t understand anything, and it was a big challenge for me. Here in Ukraine, I was one of the first to use it. I had only one friend who is also an audiovisual musician, but I only found him three years after I moved here, so I spent like one or two years at home making my patches on my own.

My first albums were really minimalistic, and my first shows were with Dmytro Kotra, Katya Zavoloka and Andriy Kiritchenko at Detali Zvuku and later the Kvintu Festival. These were the first festivals, and my first albums were also released on Dyma’s label Kvintu. And I still work with Dyma to this day.

At the Detali festival I also saw an artist who was very strange for me because she played experimental music. The festival had young people making noise, but this woman played the most impossible music I ever heard. That was Alla Zahaikevych, a teacher from the conservatory. For me it was incomprehensible how this woman could be at this festival. I decided to speak to her, and I told her, “It’s amazing music, I would like to know how you made this.” She told me she was a teacher and had made this music in Super Collider, a very difficult program with scoring and so on. I asked her if she could show me how to make music with this program, and she said, “Ok, come to the conservatory and we will see.” I went to see her, and she asked what I was doing. I showed her my patches on Max MSP, and she said, “Wow, this is very interesting. Max MSP is used in all music academies, so it would be nice if you could teach this in our conservatory.”

I started facultative classes for students and for two years I run the Max MSP class in the conservatory. That was strange because at the time, the students didn’t have computers, they were classical musicians with violins and stuff, and they came with pencil and paper and drew my patches from Max MSP but never tried them in practice as they didn’t have the opportunity to do so.

Sorry, remind me what year was this?

2008-2009 maybe. But then the following year, the students already had laptops, and it was really cool and I was surprised because in the space of a few months some of the students became really professional with Max MSP and they started being cool electronic musicians.

Then I went through a long period of doing gigs, and played at Kontrapunkt and Plivka, so I was playing in clubs with many guests from all over the world with experimental music and DIY indie, something like this.

In parallel I had my own projects with media art and exhibitions in museums.

So, is there always a visual element in your work?

Sometimes they’re installations, and it’s not always visuals but interactive. You can see on my website. It’s probably 50% maybe. And also, you know, my work with Alla is something different, it is electroacoustic music. And my work with the label Kvitnu, and now I Shall Sing Until My Land Is Free, is more about experimental electronic music, not media art.

Ok, can you tell me how your music has changed since the full-scale invasion?

For me it’s a really difficult question because when the full-scale invasion started, I decided that music was like a closed chapter until my land was free! I decided that what I wanted to do was to help the army. I started working with my friends, we have a company, and we make FPV [Firs Person View] drones. Now we are already a big company with many products that works on the frontline, and we have a production line and so on. This is my main job at present, but I understood that after working five days a week, and even seven days a week before then, I now feel like an engineer in an office, and this is really hard for a musician or any artistic person…

Sorry, this company… is it like an independent company or is it associated with the military and how is it founded?

Sorry, this company… is it like an independent company or is it associated with the military and how is it founded?

It is hard to say because you know how it works in Ukraine, we have our war, it is DIY war and it’s half from the government and half absolutely pirate. So we have like a NATO certificate for of our products, but on the other hand we can go to the frontline without any documents, and we can test the new stuff that we make by ourselves without any permission so it’s like pirate. But we also have Prytula, I don’t know if you know this guy, this crowdfunding company, it is the biggest one in Ukraine and this guy helps us so it’s now under the government like this.

How did you learn to make drones?

When there is a war in your country, you can make amazing things you didn’t even believe you could make. It is not so difficult. We knew one guy, a friend of ours, who is a really cool engineer. He never worked with drones, but he’s like a genius programmer. He has his own company, some project with google, something like this, and he’s from Kharkiv and when the war started, he closed his company and invested all his money in developing drones. He is a really genius guy and he made amazing things that are still the best in Ukraine at present. Once he came to me and asked me if I wanted to make a plane and I said, ok. So he just told me, “You need to take this and this and now it’s your turn to develop it and think how this can fly.” So I did it and it works very well actually. This little plane works like a… I forgot the English word, like a predator. So this plane is preying on other little aircraft from russia.

Tell us about the music and the album Hypogonadism which is the first one you made after the full-scale invasion.

After I decided to be an engineer in an office, I felt like I lost the chief thing in my life, and felt like I couldn’t live without art and this was really interesting for me because I thought I was only making music because I knew how to, but when I stopped making music, I thought, “Wow, that’s it, I cannot live anymore, because I don’t know who I am.” I needed to do something, but in this situation, when you hear missile attacks every night, it is very hard. In my case, I also know what is happening on the frontline because of my job with the military, and this, of course, is depressing.

That is why I decided to make very simple music that anyone could understand, and I wanted it to be about our pain and about what is going on and the reality of life. So I took my guitar, and all my gear from the institute, my synthesizer, and consoles and took everything home. I had all my stuff on the floor, an electric guitar, an acoustic guitar and the bayan, and the accordion. The album Hypogonadism was made only with guitar, bayan and some synthesizers, but mostly guitar and bayan.

Wow, ok. There are also a couple of samples from Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors.

Yes, Parajanov. I don’t know why. Just because it is a really amazing movie. His life and destiny was really hard because he was imprisoned by the Soviet Union. He made the film in the Ukrainian language which was forbidden. The authorities did everything in their power to make you believe that it didn’t exist anymore or that it was just the language of villagers, but everybody knows the truth now.

You know, one of my recurrent questions for UFN is what book, film, album etc. best represents Ukraine for my interviewees and I’d say that maybe 80% pick that film.

Interesting.

To me, that’s a good film, and I love Parajanov, but there are more recent Ukrainian films I also find outstanding, like last night I was watching Atlantis.

Amazing film.

But most people pick Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors as the one classic that they can turn to.

Yes, because it’s the most Ukrainian film, because it is authentic with its madness and it’s hard, and musically poetic and that represents Ukraine for me.

What are the samples you used from the film?

Some sounds of trembeat, because I like that instrument, and also some snippets of conversation about the molfar [A molfar (Ukrainian: мольфа́р) is a person with purported magical abilities in Hutsul culture. Their abilities focus on herbalism and other folk magic].

Ok, and why the title, Hypogonadism?

It’s an homage from the Second World War when there was a song about Hitler who had only one testicle [hums the tune]. And, I don’t know, it was just funny to imagine that Putin has only one testicle. Hypogonadism is not actually that funny because it is an illness where someone doesn’t have testicles. The cover art was made by Liosha Say, I like it, it’s a very nice project.

Ok, can we talk about Metanoia now?

That was just the music that came to me. Once again, after Hypogonadism, I had some time when I didn’t make any music, but I always have to do something with Max MSP. When I have 50 minutes or one hour, I just open my laptop and make a new patch and of course every new patch gives you a new sound. That is why I like Max MPS, because you have an idea and then you develop a patch and during this development you have a lot of sounds, and you record everything that is going on. So, after the development of a patch I have a lot of samples, some strange material that I put inside some DAW program and sculpt this sound. This is how I made Metanoia, but I made a lot of music and this is only the first part of it. I have the second part of Metanoia already completed with even one track with Parajanov once again. It goes from Hypogonadism to Metanoia. So, I think the next album will be Metanoia 2 because it has already been one year since I released the first one. I just sent it to Dyma Kotra and he said, “Nice, let’s do this album.”

Actually, now I also prepared another album, it will be a full LP which is now in production [Postulate]. I have already been waiting for half a year for it come out on vinyl and I decided to connect different styles like IDM breakbeat and hardcore, so it’s like Squarepusher meets Korn because hardcore music is the first music I played when I was in my 20s. Squarepusher was amazing for me, this strange album, I will play it in June. It is much more understandable, because all the Max MSP or the electroacoustic music I make is not for everyone, but this is like 50% pop music, of course it’s not pop music, but IDM and it is not hard to listen.

Was there a specific concept that you wanted to develop with Metanoia?

Was there a specific concept that you wanted to develop with Metanoia?

It’s not about a concept, it is much more about technical… You know, Kotra said about my work that I try to take a cold program like Max MSP, which is just code, and I try to install life. That is why it sounds really strange even for me, it’s like dead code but with emotion and that is what I like about it. 32

For me it was always the question of why Aphex Twin was so popular because I know a lot of musicians, especially now, who make music, which is almost the same, but they are not famous and so on. I know it’s because it is much more simple now to make music than it was in the 90s when Aphex Twin started. But the true thing is about the spirit, about the soul of the musician that goes into the music. And Authecre is another example of guys who work with dead code, but each track, when you listen to it, you understand that is has soul. And that’s the case with Metanoia, I think. You can feel the emotion and that it is about pain. Metanoia is about asking for forgiveness and getting this feeling that you are forgiven. During all this time I thought a lot about my friends from russia, about my best friends from school, my mother, my sister, they are all there and I don’t speak to them, and it was interesting to me to imagine what they think now about the whole situation and about this feeling of forgiveness. Maybe they understand that nobody will forgive them. It is impossible.

You know, when I was in Moscow, it was the time of Chechnya, and I was so stupid really, I thought, war is bad, but I did nothing. I was 16-17 so I did nothing, I didn’t say anything. I only started to demonstrate against the government of russia when I was 21-22 and then I left the country.

Sorry, if I may ask, how do you feel about the idea of the so-called “good Russian”?

Of course it is bullshit, absolute bullshit, because you know, when you are a soldier, or you work with soldiers like we do in our office, we have this kind of black humour, and we just say, a good russian is a dead russian. And when we see the dead body of a russian we say, “Oh, a good russian,” something like this.

It all depends on what this good russian did to be a good russian. If you just escaped the country and you live in Europe and say, “I am against the war, Putin is bad, etc.” That’s not being a good russian. You are just thinking of your own comfort if you live in Europe.

You know, I had the opportunity of leaving the country and going to Europe, because I don’t have a Ukrainian passport, but I decided to stay here because my friends are here, and we want to fight against this invasion. I think maybe I am a good russian in this case, because I am here and I am doing my best. I thought maybe I should go to the frontline but after speaking to my friends we decided that since se have such a good company, it is more useful to be a good engineer here than just a good soldier on the frontline. But we still go to the frontline, we speak to soldiers and try out what we have been developing. So, to answer your question, it depends on who you call a good russian.

Can I ask you about the track “The Population of Bakhumt”? Since the full-scale invasion there have been a number of tracks and compositions within contemporary music about cities like Mariupol and Bucha, such as “Bucha Lacrimosa,” etc. How do you feel about this and about tackling such subjects and what was your own approach?

You know, I try to avoid simplistic ideas, like “this is good,” or “this is bad.” That is why I try to make some code starting with the title of the album and tracks and so on. As the war goes on one would assume that people would understand what is going on, but then they don’t and you keep having to repeat, “this is bad,” “look at this.” Unfortunately, it becomes a necessity. I would like the information to be more shaded and for people to work out the meaning. I have a lot of issues with music that uses triggers like sirens for instance. At the beginning everyone was doing this. It is naïve, and I don’t like it.

You know, I don’t even remember the titles of the tracks from Metanoia, but they are not that direct, sometimes they do point to something specific but not always. “The Population of Bakhmut” was meant to be tragically ironic, because the population of Bakhmut is zero. I thought it would be interesting if someone from another country would google “what is the population of Bakhmut?” and would find out that this city no longer exists.

Ok, so I was just looking at the other titles of the tracks.

“Lost in Transition” is the name of this snowboard movie because in another part of my life I am a snowboarder, and I remember it was an amazing film.

“A Whole Revolution”, “Digital Battlefields”, “Lament of the Peacemaker”, “Budding Dub”, “The Population of Bakhmut”… And of course, “I am not interested in politics” is ironic about russians.

Ok, could you talk a bit more about the music itself. You seem to give great importance to space in your work, and I am thinking as well as the album you released at the time of the full-scale invasion, Ter.rain which was centred on urban landscapes. How important would you say is space within your acoustic world?

Ok, could you talk a bit more about the music itself. You seem to give great importance to space in your work, and I am thinking as well as the album you released at the time of the full-scale invasion, Ter.rain which was centred on urban landscapes. How important would you say is space within your acoustic world?

Yes, it is important, but actually I cannot analyse what I am doing because it is just a feeling, it is more intuitive for me. But you should understand that when I work with Alla Zahaikevych, I use ambisonic systems, multichannel systems and so on. I have many works with 8 or 12 channels. For instance, I made work for 12 accordions. The idea was to put all the musicians in a circle around the audience, so it is like ambisonics but analogue, without electronics. They had scores and they played. It means that I work with space every time and how I work depends on the material. I can work with classic musicians, or electronic music or generative music like Max MSP or even just synthesizers, like when I go for simple powerful noise IDM music, but I still use some kind of knowledge of space. And when I perform my setup, I build it so that I can switch to four or even eight channels.

If this is what you mean by space, then this is my answer, but there is another idea of space and that is emotional space and that is a completely different thing. Sometimes when you listen to music you listen to the person who made the music, and sometime you listen to yourself in music. I like it when it is not so important who made the music because you find yourself inside the sound. This person has given you space for yourself. This is the case, for example, in some piano pieces by John Cage, it’s simple, minimalistic music with a lot of space in-between. It’s very interesting. Or Brian Eno with Music for Airports.

Ok, let’s talk about Silvestrov now and the album Landscapes of Silvestrov.

Ah, yes. Ok, it was very simple. I have worked with Alla for a long time, but I never made music with her. She has her own way, I have mine, and we never thought we could connect our ways and meet somewhere. I used to make Max MSP patches for her and her opera Vyshyvanyi. King of Ukraine which was performed in Kharkiv in 2021, for example. I made complex patches for real time generative process for musicians to make these sound effects in real time we used multichannel.

Then she asked me if I wanted to create some music together for the Bouquet Festival in summer 2022. We got our friend Lisa on Bandura and we took Silvestrov and thought what is special about his music is that it is music about emotions and about the landscape. Alla can speak better about this as she is a classical musician, but she said this music is about art, wind, sea, water and she said, “Ok let’s make this a 40 minute piece that would be like a journey through the earth in the vision of Silvestrov.” So I made some Max MSP patches, she gave me some scores from Silvestrov, and I used them to generate some soundscape and music. I then made another patch to make these real time effects for Lisa on bandura, I cut what she was playing into little pieces, like granules and I started working with sand or wind, and so on and we played it live. When we listened back to the music we thought, “This is interesting, maybe we should make an album.” We gave it it to another friend of ours who is an engineer and he put it inside an ambisonic system and you can now listen to it on apple music.

I actually talked to Alla last year, and she was critical of Silvestrov, she likes very much early Silvestrov, but is more critical or his more recent stuff.

It’s pop music!

So, I was surprised when I saw the album. Did you actually take the scores from Silvestrov then, and which ones did you work on?

Yes, Alla gave them to me, but I used the atonal music, not the harmonic stuff. And I understand why Alla says this, because she is an avant-garde musician and she loves this period of music and she feels like it is “зрада”… how to translate in English… like a betrayal for musicians such as Silvestrov who made really cool avant-garde music in the 60s and who then moved to simpler and more understandable music. Alla still goes her own way, the way of French spectral music, but sometimes she still makes music for movies, which is more classical.

Are there any works from the past three and half years that you feel have captured this situation and give a sense of current events?

Are there any works from the past three and half years that you feel have captured this situation and give a sense of current events?

It’s a difficult question because I don’t listen to music. I can listen to very simple music from the 00s, or music from my youth like Korn.

Recently, I was listening to all this “no name” music on Spotify, people with like 20 listeners and I thought wow, it’s really cool. Amazing music, professional and nicely made, but when I try to find something Ukrainian, I haven’t heard anything that catches me on an emotional level as yet, but maybe I need to listen to more Ukrainian music. I am very critical and I am very critical of my own music as well.

Have you performed at нойз щосереди [Noise Every Wednesday]?

No, it’s funny because I thought it was just noise. They asked me to play and I said, “Sorry, I don’t play noise,” and they said, “But it is not just about noise.” I don’t understand, why is it called Noise Every Wednesday then? So, we had a little misunderstanding. For me, noise music is Merzbow or something like this. But when you say everything is noise then it’s funny.

I think it is more about giving people a platform to experiment.

Yes, but it is not about noise music. With Kotra we were joking that one day someone will start a course of noise music, “We will teach you how to take a microphone and smash it on a snare with blood!”

Is there anything else you want to add?

No, I think I already said too much. I hope the war will end. And fuck Putin. That’s all.

Are you optimistic, pessimistic or realistic?

I am bipolar, optimistic-pessimistic, but you know we are tired and if you live here you will understand.

[The interview was edited for length and clarity]

MAY 29, 2025 – KYIV

Oleksandr Ostrovskyi and Tetiana Novytska – The Claquers

Oleksandr Ostrovskiy: We are Oleksandr and Tetiana and both of us are part of The Claquers, media about classical music in Ukraine and Ukrainian music abroad. I am a co-founder of this media from 2020 and Tatiana is editor in chief from March 2024.

So, is she your boss?

OO: No, it’s more horizontal.

Is it a democratic structure?

Tetiana Novytska: It’s a very friendly and democratic team.

OO: We try to manage things together but of course many of the tasks are on the shoulder of Tanya but we try to help when we cantogether with colleagues like Liza Sirenko and Dzvenyslava Safian. But since our founder Stas Nevmerzhytskyi mobilised in March of last year, Tetiana took on the role of editor in chief.

When you say Stas mobilised and joined the army, if this is not too personal a question, but has he joined cultural forces?

OO: It would be better to ask Stas, but no, he joined the fighting forces.

Before we get into the specifics of the Claquers, can you describe where we are?

OO: We are in Podil in the newest area called Vozdvizhenka with big ugly buildings in a mock baroque style that were built in the late 2000s. There are a lot of flats for the rich.

So, is this a posh part of Podil?

OO: Yes, but many of these flats are still empty, so it was like a ghost district for a long time. Now we have some offices on the ground floors, and some coffee shops.

Describe this coffee shop where we are sitting right now.

OO: Tea G Spot is not a coffee shop, it only serves tea from different parts of the world, but they also serve them in the style of coffee drinks, like espresso, latte…

So an espresso is made with an espresso machine but it is actually a shot of tea?

OO: Yes. But they use a special machine for making this espresso tea. I like this place because it is quiet. This is not a very popular district but you can find cosy places and one can work here and drink tea.

Ok, back to the Claquers, how long has it been in existence?

TN: We will celebrate five years on June 11.

OO: The site was founded in 2020, but our team formed in Autumn of 2019. It started off with the communication team of Kyiv music fest. Stas was the head of the communication team and he offered to write different articles, critical reviews and previews of the concerts at the Kyiv Music Fest. We decided then that we should be a team as we realised that we didn’t have great coverage of such concerts and different events in Kyiv, so this work was useful to us first of all. In Lviv they already had such media, the website Moderato, but there was nothing of the kind in Kyiv. Of course there were critics from Kyiv writing for Moderato, but we wanted to expand such coverage.

Ok, for those who don’t know, could you explain what Moderato is?

OO: Moderato was a critical media about different classical music events founded in Lviv by…

TN: The musicologist Stefaniia Oliynyk as a personal endeavour.

OO: She ran it on her own, which can be a problem because one doesn’t have a team to rely on and there are not enough resources. So, unfortunately, Moderato closed and now one cannot even find it on the Internet as the domain was lost after Stefaniia became the communications manager first at Lviv Opera, then at the Krushelnytska Museum, and after that at the Zankovetskaya Museum. She just didn’t have the necessary resources to manage the site. It was a very good project though and our first texts were published there.

Let’s talk figures, how is The Claquers structures in terms of editorial content, how many articles do you publish?

TN: Now our work has changed because we can no longer publish as many texts as we used to at the beginning of The Claquers. We currently publish I think two-three texts per week. They now tend to be more analytical articles, and more explainers about a composer or about some particular work or project in Ukraine. We don’t publish as many news items, and not as many critical reviews but we have a lot of analytical texts and interviews. We still do have reviews but we don’t have the resources…

OO: I think it’s no longer the main aim now because if you write reviews of events made under bombs in shelters and you know how people made them, this is great and you should explain why it is great, but it is not really about how well a piece was played. The reviews would be about making a good project under the circumstances. “Of course, it couldn’t be so good but…” So, I think analytical reviews that take into account the context of present times are more important than just a description of news and facts.

TN: And now we have more and more articles about different social topics. Last month we published a text about Ukrainian musicians in captivity, the second large article on the subject. We wrote about members of Ukrainian orchestras who have been in captivity for over three years now.

Also, there are many articles about musicians who joined the army, about the fallen ones and those on the frontlines. Next week we should have an article on Olena Kohut, the Ukrainian organist killed by russians in Sumy back in April. It is important to talk about this. And we also translate these articles into English. That might even be the most important thing we do, to communicate with the world at present times and give the Ukrainian context.

So, The Claquers is not just about promoting Ukrainian culture but also about giving the full picture and providing the context into which works are produced and performed?

OO: At least we are trying.

I believe it is fair to say that you have a lot of catching up to do, as Russia has been very good at promoting their own culture for centuries, how do you even begin to educate the general public and introduce Ukrainian composers the them?

OO: We are not an educational media, I prefer to say that we try to explain things. We aim to produce texts that are readable but not simplistic. There are many articles in different scientific journals about Ukrainian music and musicologists write texts, but it could be hard to read with scientific jargon, but I think…

TN: We are “popular scientific.”

OO: Yeah. Popular science, we try to explain better. Of course we cannot rely on the same funding that russian outlets benefit from, and we cannot compete with the promotion of russian culture in the world. Still, we don’t have a choice but to speak, even for ourselves because many of us have lived within this russian context for a very long time. We read these books, we listened to that music, back at a time when it was ok to have russian text books in our conservatory with no Ukrainian translations.

TN: There were special courses on russian music in music academies and colleges.

OO: We should explain for ourselves first and foremost that Ukrainian culture is not second rate and is not outdated. It’s not the case that russian culture is big and Ukrainian is small. Even for myself, I have discovered new names and works thanks to articles to The Claquers.

Ok, on the topic of education, so you had music classes in school and studied mostly Russian composers? And how aware were you of your Ukrainian musical heritage?

TN: The music education system before the full-scale invasion, required us to study European classical music, a separate course in russian music, and a separate course in Ukrainian music. At the same time, contemporary music was not actually taught in music schools and colleges…

OO: You know, when I was studying in music college, I thought that the year Shostakovich died, 1975, was the end of classical music. I remember thinking what a pity it was that Shostakovich had died!

We studied on Soviet books from the 80s, and the 70s were the last chapter.

The Nota Bene chamber ensamble of Kyiv

TN: In the last year of the music college, we studied Soviet music (according to the quota of foreign music, obviously). The manual I studied on (also Soviet, as you might guess) ended with the death of Khachaturian [1978], so that for me was the end of classical music. But anyway, in the music academy we had no choice but to study russian music, from the Middle Ages to modern times. But now, the education system is transforming. Also, it needs to be said, that while we did cover classical music from Ukraine, russian music always commandeered a place or prominence even in independent Ukraine.

OO: That was in your department in the conservatory. I was studying at the culturology department, and we didn’t have a specific course on russian music even in 2015. We had a course on Eastern European music, and of course the biggest part of it was dedicated to russian composers, but we also covered Polish music and… that’s it! (laughs). Maybe even Czech music.

Also, we had two special courses on Ukrainian music. I had good courses from Vitaly Vyshinsky, a Ukrainian composer and musicologist, about Ukrainian music. It was really useful. I can say I had a more balanced musical education.

TN: Yes, we also had this course, but we still had this special course on russian music in 2022, but after the beginning of the full-scale invasion we decided no longer to study russian music.

OO: It needs also to be said that the greatest number of books are on russian music. We only have one textbook about Ukrainian music by Lidiia Korniy and Bohdan Siuta published in 2014. That is a problem because one can find a lot of information about russian music, whereas there is only one textbook for Ukrainian music other than articles in scientific journals. This means that The Claquers is also used as a valuable source of information on Ukrainian music.

TN: And that is why it is important to write more analytical texts.

OO: Yeah, it’s also about the ecosystem. We didn’t have one, and we should be a part of it, and build it from the beginning. I am not saying we are like messiahs, but we should be a part of this. It is also very cool that two weeks after coming back from Paris [Ostrovskyi and Novytska took part in the international conference Ukrainian Music Beyond Borders at the Sorbonne University in Paris on 24-25 April 2025], a new media was launched. They already promised to write more about Ukrainian music. The more the better.

What is this new media?

OO: Huck.

Ok, back to the Claquers. What can you tell us about the makeup of your team?

TN: We invite young musicologists who study at music academies from Kyiv, Lviv, Kharkiv… to contribute. The biggest part of our authors are young musicology students and our teachers.

OO: Colleagues! You have already graduated.

TN: We have maybe 15-20 authors, but we are all freelancers, us included. We all have different day jobs. So, authors might write an article every three or four months, but they are all highly motivated. They studied as musicologists and normally write scientific articles, but it is cool when they can write accessible articles on their specialised subjects.

Maybe two weeks ago we published a text about Crimean Tatar music written by a specialist on the subject. So, our collaboration is maybe sporadic with some authors…

OO: But they know their topics and they can write about them. It is difficult to find people to write about Crimean Tatar music, for instance, but Anton [surname and link to his article?] did all this research and knows where to find the necessary information, so that one cand find everything in one article.

TN: And these articles can be of really high quality because our contributors are experts on such topics.

And who is reading The Claquers?

TN: The largest part of our audience is in Ukraine, but we also have readers in other European countries, the US and Japan. So, who is our reader? I believe young people interested in classical music with music education who want to learn more about Ukrainian culture. We have different articles that can be interesting for a different target audience. They can be useful for students, for teachers. We try to write the articles in a simpler way for a large audience.

OO: The audience can be different, and our analytical articles can be interesting for students and teachers alike, but social pieces about Ukrainian musicians in captivity, or about banning russian music…

Sorry to interrupt but on the subject of cancelling Russian culture, has your position changed over time? I am asking because at the Lviv media forum some were saying that since calls to cancel Russian culture seem to be increasingly falling on deaf ears, new strategies should be put in place.

OO: That was being said about cancelling russian culture abroad. In Ukraine, russian culture is cancelled without questions, because our own identity is at stake…

TN: And our very existence.

OO: Yes. We cannot promote russian culture in Ukraine. Of course we cannot fight against the windmills in Europe like Don Quixote, but we should concentrate on our own culture which is a matter of survival for us.

Absolutely, but on the international stage, is the message really getting through or shouldn’t you be rethinking your strategy?

OO: You know, at the beginning of the full-scale invasion we banned all the musicians who performed russian music and who played concerts with Russian musicians. We decided we shouldn’t write about them.

The Claquers is a space for Ukrainian music and Ukrainian musicians. We want to shine the spotlight on Ukrainian music. And if you are a Ukrainian artist playing russian music abroad, we don’t want to know, that’s your choice. No one can prevent you from doing that, but it’s an ethical choice at the end of the day.

We stated our position right at the end of February 2022 at the beginning of the full-scale invasion that we wouldn’t cover such musicians, and we even took down some articles about musicians who later performed Russian music or performed with Russian musicians. We cannot promote them.

TN: Also, after the russian full-scale invasion we had some articles about russian music through the lens of postcolonial discourse. We wrote about Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, and about Glinka. We wrote about Tchaikovsky because the music academy in Kyiv is still named after Tchaikovsky which is a problem.

OO: That article was very at the end of 2022 because of very public discussion on whether one should consider Tchaikovsky a russian or a Ukrainian composer and there were many manipulative discussion about his Ukrainian roots and the Ukrainian themes in his work and so on and so forth, so we decided to write this long read that was published only in Ukrainian because it was an internal discussion we were having. I went to the archives and registry offices to find the birth certificates. Back in 1940, on the centenary of Tchaikovsky, they published books about the unity of Ukraine and russian and their cultural tradition at a time when the Soviet Union was already involved in WWII. The article I wrote was designed to dispel this myth. And now, many publications and people refer to this text. Is this still relevant? Yes.

Let us talk about works composed after the full-scale invasion, have many composers been addressing current events?

TN: Talking about concrete works, we had Yevhen Stankovych’s “Psalms of War”; Victoria Poleva with “Bucha Lacrimosa”; Svyatoslav Lunyov with “Post”; Zoltan Almashi’s “Maria’s City”…

OO: I’m traying to remember if some of them chose escapism in music as well. Because I think that escapism in art could also be a valid choice to distract us from the anxiety and the troubles.

We don’t have to put all of our experiences in art. The bigger problem is to avoid putting what is not your direct experience in art. I think it is strange if you speak about someone else in your own words, It is ok if you are reflecting on what you might have seen on the news as a therapy for yourself, but if you try to speak as a defender or soldier in culture without having been on the frontline or even heard explosions, that is not your own experience. One could claim they are giving voice to those who no longer have a voice, like dead soldiers, and their stories should be heard, but it is not ok if you speak for them and put yourself in their shoes because it is not your experience, you cannot understand them even if you try.

TN: There are cases when you can explain the situation to a European audience and this can work, but in Ukraine, approaching certain topics can be retraumatising.

OO: From the very beginning of the full-scale war many composers tried to use air raid sirens played on violin or electroacoustic instruments and such pieces were intended to make foreign audiences hear the sounds that we hear every day. But when you perform these pieces in Ukraine if people hear a siren they might wonder whether this is part of the piece or a real siren. This is not ok because it is our everyday experience, we shouldn’t have to listen to this in music.

TN: And let us not forget we were all scared by the loud thunder today so…

Are you also saying that Ukrainian composers who live abroad and have no direct experience of the invasion maybe should not be writing music about the war, because they have not experienced it first hand?

OO: It depends. It is also about timing. In 2022 many composers who went abroad already had this experience and they used it in their work. But when you have been abroad for three and a half years without visiting Ukraine, you have more in common with foreign people than Ukrainians. That said, even within Ukrainepeople have different experiences.

We have regions that are more sheltered. They can also be dangerous because in Lviv for example there was a family killed and one cannot be safe even there, but when you hear drones on a daily basis that is another experience; when you live on the frontline, that is also another experience; when you are in the army, that is a further experience. There are a lot of different experiences, and, unfortunately, it is hard to understand each other. But we should speak to each other and find some common ground and be helpful to one another.

TN: Also, I want to mention Roman Grygoriv who released the album Irrenaissance last year, with music played using the shell of an Uragan MLRS cluster munition missile. It’s electroacoustic music and he presented this work at the EU parliament as a political statement addressed to European society and I believe it works.

OO: Yes, but the missile was launched on Kyiv and he lives in Kyiv so he is talking about his own experience.

I am also interested in the idea of the landscape and how contaminated this has become in Ukraine because of the war. This is a favoured topic in the visual arts as well and I wanted to have an idea if this translates into classical music. Also, has there been an increase in works that reference particular regional music? I was also thinking of Landscapes of Silvestrov for instance.

OO: We can talk about Gaia 24 and Opera del mondo by Roman Grygoriv and Illia Razumeiko which is about the Khakovka damn catastrophe. Razumeiko is from Nikopol, so this is personal for him.

TN: They also made CHORNOBYLDORF about the fallout from the Chornobyl nuclear power.

OO: Yes, but that was before the full-scale invasion.

I also wanted to get an idea if there is an increase in the use of traditional themes from specific regions, like for instance Tchaikovsky used traditional tunes from Ukraine…

OO: You know, this has always been common in Ukraine from the times of Lysenko, he used these specific themes and made works like folk and it was very common.

Is it common now?

OO: It is hard to say. Also, if you want to use a folk song and use it as sharovarshchyna [a culturological and journalistic term, usually negative, for the ethnic stereotype of Ukrainian culture through pseudo-folk] this is not ok …

TN: Oleksandr Nestorov wrote a piece at the end of the 90s called Irradiated Sounds, an electro acoustic album where he used folk songs from Chornobyl performed by the folk group Drevo, a folk group specialising in folk singing from different regions because Polyssia and Slobozhanshchyna for instance have different traditions of singing, and these are mixed with electroacoustic.

Ok, anything else we should mention?

OO: We should mention the Shevchenko Scientific Society. It is thanks to their grant that we can keep the site alive. We also have a team of patrons who make donations and are a big part of the equation.

[The interview was edited for length and clarity]

MAY 30, 2025 – KYIV

Oleksii Podat

My name is Oleksiy Podat. I live in Kyiv. I was born in the Donetsk region in Sloviansk, which is now on the frontline.

My name is Oleksiy Podat. I live in Kyiv. I was born in the Donetsk region in Sloviansk, which is now on the frontline.

Did you have a musical education?

Kind of. You know, it was really weird. I did not go to musical school or anything like that, but in my regular school there was a class with in-depth musical education. We had like four lessons of music a week instead of one. So yeah, we learned how to play sopilka, learned some drumming, and arpeggio, and stuff like that.

So you can read music?

I kind of can, but it’s all very… it was very basic.

Most of the time we listened to classical stuff. Like we sat and listened. Or there were lessons where we could bring our… not the music that we produced, but the music we liked to the class, and everyone shared what they listened to. And it was age of, uh, CDs, CD discs, CD players. So, everyone brought their CDs from home and took it to the lesson.

What kind of music are we talking about?

I brought the album Crazy Frog’s Best Hits. I played the intro because it’s really great melodic-wise. I think it’s still super for me. Other people brought some rap music, some, rock stuff, and Soviet stuff. You know, that was back in 2002.

Okay. The first thing is, how come you don’t have a moniker?

Like why I didn’t choose some project name?

Yeah.

Okay, basically when I started making electronic music, I was like 14, 15 years old. And since then, I’ve changed like, three or four (laughs) different monikers. And basically, like in 2019, I guess, I thought that the best way to name my project was just my name as I don’t want to stick to the idea that if my taste in genre changes, then I have to do another project and name it another way.

I’m just a person who lives his own life, and life is changing, and tastes are changing. It’s all right to release and to perform under my real name because it’s more convenient and I already have a name, so yeah, I am going to use it, and I like my name. Before that I had different monikers which translated into English would be something like World Championship of Meditation and different other ones. This was kind of a joke because it’s kind of absurd. But I have been Oleksii Podat for six years now, I guess. And for 28 years of my life also.

I was talking to Zhenia [Skripnik] yesterday and we were talking about Sloviansk. Could you just give me your own view of Sloviansk and what life was like for you back then?

Usually when I talk about Sloviansk to foreigners, I say that it’s a wonderful city. But it’s kind of difficult to tell my story from this perspective so I will be honest. At the time when I grew up the city was kind of all right, but there were no or little activities for the youth. So it was kind of dull. You had choice to fuck around like go and drink in the city and so on, or to be like addicted to some computer stuff and social media. Or you found yourself some interest in, I don’t know, FL [Fruity Loops], Ableton, and so on, because there was not much to do in the city.

Were there any music venues?

Were there any music venues?

Uh, of course, yeah, there were, but, um… but, but, but, but… there were kind of like some venues in bars, restaurants, you know, something like that.

The biggest one was in the main square of the city. The biggest celebrations were on the anniversay of the liberation of the city from the Nazis which in Sloviansk is in September when Ukrainian stars would perform in the main square in front of a many people. But there was no such thing as a scene before Zhenia started Shum Rave. I didn’t hear of any activities regarding electronic music or instrumental music which could be regular and interesting at the time before Shum Rave.

I liked being raised in small town because it motivated me to leave very fast and not to remain stuck in one city with my parents, which is very important. And yeah, there were not a lot of activities for students, and I just wanted to go away and travel throughout Ukraine. So in August of 2014 I moved to Kharkiv and lived there for 8 years.

Sorry if I ask this, but did you move to Kharkiv because of the situation?

No. Okay, the invasion of Sloviansk by russian troops happened on the 12th of April 2014. At the time I was graduating from school, and I lived under occupation for two, three months before we left for Kyiv, so I could pass my finals and apply to university. But while I was in Kyiv on maybe the 5th of July or the 5th of August, I don’t remember, the city was liberated. Ukraine forces retook the town and liberated Kramatorsk, Sloviansk and other cities.

I moved to Kharkiv when I started collage just to live in another city and not be with my parents. I mean, they are good people, but I like to be less controlled in my life.

What did you study?

I have a master’s degree in political science from Kharkiv University. I studied political sciene because when I was thinking about what I wanted to do, I looked at all the options, like any profession I could be interested in and the only one was political science.

I watched a lot of movies, films, TV shows about politics, Ukrainian and worldwide, and I liked the news as a kid. So, I don’t know, it was like a no-brainer for me.

What about music?

Music is, I suppose… a medium through which I can understand myself more. I just use it to process some emotions or some thoughts that I have been experiencing for some time and when I do it through music, I can understand myself more, not on a verbal level but more in some emotional space or something like that.

And have you always been interested in electronic music or were you like a punk kid playing in bands or…

I went through different phases in my life, but I was a punk kid playing in one band like for two months. It didn’t go well. When I was 13, I was kind of a DJ. I made mixtapes and sent them to independent radio stations and the mixes consisted of trance music and after that I got into Thom Yorke, Radiohead and some electronic stuff like Q Day. At 14-15 Radiohead just turned my vision of how music can be made and after that there was Modeselektor, Aphex Twin, James Holden and some other stuff. So, basically, yes, I was always interested in electronic music for as long as I can remember, but that was not common in my city. The majority listened to rap, maybe some house like David Guetta or something like that, but it was not common in my area. The Internet helped a lot at the time.

we’ll just do it again

So are you self-taught in electronic music?

Yeah.

What kind of programs did you use?

Uh, when I was 13, I was deejaying and I thought it would be great to create something myself, so I downloaded FL Studio. I didn’t understand shit like at all, so I thought music production is not for me, but one year later I randomly downloaded Ableton, and it was much easier for me and…

Really?

Yeah, because there were different modes where you could see the real structure of a track and the arrangement mode in Ableton really helped me to understand how everything assembles into a composition. So, yeah, it was much easier for me, and yeah, it was Ableton when I was 14-15. I started my vaporwave project at the time, but it basically helped me to understand how to play with structure. I didn’t have a powerful computer, so I wasn’t using some of the plugins and instead of that I recorded the sounds of the city and of people talking on an audio recorder, or on the phone, and I imported those sounds and used tiny fragments to create drums, bass, other instruments synth, just from the recordings and it helped me a lot because my computer couldn’t handle plugins so yeah, I found my own way of doing music within certain limitations.

Has the full-scale invasion changed your production process?

If we talk about process in terms of emotional space and readiness to do something, yes, it affected me. But technically not a lot of has changed. Things changed in terms of the time I can spend making music because I am involved in some war related activities. Also, I would say that all external events affect my music on an emotional level, but in terms of the technique it hasn’t changed.

But now you work with plugins or are you still taking field recordings?

I would say 50-50. For plugins I use effects like reverb, delay and so on but most of the time I use Ableton’s built in plugins or synthesizers and the other 50% are my field recordings which I transform into instruments. I like to keep the balance. It’s more interesting for me, rather than stick to one method. Now my computer is fine, it can handle synths like Serum or Omnisphere but I am more comfortable with simple things that are limited because I often find inspiration with limited possibilities.

Many musicians have told me that they in the immediate aftermath of the full-scale invasion they couldn’t even listen to music let alone produce anything new. Is your experience similar?

My experience with the war started in 2014. So, I think that this allowed me to start my creative process straight away after the invasion. The first track I created was in the end of March 2022, which is pretty quick.

my mom sends me photos from relatively safe places

Sorry, was that “my mom sends me photos from relatively safe places”?

Yeah, yeah, yeah. That is an EP with two different versions of the track.