Blue Bull by Mariia Prymachenko

Whenever I start a new episode of Ukrainian Field Notes, I have no idea where it will take me. This month I ended with 21 interviews (15 male and 9 female – some of the interviews are with bands). Among these, there are 4 active servicemen and 1 veteran. It all makes for 35,000+ words. It might sound trite, but I am always grateful to those who share their stories.

In Kyiv we talk Barbie with Chloё Landau; in Cherkasy we ponder about failed experiments with Zaviruga; Helena Atkin and Daria Titova discuss storytelling between London and Estonia; in Bila Tserkva, lebben tries not to write about war; on the frontline, adm:t appreciates every second of creativity while Remez reassures us that no one has cancelled AC/DC or Johnny Cash.

Further afield, in Finland, Yevgen Chebotarenko picks a sexy cover for his album; in Poland, Volodymyr Ponikarovsky trusts actions only; Renata Kazhan goes for a minimal setupin Helsinki; Sharko mourns his cat in Czechia; in Kyiv Embrion Bormana is not ready to return to studio work, whereas cybermykola, a Pavlohrad native, admits to not having seen himself as artist to begin with.

Moving across the ocean, Ro Rouseeau reminisces on post-Euromaidan Kyiv; back in Cherkasy, Tryastya goes full on rave; in Rzhyshchiv, Høstvind expresses his dislike for streaming services; in Berlin NASTYA NVRSLP literally never sleeps; in Lviv, екскременти picks up the harmonica; in Kyiv, mariia&magdalyna ask what the fuck is wrong with this world? In Kyiv, Ksenia Yanus and Vadym Oliinykov from noizshchoseredy explain why Wednesdays have gone silent; and finally, Ambiotik invites us for a session of music therapy in Kalush.

Olha and JP from Drift Kyiv

In this month’s UFN podcast for Resonance FM we discuss after hours parties and the Ukrainian diaspora with Olha Korovina and JP Doho from Drift Kyiv.

Tracklist:

- Kichi Kazuko – “Battlefield”

- Hasvat Informant – “Touch Brass”

- Vera Logdanidi – “Keep Pushing On”

- TYGAPAW – “Black Trans Masculine Experience” feat. Kings-Lee Rose

- Aniway – “Dead Mouse”

Also, plenty of new releases, including 58918012, Haido, Orfin, Tongi Joi, Paloven, Morphey, екскременти, Ship Her Son, Low Communication, We’ve Already Talked About Th*t, PROLETARSKYI, Koloah, некрохолод, Hidden Element, Weaverbird, Stalkvoid, Pororoka, Delayed Minds, Dirtbag Loris, Dubplanet X, Polje, Monotronique, ummsbiaus, 1914, Bad New from Cosmos, Rebel, Andrey Sirotkin, and Shadow Unit.

In the viewing room, we check out the latest from Latexfauna, Andrii Barmali, DakhaBrakha, Hidden Element, Oi Fusk, Blooms Corda, Ingret, Palindrom, Monokate and хейтспіч.

OCTOBER 19, 2025 – KYIV

photo @hristinazhopa2

I’m a musician based in Kyiv. I love performing in front of an audience—dancing with them and flirting with them. I write songs about what I’m going through or what I’ve been through before. In many of my lyrics, I imagine that I’m already dead. I adore quiet nights, when you can sleep as long as you want. I love wigs and constantly dressing up, I paint my nails with glitter nail polish, I love drawing swans and roses, and I deeply enjoy the feeling of how much agonizing chaos surrounds me.

I started making music about three years ago. I wrote lyrics and tried to sing them or find ways to put them on music. I didn’t know how to use Ableton back then, so I used simple programs I found online and recorded everything on my phone when no one was home.

It wasn’t about an audience—I just wanted to express something, to get it out. Around that time, I also started filming music videos with my ex-girlfriend. They were amateur, but they meant a lot to me emotionally.

Now I’m still doing more or less the same thing, but with better tools. I have a professional microphone at home (it’s pink), and I understand the technical side better. I’ve also started focusing more on live shows. I prepare for each one carefully and try to make it feel like stepping into another world. I don’t want to look polished or perfect on stage—I want to look intense, maybe even a little grotesque. I want to feel like a character from a gruesome fairytale.

photo by @hristinazhopa2

Has the full-scale invasion changed the way you think about music and sound?

It’s difficult for me to answer this question. Since the beginning of the full-scale war, I’ve become more sensitive to loud sounds and more afraid of them. My body reacts instantly to alarming noises like sirens or anything that resembles explosions. This kind of response I notice among the majority of my friends.

Before everything that happened, I used to find those sounds almost poetic — they didn’t cause such strong physical reactions. Because of this shift, I try to be more careful when working with sound, in order not to unintentionally harm others who might have similar sensitivities.

That said, I don’t think my general approach to making music has changed much. The lyrics may have become more complex and less naive, but that’s also a result of growing up. I was 19 when the full-scale war began, and now I feel like my personality has simply become more formed and layered with time.

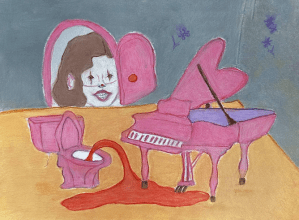

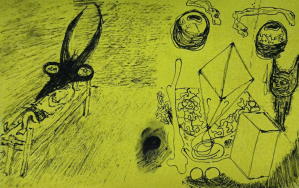

artwork by Chloё Landau

Has your playlist changed in any significant way after the full-scale invasion?

To be honest, since the war began, it has become strangely difficult for me to listen to and process new music. For many months, I found myself looping the same ten tracks over and over — I simply didn’t have the energy to seek out anything new.

I love noise and experimental music, and I’m now surrounded by an incredible number of insanely talented musicians whose live performances I truly enjoy. It feels like I’m slowly starting to “come back to life” and hear again, after several years of silence.

In my teenage years, I used to actively dig for music, often spending half the day searching for something unfamiliar and interesting. I was very into bands like Nurse With Wound, Throbbing Gristle, and Current 93. These days, I enjoy listening to James Ferraro and Pharmakon.

I’ve also become much more selective about what I listen to. It’s extremely important to me that an artist has a clear political stance. I no longer engage with anyone who claims to be “apolitical” or chooses inaction — to me, that reflects weakness and indifference.

artwork by Chloё Landau

You took part in the Construction festival in Dnipro. What can you tell us about that experience and how would you say Construction compares to similar festivals in Ukraine?

I really enjoyed performing at the Konstruktsiya (Construction) festival — the audience was absolutely incredible, and I genuinely had a great time. It was very easy to connect with everyone, and I loved the sense that each person in the crowd felt free to express themselves in their own way.

The festival program was impressively rich and diverse, and it’s especially remarkable that the festival has been held annually since 2014. I’ve grown very fond of Dnipro, and I’m looking forward to the next time I can return there.

I believe that festivals like Konstruktsiya are extremely important for the development of Ukrainian culture. Right now, we have hundreds of incredibly talented musicians who have something meaningful to say. In my opinion, our scene is highly progressive — perhaps even surpassing what we often see abroad.

It seems to me that the war has triggered a powerful shift in our musical landscape and profoundly changed our collective consciousness. Konstruktsiya is without a doubt one of the most unique and compelling phenomena in our current musical world.

Another festival I love and would mention in the same spirit is Fantazery, which also holds a special place in my heart.

photo @supernovwva

You started making music after the full-scale invasion and have released a number of tracks since 2024. How have you managed to be so productive?

In general, my first attempts at making music were back in 2020–2021, but sometime after 2022 I was able to better shape my artistic style and understand more clearly what ideas I want to convey to the crowd. It’s very important for me not to stop and to constantly continue doing my work — it helps me feel like myself.

I remember how during the first 6 months of the war I lived with my friend’s family in a small village in western Germany. There was only a cemetery, an endless forest, and an inactive children’s camp with small wooden playhouses (they were the size of miniature copies of real houses and were painted in all the colors of the rainbow) — I liked to climb in there and record songs on a voice recorder — because for hundreds of meters around there were almost no people and I could finally be alone.

I always try to find an opportunity in my free time to come up with something and record it. Now I still try to constantly do something, although it can be difficult because of full-time work and constant night shelling. This summer, a missile fragment shattered several windows in my apartment while I was at home, and it’s still unsettling to remember that night. But such events only remind me that life is short, and I just try to do more and more.

artwork by Chloё Landau

How is your visual art output connected to your music?

Visuals are a really important part of my art. I love adding photos to go with my music, and I really enjoy coming up with different looks for performances. Also I often draw — my drawings are kind of a visual representation of what’s happening in my songs.

A couple of years ago, I also created designs using 3D dolls, and my friend and I made clothes with those images on them.

With my looks, I want to express fragility and innocence — but with something stirring and a bit unsettling hidden underneath. I like wearing exaggerated doll-like dresses, or costumes from sex shops (like a nurse outfit or a Playboy bunny suit, for example). I love the contrast that creates when combined with my lyrics and music.

I’m drawn to things that are grotesque and theatrical — like I’m Alice in Wonderland, but everything around is destroyed and radioactive, and somehow everyone’s still having fun.

You took part in the Home VA compilation for Klikerklub. Your track was composed in Lviv. How would you define the concept of home and has it changed for you since the full-scale invasion?

The concept of home feels quite blurry for me right now. For the past few years, I’ve been moving around a lot, and most of the time I didn’t feel safe or grounded.

At this point, I have a few places that feel like home in different ways — Chernihiv, where I was born and lived until I was 17; Kyiv, where I’ve been spending most of my time lately; and Lviv, where I stayed for a while at the beginning of the war.

I don’t think home is one specific location — it’s more about having a sense of stability and balance.

I know that for the next few years I want to stay in Ukraine and be part of what’s going on here. The first months of the war were brutal — my family was scattered, and there were days when I honestly didn’t know if they were alive. Now that we’re back together, at least partly, it feels like home is wherever they are.

photo @hristinazhopa2

Have you seen the film Barbie and if so what did you think of it?

I watched Barbie and, honestly, thought it was solid. I’ve had a soft spot for Barbie since I was a kid, and I still enjoy the old animated films and games.

I ended up using samples from the film in a track called Sport Car — it reflects on a destructive period in my life and the feeling of being completely powerless within it.

I wouldn’t call it a masterpiece or something that shifted my perspective. But I do think it’s relevant. Feminism remains a poorly understood topic in our society — people either don’t see the point of it, or assume its goals were achieved decades ago.

In that sense, the film serves a purpose.

I also find myself drawn to exploiting the Barbie image in my own work — partly because it strikes me as a painful, hyper-exaggerated version of the “ideal woman” constructed by the patriarchy. There’s something deeply artificial about it, and I like pushing that absurdity even further.

The image of the blonde with a permanent, soulless smile becomes almost grotesque when taken to its extreme — and that’s exactly what makes it interesting. It’s not just aesthetic; it’s a way to expose how empty and performative that ideal really is.

photo @hristinazhopa2

Are there any works by Ukrainian artists that you feel have captured and conveyed the full-scale invasion and the war experience in a meaningful way for you?

A lot of my friends are artists whose work also deals with the war, and their perspectives mean a lot to me. One of the first names that comes to mind is Illia Todurkin — his work is raw, painful, and incredibly powerful. It really struck me when we met at the beginning of the war.

I’m also deeply moved by Dana Kavelina’s animation. I remember watching one of her films at the Konstruktsiya festival, right before going on stage — and I almost cried. It was that beautiful and that heavy.

Another artist I really value is Kateryna Lysovenko. I love how the bodies in her paintings bleed in this strangely beautiful, almost sacred way — they feel soft and clean, but also disturbing. She captures something very real about motherhood, especially what it means to be a mother during war.

I also think of Tamara Turliun and Krystyna Melnyk – their work has a quiet intensity that sticks with you long after you’ve seen it.

What does being Ukrainian mean for you?

To me, being Ukrainian means being blessed by angels.

Which book / film / album / song / traditional dish / podcast / blog / artwork / building / meme best captures Ukraine for you?

If I had to choose one song that best captures Ukraine, I would pick “Пішла Киця ” by Katya Chilly. As far as I know, it’s a reinterpretation of a traditional Ukrainian lullaby. For some reason, this song always moves me in a way I can’t quite explain — it feels like the most beautiful and mystical thing I’ve heard in months.

I really like this version because it has so much silence, space, and sorrow in it — but also gentleness, protection, and hope. I love that the story is told from a child’s perspective, through something as simple as a tale about a kitten that fell into a well.

I often listen to this track while walking down the street with my headphones on.

OCTOBER 22, 2025 – CHERKASY

завірюга (Zaviruga)

завірюга (Zaviruga)

My name’s Danylo (Daniel). For almost three years, I’ve been running this small but stubborn project called завірюга (zaviruga – blizzard). It all started with a bunch of failed music experiments — different genres, styles, sounds — everything seemed “fine,” but deep down I knew it wasn’t mine. One day, out of pure frustration, I decided to make something that wouldn’t fit any mold — not trendy, not “expected.” That’s how I stumbled into egg-punk. I instantly loved how weird and unapologetic it was.

I’ve been into punk for years, but this time something clicked. In five days, I wrote three tracks for the first single, drew the cover, and even made a video. It felt insane in the best way — like I was laughing at my own chaos. For the first time, it was pure fun.

The war changed everything. It stripped life down to black and white — no grey zones, no pretending. Either you’re honest or you’re not. That’s probably why завірюга sounds the way it does — it’s just me without filters.

You started releasing in 2023 and have been quite prolific. At the same time your longest track is probably 2 minutes 1 second long. What is your production process and what motivates you?

You started releasing in 2023 and have been quite prolific. At the same time your longest track is probably 2 minutes 1 second long. What is your production process and what motivates you?

To be honest, I was hoping no one would ask me about my “creative process,” because it makes me sound lazy as hell. But okay — I work in bursts. I can go months, even a year, doing absolutely nothing. Then suddenly — three songs in three days. I’d love to make more, but if it doesn’t have that same spark, that same honesty as the first one, I’d rather stay quiet.

How would you describe the punk scene in Ukraine and in particular the egg punk scene?

There are some solid punk bands in Ukraine — I listen to a few. Since the full-scale invasion, even more have popped up, which is great. But honestly, most still sound too similar. It’s only a matter of time before some new blood kicks the doors in. As for egg-punk — I haven’t seen anyone else doing it here. Either I’m alone in this corner, or the others are just ghosts on another frequency.

The track “18000” is about Cherkasy. Could you tell us about your relationship to your hometown?

The track “18000” is about Cherkasy. Could you tell us about your relationship to your hometown?

Cherkasy for me is a quiet refuge — a place to walk by the Dnipro, breathe, and reset. I’ve lived in big cities — Kyiv, Kharkiv — loved both, but only here I can actually chill.

How would you describe the music scene in Cherkasy and do you feel part of its community?

The music scene here is small — mostly techno raves now.

What does it mean to you to be Ukrainian?

What does it mean to you to be Ukrainian?

Being Ukrainian is both a curse and a gift. It’s heavy, but real. You see things that break you, and things that make you proud beyond words. I wouldn’t trade it for anything.

Which book / film / album / song / traditional dish / podcast / blog / artwork / building / meme best captures Ukraine for you?

Before the invasion, Ukraine was like the Shire — calm, green, full of small joys. Now it’s Minas Tirith [the capital of Gondor in The Lord of the Rings] — battered but standing tall.

And Rohan — yeah, we’re still waiting for your ride.

OCTOBER 22, 2025 – UK and ESTONIA

Daria: I have a background in Graphic Design and illustration. I’m a passionate embroiderer exploring themes of memory and storytelling. I like to keep a sense of childlike wonder in my work — my pieces often feel like small games or fragments of fairytale worlds. The main character in these worlds is usually a short-haired girl, or sometimes many of them. My connection to music is through Helena; I’m deeply inspired by the way she weaves storytelling into notation — something that feels like a secret language to me, yet an essential tool for her.

Helena: I started as a classical pianist and composer, before being introduced to the contemporary music/arts world during my master’s. I was always super fascinated by scores and the score-writing process, but only started to think about notation as an artistic end in and of itself after being exposed to this more experimental context. Since then, I’ve been interested in the not necessarily musical residue and resonance of the notated score; the way notation ‘unsounds’. My connection to the visual arts (especially embroidery) has, likewise, been hugely inspired by Daria and the beautiful tactility with which she quite literally weaves her stories into existence!

How did a British Estonian composer and a Ukrainian artist come to collaborate, and how do you combine two very different artistic practices?

Helena: We met earlier this year while working on a project run by Narva Art Residency and The British Council in Estonia.

Daria: During the Narva Art Residency, we were asked to lead workshops for children in local Russian-speaking schools, all in Estonian. I think I was selected because I had managed to learn Estonian quite quickly — within a year — and perhaps the organizers thought that might inspire the kids to learn it too.

Helena: We were housed in the same accommodation and so had a real insight into one another’s process and experience of the whole thing – we were simultaneously getting to know each other as artists and as friends, and so the combining of our practices from there on was pretty intuitive.

Daria: I remember seeing Helena “in action” — her gentle and thoughtful way of engaging with the children, guiding them through the workshops, and reflecting on the process afterward. After that residency, I developed a strong interest in co-creation: in giving something creatively, embracing the flow, and letting go of the idea of “this is mine, I am the author.”

Helena: When Daria first reached out with the idea for this project, it felt like a natural continuation of everything that had brought us together in Narva, a majority Russian-speaking city on the Estonia-Russia border that’s been significantly affected by recent reforms to make Estonian-language education compulsory for all. While I’m not Ukrainian, I think our meeting in this context really brought forward the connection felt between Estonia and Ukraine. Our freedoms have been marred by the same occupiers and our histories erased and rewritten with the same lies. We have shared a trauma that is barely acknowledged, let alone understood, in the West (something I felt keenly going through the British education system), and we have shared the joy of reaching an independence we should never have lost in the first place. To now see this independence attacked as brutally as it has been in Ukraine is devastating. It’s for Estonians to care about as much as any Ukrainian, and it’s for the world to care about as much as any Estonian. While I have occasionally questioned my place in this project, I think my lack of immediate connection to Ukraine, combined with Daria’s very close connection, can perhaps help reframe the way we think about care and what is ‘for us’ to care and not care about.

If I understand correctly, your project is about weaving a tapestry of aural testimonies from Ukraine. What kind of stories were you looking for and what were the demographics you were concentrating on?

Daria: We’re not looking for stories — rather, we want to create a safe space where people can bring and share their own. We welcome participants of all ages and backgrounds. Their stories may differ, but this is exactly what’s needed.

The idea is to record / create modern Ukrainian folklore, the body of expressive culture. Being Ukrainian is something that many people experience not only within Ukraine, but across the world. You might live abroad, or have a Ukrainian great-grandmother, and feel a wish to reconnect with your heritage. Modern Ukrainian folklore is being written by Ukrainians everywhere, and their perspectives should be collected.

Why a tapestry? For us it is a mystical, fairytale-like form — one that fits naturally with the process of remembering and storytelling. Threads are stronger, when they’re woven together. Embroidering, it’s like telling your story piece by piece, word after word, stitch after stitch. It’s a tactile form of narration — intimate, yet communal. People can feel included while also having their own space for their story, creating a work made by many.

It’s a textile conversation in Ukrainian.

Helena: With consent, we will also record these stories as audio. This parallel tapestry of sound is, in part, our response to the plundering of Ukrainian art by Russian forces. One of the central aims of this whole project was to create something that cannot be destroyed or taken; something rooted in, and generative of, knowledge, memory, and connection. We hope this will be achieved on an experiential level via the workshops and physical creation of the tapestry, but we also wanted to explore this idea artistically, digitalising our tapestry onto a website to which Ukrainians from around the world can contribute beyond the project’s completion. The creation of an ‘aural tapestry’ is intended to further safeguard the permanence of our work, translating the stories and testimonies people have shared into the security of another medium, which, in this case, is further shielded by its immateriality. We hope to present this part of the tapestry in full towards the end of our project and will also incorporate it onto the website.

You used the world “folklore.” Are you inspired by Ukraine’s folk song tradition in any way?

We’ve been using the word ‘folklore’ as a way to bring together and find sense in the diverse stories we hope to collect, rather than in an attempt to draw on any particular style or practice. Similarly, the aural elements of this project could, in many ways, be seen as a sort of Ukrainian folk music, literally composed by and from the ‘folk’ of Ukraine, without necessarily referring back to any particular tradition or sound.

As a composer, how do you approach spoken words based works?

As a composer, how do you approach spoken words based works?

Helena: As I kind of mentioned, a lot of my work is rooted in the idea of there being an ‘unsound’; that any given articulation is already loaded with a sort of ‘unarticulation’ that exists both within and beyond the one we’re immediately presented with. From this perspective, I’m interested to see how ‘untold-ness’ manifests in and around the stories we collect and ultimately create from/with – what compositional possibilities are housed in the negative space of narrative?

How would you say the role of the artist changes in times of war?

Daria: Nowadays, the word artist has become a broad term, which is good. We have the freedom — and the responsibility — to engage more deeply, to help more. Artists today must share, stay grounded, and use their knowledge and empathy to support others.

In times of war, the artist becomes a mirror of society and its transformations, a shadow of society. The artist has a voice to tell stories, to tell the truth. In such moments, being socially responsible and deeply honest is not just a choice; it’s essential.

OCTOBER 22, 2025 – Bila Tserkva / in the army

Hi, I’m lebben, the founder of the lebben project and in the past the drum and bass project Ochitsuki. I’m a drummer and I just really love music, I collect vinyl, manga and everything I like. I’ve been making music since 2015, when I first discovered FL Studio and drums.

Has the full-scale invasion changed the way you think about music and sound in general and has your setup changed as a result?

The war changed my whole lifestyle, which was reflected in my work, and from the moment I joined the army – everything changed, because war became a more personal and less stereotypical concept for me. I try not to write about war in my tracks, because I don’t really like it because it’s everywhere, so I try to express my emotions with the help of images so as not to overexert the listener and myself. At least that’s how I like to write, because it most authentically conveys my vision of music in the context of Ukraine.

What can you tell us about the production process for цигарки vol. 2?

The production of this album took quite a long time, because after the previous split with Чортополох (Цигарки), I planned to immediately make a new release. The album was recorded half at OBLAZ Records, and half at home. I recorded it on cassette, and then digitized it, which is why the sound that I dreamed of before appeared, but could not reproduce due to the specifics of the sound of analog music media. Before I record a music release, some kind of reversible event always happens in life that changes my mental state, which is reflected in the music. And this release is no exception. Several tracks were taken and re-arranged from old releases from 2020, which, in my opinion, were perfect for this release. Plus, comparing to past releases, it seems to me that this release is a bit more than my usual EP, which I’m happy about

The album цигарки vol. 2 starts in an almost ambient mode, and the music for “два по ціні одного” is almost similarly ambient. And yet elsewhere the album flirts with jazz and even noise at times. How do you go about constructing the instrumental parts into a cohesive whole while mixing them with hip hop lyrics?

The album цигарки vol. 2 starts in an almost ambient mode, and the music for “два по ціні одного” is almost similarly ambient. And yet elsewhere the album flirts with jazz and even noise at times. How do you go about constructing the instrumental parts into a cohesive whole while mixing them with hip hop lyrics?

It comes more from my musical preferences and mood. I just make some instrumental, and then I write lyrics for it because it seems to me that the synergy with the beat is much better this way. It’s no longer about music, but about what mental state I have at the time of writing the track. For example, the track “костянтинівка” was written based on the period of my military service in this place and is more associated with a touch of sadness and a feeling of complete hopelessness.

I had the idea to create a musical score around the artwork. I had an album called найкращі друзі, and this artwork was created by a friend, inspired by my music. Music is very variable and in my opinion does not need specific genre frameworks except for formally defining the foundation of the song so that listeners can at least associate the music with something.

Is there a music community in Bila Tserkva that you feel part of?

I spent some time studying the music scene of Bila Tserkva, but, to be honest, I could not find people who would share my vision of music. The most interesting thing is that the city produces really talented musicians such as session drummer Mykhailo Galinin – but really interesting bands can be counted on the fingers of one hand. There used to be a pretty active underground rap scene here, but now it has mostly disappeared due to the full-scale invasion and lack of promise of the rap that was made in Bila Tserkva from 2015-2018. Nevertheless, I think there is a lot of potential here. Maybe I just haven’t been that deeply interested in the artists from my city. Considering that famous Ukrainian artists rarely come to Bila Tserkva, the local scene actually has a real chance to develop.

How would you describe the experimental and lo-fi hip hop scene in Ukraine and what would you say are its most interesting developments?

In my opinion, the lo-fi hip-hop scene in Ukraine is difficult to characterize due to the not so rich number of these artists. Plus, quite a few people mean by the word lo-fi any stream with lo-fi beats, which was previously popular, which is why the meaning of the definition of this genre is lost. Lo-fi is more likely not about the quality of the recording, but about emotions.

Are there any Ukrainian albums from the past four years that have captured current events in a meaningful way for you?

I like the mood of the Lasta release – Sunflower, which reflects the stream of consciousness and in general my mental state and the feeling of being in society. Of the latest releases that I listened to, I would note ЧОРТОПОЛОХ – глум, Увага – Сум’яття, івл івл – я непотрібен мені, almost any Zipcult album.

Do you ever suffer from burnout and how do you deal with it?

Do you ever suffer from burnout and how do you deal with it?

Burnout as such occurs for me after the album is released, so I usually take a break to not listen to any music, meditate to the sounds of nature in a local park. Despite the fact that music for me is more of a hobby and a way to sublimate emotions – in some places it is the same job, though without a salary and sometimes when thinking about a track – with brainstorming. With my approach “music according to mood” the option of rest and distancing is ideal.

What does it mean for you to be Ukrainian?

For me being Ukrainian means having a deep understanding of the historical, cultural context. it is about appreciating the community and the ability to unite even in difficult times. at least this is what reminds me of who we are.

Which book / film / album / song / traditional dish / podcast / blog / artwork / building / meme best captures Ukraine for you?

In my opinion, the best film that reflects Ukraine is Parajanov’s film Тіні забутих предків. It is difficult to single out something from music, because in my opinion all underground artists who write music in Ukrainian or in general on the territory of Ukraine are great guys.

OCTOBER 23, 2025 – In the army

Hi! My name is Andrii Dmytrenko – a frontman of indie band called adm:t. Before the full-scale invasion we played on the biggest music festivals in Ukraine: Zaxidfest, Respublica Fest, Koktebel Jazz Fest and dreamed about performance at Atlas Weekend. The irony is that we still haven’t done a single full-fledged solo performance yet. So I’ll keep these objectives after being demobilised someday.

Has the full-scale invasion changed the way you think about music and sound in general and has your setup and lyrics changed as a result?

To be honest, the war changed everything. If you`ll compare my old and new songs, the lyrics have become less carefree, almost every song now features war, and the music has become heavier and more rhythmic.

First of all, I have much less time for music now, and sometimes there is none at all. This, in turn, changed my approach for writing and releasing my songs. I no longer write them just in the “Demo” folder on my PC and try to finish every idea. I appreciate every second I have for creativity and every opportunity to work a little in the studio. Every time I’m in the studio, I can simultaneously record guitar and vocal parts for three or even more upcoming songs. Then all the recording I send to my teammate Taras Pidkuimukha – who makes brilliant mixing and sound for all my songs since 2019. Such online format made me more productive musician (in terms of the number of releases) during my military service than before. From other hand, as a band – we hadn’t have any rehearsals as well as live performance with Dmytryk, Kostyk and Sashko since November 2021.

How would you describe the indie folk scene in Ukraine and the music community in Kyiv?

How would you describe the indie folk scene in Ukraine and the music community in Kyiv?

I guess I’m not part of the music community. Especially now. And in general, I’ve rethought my sound and style, because I don’t use ethnic instruments classically in my songs, but rather ask Dmytryk to play parts on woodwinds that are more typical for guitar.

To my knowledge, the last couple of track you released are collaborations with Lisnyi, На Її Основі and Tember Blanche. How important are collaborations to you and how do these come about?

I planned my next EP as an album of collaborations with those artists who are close to me in spirit and whom I like to listen. Some of the songs have already been released: “Ах, життя моє дороге” with James Hot, “Метаморфосінь” with Tember Blanche (lyrics by Maksym “Dali” Kryvtsov), “Течія” with Terry Phao. I also hope to release the song “Швидкоплин” with musician and brother-in-arm Remez by the end of the year.

Collaboration with Lisnyi on the project “На її основі” is, if I may say so, a release that was not planned in advance. I am very proud of participating in this project and perhaps, after all, it will be able to include the song “Лід у воді” to my upcoming EP.

Ukrainian music seems to be thriving in spite of the war, but how do you see the scene evolving with many artists having now relocated and many being mobilised?

I think that those artists who are currently serving in the Ukrainian defense forces have something to tell – that’s why it’s important if each of them would find an opportunity to write and release new songs.

And I personally don’t accept and don’t follow those artists who left Ukraine after the full-scale invasion.

I understand you are currently serving. How would you describe the musical preferences of servicemen? Considering this is a very diverse group of people, have you noticed any dominant genres—say, metal or hip-hop—and do people exchange playlists?

It’s very difficult to generalize the preferences of all military personnel, but if I had to choose one genre, I would say it’s post-punk.

Has the constant stream of quick dopamine-releasing content from TikTok or Instagram replaced music as a source of instant gratification and comfort within the military?

Has the constant stream of quick dopamine-releasing content from TikTok or Instagram replaced music as a source of instant gratification and comfort within the military?

I still don’t use Tik-Tok. It’s a bit wild, I guess, isn’t it?

Are there particular songs or genres used to honour fallen comrades, and does music help in the process of healing?

Two of my songs are based on lyrics by Maksym “Dali” Kryvtsov: “Завтра?” and “Метаморфосінь“. We agreed on their publication while he was alive, but he was killed during combat actions in Kharkiv region last year.

My songs “Флешбеки“, “Течія” and the upcoming song “Швидкоплин” are dedicated to killed and missing brother-in-arms from the 207th separate battalion of the territorial defense forces. It is important to remember everyone as well as to build up a culture of memory.

What does it mean to be Ukrainian for you?

What does it mean to be Ukrainian for you?

To be territorially in Ukraine. To be active and conscious. To be a part of Ukrainian defence forces or to help them.

Can you think about the future and, if so, what does it hold for you?

Victory of Ukraine. It is different for everyone. But it is equally desirable for everyone. It won’t be tomorrow.

Which book / film / album / song / traditional dish / podcast / blog / artwork / building / meme best captures Ukraine for you?

My choice would be the next:

- Book: Artem Chekh – Гра в перевдягання (Dress Up Game)

- Film: Lesya Bakalets – Вода буде завтра (Water Will Be Tomorrow)

- Album: Remez – Кілометри (kilometry)

- Song: Renie Cares – “Дамоклів меч” (Damokliv mech – Sword of Damocles)

- Traditional dish: Деруни (Deruny)

- Best memes: Mysha v blindazh

OCTOBER 24, 2025 – In the army

I’m Remez, my name is Oleksandr.

Since I was 15, I played in rockabilly bands, also played and wrote songs in American roots way (old jazz, blues, yearly soul). My band RvB was active both in Ukraine and abroad. With the beginning of the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine, over time I began to release songs solo, as Remez.

What can you tell us about the Ukrainian Cultural Forces and the way they operate?

This is an organization that covers many different cultural needs at the same time. Both in the army and outside it. These include cultural events for the military, near the contact line, and social projects aimed at drawing attention to military needs, as well as cultural and diplomatic delegations around the world.

Does the role of the artist change in wartime and what role can music play in the war effort?

Of course it is changing! First of all, we have a very unusual situation, Ukraine has been under the influence of Russian propaganda for over 200 years and during this time, about 100 times the excesses of the ban on the Ukrainian language and culture were recorded. This also included shootings, torture and torture of artists and cultural figures of the country.

Because of this, now the job of any artist is to return us all to our culture, and this is a task with an asterisk! We also all know how art heals the soul, tunes it in, so we put a lot of effort into this direction.

Granted that people in the military come from very different backgrounds, how would you describe the musical preferences of servicemen and women? Have you noticed any dominant genres—say, metal or hip-hop—and do people exchange playlists?

In fact, there are as many genres as there are people. But since fighters often post on the Internet, it’s rap and post-punk, but no one has canceled AC/DC and Johnny Cash.

Has the constant stream of quick dopamine-releasing content from TikTok or Instagram replaced music as a source of instant gratification and comfort within the military?

This effect is certainly present! But when people do something like drive a car or cook food or chop wood, they listen to music.

When I interviewed Sasha Boole in Lviv back in May, he told me that one of the things he learned while serving is to write more direct, stripped down songs without worrying too much about production values, or making tracks too “ornate.” Is this something you agree with and how have you managed to keep your creativity going?

Sasha Boole is a great artist! I understand him well! Personally, I don’t have a specific approach to creating songs, sometimes direct language is the best solution, and sometimes I want to create an atmosphere with words and leave variability, as well as develop my poetics and storytelling.

But as for the recordings, I want to convey the emotion as purely as possible and I believe that lo-fi will be the most honest here, especially since the conditions in which I record and mix them cannot be made any better, and there is no time or money for that.

What makes me continue to create? For me, this is life, I can’t keep it to myself, and no matter how hard it is to realize it, without it there is no meaning to existence for me.

What can you tell us about the production process for your album Kilometres and what kind of feedback did you get from people in your unit?

I hope it’s too early to talk about feedback, because at the time of our interview, only a day had passed. But some people wrote to me that this is very sincere music and thanked me. Unfortunately, some music communities are ignoring the appearance of this album, which is a shame.

There are 2 different things here, it’s writing songs and recording them. The songs were written from 2024 to 25. I recorded it all in 2025, all by myself (except for the drums and piano in the flood song, which Lucas Byrd played) and the last song, where my wife sings. I recorded it in the car, then in the barn early in the morning before leaving for work, and something at home on vacation.

On a general note, are there any particular tracks that have become widespread among soldiers, or used in memes—and if so, what made them popular?

I think more about authenticity and less about popularity or memes. So I don’t know what to say.

Does music in the army reinforce stereotypes of masculinity, or amplify ideas of nationalism and identity as some claim?

Does music in the army reinforce stereotypes of masculinity, or amplify ideas of nationalism and identity as some claim?

Everything you say is true! But it also promotes reflection and encourages acceptance of reality and paints a different angle of perception.

Are there particular songs or genres used to honour fallen comrades, and does music help in the healing process?

Yes! In certain units there are certain traditions with burial. There is music for recovery, but I don’t work in those genres. I’m more of a storyteller and story collector.

What does it mean to you to be Ukrainian?

Haha! I don’t know how not to be Ukrainian. Despite the fact that I read books and watched films about life in other countries. But a lot of things come to us from birth, subconsciously. I must admit that since 2022 I have been discovering the country, people and culture in a completely new way, it is a very strange and pleasant feeling.

OCTOBER 25, 2025 – HELSINKI

photo by Renata Kazhan

Hi, and thank you for having me — it’s a pleasure to be featured in A Closer Listen.

My name is Yevgen Chebotarenko. I am a musician and audio technology specialist. In my teens, I started playing my dad’s guitar and messing around with different audio software, mostly writing down ideas and playing with sounds on my computer. Later, in 2007, I started a band in Odesa called My Personal Murderer. Back then, the band was quite a typical mockery of the Western rock music canon, which was often the case for Ukrainian bands of that time, though its genre changed quite drastically later on and the music became more abstract, so to speak.

My interest in audio technology evolved into a full-time profession, which deepened my knowledge of and appreciation for sound. These days, along with working for a company called Neural DSP, I am mostly focusing on electroacoustic music composition, which I studied a bit while in Finland.

I don’t know when you moved to Helsinki, but has the full-scale invasion changed the way you think about music and sound in general?

I moved to Helsinki in 2019. I don’t think I know the answer to your question yet. When the Russians invaded Ukraine in 2022, music was the last thing I wanted to think about. Only after some time did I start returning to it, slowly.

What is your production process and your home studio setup?

My process is relatively standard — I usually work in three stages: recording, mixing, and assembling the final piece.

For recording, I improvise and record the instruments I have, ask friends to play, or walk around with a field recorder capturing sounds I find interesting. After collecting sounds, I mix them by manipulating their pitch, spatial characteristics, applying filters, and so on, thus producing various so-called textures. I never know what I want to get in the end, and that’s the most exciting part of music-making for me.

To simplify the mixing process, I use computer software — mostly Ableton Live and the JUCE framework for the C++ programming language, which gives me the freedom to tweak things to my liking in the smallest detail — as well as the Elektron Octatrack hardware sampler, my all-time favorite piece of musical gear.

Once the “textures” are ready, I start improvising with them again, adding special effects and more traditional instruments or voice until I get a piece of music that feels right.

My home studio consists of a 14-channel mixing desk, a couple of microphones, a guitar, an analog synthesizer, a hardware sampler, and a bunch of guitar processors and special-effects units.

How did your collaboration with Samuel Van Dijk on Ear to Ear come about and what can you tell us about the way you prepare for a live performance?

We met at work. He shared his music, and I really liked it, so at some point I invited him over to listen and play some music together. The improvisation session we had went pretty well, so we decided to make it a tradition. Each time, Samuel brought some new and interesting piece of gear to play with, and we improvised for three to four hours, recording everything. There must be tens of hours of Ear to Ear recordings on his PC. Every such improvisation felt like a conversation — it was always exciting to hear what kind of sound would come next.

In the liner notes to Birth of a Song, you state that the album started as random moments of sound. How important is improvisation for you and how did the vocals come into play? Also, the sound of the album feels organic, did you use any processed field recordings?

Improvisation is fundamental. The only thing I usually plan before the recording process is which configuration of instruments and musical gear I’m going to use.

As for the vocals — it just felt right at the moment.

Regarding the organic sound, on Birth of a Song I used only two field recordings I am aware of: one of a bike parking lot next to the power plant not far from my place here in Helsinki, and another from a walk in the snowy forest. I also really love swamps — they sound amazing and mysterious — so I have a couple of pedals that helped me create that “swampy” feel: Moog’s MF-104M delay and MF Chorus.

I am intrigued by the cover artwork. What can you tell us about it?

I wanted something sexy, so I asked my girlfriend to take a photo of my legs.

Are there any albums from Ukrainian artists that have managed to capture current events for you in a meaningful way?

I enjoyed listening to the Shadow Play album by the Ukrainian black metal band Drudkh, released a couple of months ago. I think it fits the times pretty well.

photo by Renata Kazhan

How would you describe the electronic and experimental scene in Ukraine and what would you say are its most interesting developments?

I’m lucky to have talented friends, so I don’t have to look far to find good electronic music.

Trinidad Shevron makes haunting and visceral techno — I really enjoy the combination of heavy machinery and wailing soundscapes in his music; Promised Consort is my go-to track from him.

super inter creates very intimate and detailed music that can also be quite emotional — really well-balanced stuff. I especially enjoy her From the East release.

Renata Kazhan combines drone and pop music, and it works really, really well — very dreamy, and she’s also a great singer. I steal some ideas from her from time to time. Check out her song “Swift Sword.”

Just imagine how many more talented people from Ukraine are out there. It seems to me that, despite the existential threat that Russia brings to the people of Ukraine, the music scene is thriving.

Which book / film / album / song / traditional dish / podcast / blog / artwork / building / meme best captures Ukraine for you?

- The song would be “Любов” (Love) by Воплі Відоплясова (Vopli Vidopliasova).

- The book — Вірші з Бійниці (Poems from the Loophole), frontline poetry by the late Ukrainian soldier Maksym Kryvtsov.

- As for the blog, I really enjoy watching the Хащі (@hush.chi) channel on YouTube — a couple of guys wandering around Ukraine in search of abandoned places and good stories.

- I spent my best years in Kyiv living next to St. Nicholas Cathedral — the one damaged some time ago by the Russians — that would be the building.

- And finally, the dish: definitely varenyky with salty cottage cheese, egg yolk, and smetana. Celestial food.

OCTOBER 27, 2025 – Wrocław, POLAND

I’m a self taught music artist and sound designer from Kharkiv, UA. I’ve started making music at school as many teenagers do playing in bands on drums and/or keys/synths+live FX and learning to produce in my free time. Then served in 2014-2015 in Donbass when the war had just started. After demobilization, I rethought my life and started making music full time, working as a full time video game composer and sound designer. Also started to occasionally compose for theatre. Been doing it since.

Has the full-scale invasion changed the way you think about music and sound in general and how did it impact your motivation to make music?

The way I think of it (and not just music and sound, but life in general) has changed a lot earlier, in 2014.

The full scale invasion in 2022 made me stop doing any music at all, as I’ve started my volunteering activities to help the army and civilians from the first days of the invasion. I had neither the time nor any will to make music. To make music, I need time, distance and ability to reflect, and back then it was (and often still is) the wrong time.

Eventually, I started to compose for theatre and experiment with my own projects (just switch attention to something different). Volunteering remains my main priority, while music remains a friend, a helping hand, a safe harbour to stay for some time.

Could you describe your production process when it comes to creating soundtracks for the theatre, and at what point do you become part of the creative process?

Theatre gives lots of creative freedom for sonic experiments, and as a composer you also need to provide much space and time for the actors to improvise to. The same scene rarely lasts the exact same time twice, so you need to compose accordingly.

I love using my modular synthesizer and other hardware when it comes to theatre. Modular synth gives this focus, freedom, space, sometimes real weirdness needed, and I figured out that theatre+modular is a perfect match for me.

I also like to use field recordings, often processed via modular, especially granular processors. This provides unique sound textures and organic feeling. Processed field recordings are also a great tool to set up the tone and provoke associations you need for a scene.

Of course you also need software to record, process, mix and master it all.

You wrote about the emotional toll of working on She the War, a post documental play following the real life stories of 30 Ukrainian women of different age, character and experience caught by the horror of war. Was the choice of working mostly with analog gear a way of feeling closer to the characters?

Not quite. In fact, several themes improvised on a modular synthesizer were recorded long before the play came to life. These recordings just found their place in the play.

I had a hard time making music since my demobilization in 2015, but I realised that every single draft I recorded since 2015 was in fact my own processing of the war experience.

The play director and I were surprised to find how appropriate these aged pieces happened to be for the play’s context, and we used them almost unedited.

How did the production process change or evolve in the case of The Sea Will Remain?

Tech-wise, it was a development for me, because for the first time I was able to combine all tools I had at my disposal and make them work together. Modular synth, acoustic and electric instruments, vocals, field recordings, software – all worked in conjunction.

Emotionally, this was a hard experience. Since 2022, I’ve been trying not to dive into reflection and overthinking, because I need to stay functional and focused for my volunteering work. But this project had me take off my emotional “armour”, and it was like messing with the open wound.

On my next theatrical project, I’d like to perform live with a modular and some strange sound sources, which should be interesting.

How would you describe the music scene in Kharkiv and how would you say the artistic community in general has been holding up since the full-scale invasion and are formations like Some People keeping the cultural momentum alive?

How would you describe the music scene in Kharkiv and how would you say the artistic community in general has been holding up since the full-scale invasion and are formations like Some People keeping the cultural momentum alive?

I’m not in Kharkiv anymore. I moved to Wrocław even before the full scale invasion started to try and live somewhere else. Some can say I was lucky, others can blame me for not returning, but I keep a very close perspective.

Although it’s mostly my fellow military whom I help and talk to, not artists.

Anyway, cultural life in Kharkiv thrives, thanks to Some People, DK Art Area, Nafta theatre and more. New talents emerge, and they indeed have what to say with their art, unlike a lot of “art” nowadays which feels empty “art for the sake of art”.

Art in Kharkiv, Dnipro and other cities close to the front is different. It may not be so sophisticated, but it’s real, it’s sincere, and it has a lot to say.

Unfortunately, theatre workers are in trouble, there’s no state financing. So it’s always a personal initiative and personal funds to keep unorthodox culture running in the city. As it’s always been. Lots of respect for these people and their work.

How would you say your acoustic environment has changed since the full-scale invasion aside from the ubiquitous presence of air-raid sirens?

Again, for me it changed more in 2014. As of now, I’d rather let others who remain in Kharkiv speak about this experience.

My friend, a renowned film and game composer, records all shaheeds, rockets, bombs and AA guns and shares these recordings with me (and uses them in his work!). That’s his way to cope.

I have recordings of Grad missiles, rifles and mortars from my time at war, but also recordings of night forests, fields, night birds. There are very weird sounding birds in Luhansk region, I have never heard them anywhere else. They sound like some UFOs in dolby atmos, they’re circling around you and make these strange noises. So yeah, lots of interesting sound sources (dark humor).

But everyone agrees on this: there’s nothing more horrifying than an aircraft jet engine above you. It’s a combination of this evolutional thing of expecting danger from above, and also pure force of sound (sonic booms), infrasound affecting your subconscious, and conscious understanding what it may cause and how random its outcome can be. Fortunately, there are no russian aircraft above our cities anymore. But on frontlines – yes.

Does the role of an artist change in times of war?

I think yes and no. At the beginning, many artists felt obliged to express the horrors of war, to shout out loud to the whole world. Cultural diplomacy they call it. You feel you just must do something.

But not everyone actually can. Some artists are able to quickly process things and are able to quickly deliver their experience in a selected art form. Their art is like a live feed from the place. I respect this ability very much.

But I’m not that kind of artist, I process things very slowly. That’s why for me feeling that I MUST do it became a blocker. Only when I freed myself from this feeling of obligation, I became able to make music again. Music must help you and be your partner to live through events, I think.

And when you’re actually at war as a soldier – it’s quite hard to make music or to even think about it.

I tried, but the only thing I could do was just play with some software you have on your mobile device. Priorities become very different.

Are there any specific works by Ukrainian artists that have captured current events in a meaningful way for you?

Are there any specific works by Ukrainian artists that have captured current events in a meaningful way for you?

Yes, definitely. I’m sure there are a lot more than I’ve heard of. Also, wartime is a time to rediscover old artists in completely new ways. One example is an album by a songwriter, musician, actor, volunteer and warrior from Kharkiv Oleg Kadanov, a well known local artist and a deep personality. In 2022, he somehow managed to release an album Чи то так, чи то ні (something like “Is that so or is that not”) between his rides to frontlines to help military and civilians. These peaceful, minimalistic, very quiet songs made such a powerful counterpoint with horrors happening everywhere and all the madness of the world. This music just hugged you and told you “There’s still good. There’s love. There’s quiet. Easy. Just live”. And I understood this was exactly what I needed at that moment, just like a lot of Ukrainians everywhere in the world. This counterpoint was so timely and so powerful. I just embraced the feeling and surrendered to it for a moment.

Another example is my friend from Kharkiv, and artist and volunteer Katya Kharchenko, who has been drawing stylized flowers each day since the invasion started. One flower per day. She uses them to mark each day passed, sending them to her beloved at the frontlines. Her flowers evolved, and this consistency and evolution have become an important symbol of life and resistance for me personally. It’s not a very public art, but it’s a real art with the real story behind it, and this is what really counts, imo. Check it out on her Instagram. In fact, there is so much love expressed in Ukrainian art nowadays, it’s like everyone is trying to confess to a beloved one till they still have time.

Anton Slepakov and Andrii Sokolov from Dnipro with their project warнякання. This felt just like broadcasting all our collective 2022 experience via a series of beats, texts and visuals. Very powerful. Both of them have joined the military since.

A poet killed in action, Maksym Kryvtsov. He wrote a book of instant poetry Poems from a loophole while on the frontline.

A children’s writer Volodymyr Vakulenko, who was tortured and killed in Izyum. He wrote diaries of occupation and hid them in his parents’ yard before he was taken.

There are so many, and there are so many we’ve lost. But each single little story of help, support, kindness seems a true art in itself for me. Art of love, art of life that prevails. You just need to capture and remember it.

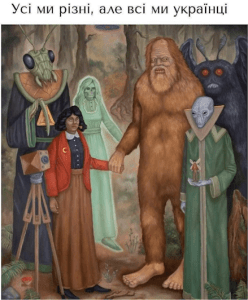

We are all different but we are all Ukrainian -meme

What does it mean for you to be Ukrainian?

To resist

To support

To give

To lose close ones

To want to live and love

To trust actions only

Which book / film / album / song / traditional dish / podcast / blog / artwork / building / meme best captures Ukraine for you?

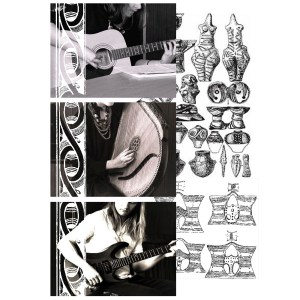

- Book: Hnat Khotkevych – Musical Instruments of the Ukrainian People

- Film: Oleg Sentsov – Real (2024)

- Artwork: Maria Prymachenko – A Menace of War

- Building: A bombed residential building in North Saltivka, Kharkiv

- Meme: всі ми різні, але всі ми українці (we’re all different but we’re all Ukrainians)

OCTOBER 29, 2025 – HELSINKI

I’m a musician and artist from Odesa. My musical journey began in 2015 with a band I formed with friends called Zukkor Zzov, where I was the singer and songwriter. It was a multi-genre project that started off rough, rockish, even punkish, and gradually evolved into ethereal, dark cabaret. The sound kept changing as I changed the lineup several times. Just when I was close to achieving the sound I was searching for, the band fell apart. That was in 2020. After that, I slowly began my solo project, which I’m still developing today.

Has the full-scale invasion changed the way you think about music and sound in general, and has it changed your playlist?

Radically. Now I can clearly see the connection between music and politics. The global position of an artist has become crucial to me. Suppression often speaks louder than manifestation.

I no longer believe it’s possible to separate art from the person who creates it. The “death of the author” doesn’t apply anymore. Before, I wasn’t particularly interested in who musicians were as individuals; that’s changed completely. The same goes for sound itself — it feels more radical, more intense. My playlist has changed accordingly: some artists have disappeared from it, but many new ones have come: Zelienople, Jan Jelinek, Tim Hecker, Scott Walker, OHYUNG, among others.

You work at the intersection of pop, ambient, drone, and electronic music. What is your setup, and how would you describe your sound?

My setup is minimal: a laptop, a soundcard, headphones, and a microphone. I work entirely in Ableton Live, using a mix of plugins, synths, and samples. I like the freedom of keeping everything inside the laptop. It’s a full studio and a space for exploration.

The process is about letting go of sound and then rediscovering it, collecting fragments, rearranging them, decoding the sense behind them.

My boyfriend once described my genre as “slow burn pop,” which I think fits quite well. My sound is intimate, atmospheric, and deeply textural. It values tone and transformation over structure or convention.

What can you tell us about the experimental music scene in Odesa and its evolution?

Unfortunately, there isn’t much to say about Odesa’s experimental scene at the moment. There are only a few spaces left for artists of this kind, and most musicians from Odesa have relocated to Kyiv or abroad. I would love to see it thrive again, but I have to admit that I witnessed its decline even before the full-scale war began.

How important is the visual element in your practice?

It’s important, though in a different way than before. It used to be central, I used to build everything around a visual image. My background in photography naturally influenced my musical approach.

But as I dove deeper into sound — learning, constructing, and actively listening — my relationship with visuality changed. It’s still significant, because when I compose, I perceive sound visually as well. But now the balance has shifted; the focus is more on sound itself.

Last April you released Hymera, a track composed entirely from samples and field recordings provided by friends, including essentialmiks, who is also from Odesa (now based in Germany). Considering you’re currently in Helsinki, is sonic connectivity important to you?

Of course. That was one of the main reasons I created this project. I wanted to explore active listening and see how many of those listeners already existed within my social circle. But the essential goal was to connect different people within a single piece of music — from the battlefield to safe places like Germany and Poland. I wanted to bring together sounds and worlds that would never meet otherwise.

What does it mean to be Ukrainian for you?

What does it mean to be Ukrainian for you?

Identity, to me, is something evolving. It’s not fixed or inherited; it shifts and must be built consciously.

Despite my background — the unrooted feeling, the “cosmopolitan” environment I grew up in, parents somewhat lost in that same atmosphere — I made my personal choice. It became clearer after 2014, and in 2022 it grew sharper and more defined. It’s probably the least I can do.

So I would say I’m growing my own identity. For me, it’s not about blood or history but about awareness and personal decisions.

Are there any Ukrainian releases from the past four years that have captured the war experience in a meaningful way for you?

СТАСІК — “Герої вмирають” (STASIK — “Heroes Die”). For me, it’s one of the strongest examples, painful and beautiful at the same time.

Yevgen Chebotarenko — Birth of a Song. It comes from a completely different universe than the first piece, but I think it captures this feeling of longing, sadness, and that anxious state you eventually learn to live with.

Which book / film / album / song / traditional dish / meme best captures Ukraine for you?

- Film: Babylon XX — Ukrainian poetic cinema.

- Album: Recordings 1987–1991, Vol. 1 by Valentina Goncharova.

- Song: “Велика ріка Хєнь-Юань” (The Great Hen-Yuan River) by Цукор Біла Смерть (Sugar White Death).

- Traditional dish: Borscht — 100 percent!!!

- Meme:

Захеканий мудило (лежачі долі). Там масла дохуя! [Panting jerk (lying on the ground). There’s a shitload of butter!]

Всі мудила. Де? [Other jerks. Where?]

Захеканий мудило. Там! (Помирає). [Panting jerk. There! (Dies.)]

OCTOBER 29, 2025 – CZECHIA

I’m Artem Sharko, and this is my solo noise project, named after my last name. I occasionally participate in various genre projects with my friends. I don’t really have a musical background. I’ve been playing instruments my whole life, starting in childhood.

Has the full-scale invasion changed the way you think about music and sound in general and has it changed your playlist?

Yes, absolutely. I began to take a deeper interest in noise and sound texture, it served as a meditation and distraction. This is where my first works and recordings came from. Overall, I’d say I was stuck for a long time, not really listening to anything, and then I rediscovered music. This project is a form of self-reflection, and noise is good at that.

What is your setup and your favourite piece of gear and what would you say is the defining trait of your sound?

Literally Ukrainian Field Notes. All the equipment is small devices and battery-powered synthesizers that fit in a bag for playing outdoors. The project has been going on for many years. I can go on a bike ride with friends or hike in the mountains and quietly jam away for the birds. My main and favorite instrument here is the Microgranny Monolith granular sampler from the Czech company Bastl Instruments. I started in Kherson when I was making tape loops and only had a Monotron Delay and Pocket Operator 32. They’re still used on my recordings. I also have a small Dude mixer, also from the Czechs, which I use in No-Input mode. Sometimes I use a re-flashed Zoom G1 Four bass multi-effector.

That’s where my portable basic setup ends. For recordings and performances, I also use an analog Behringer mixer and a distortion pedal with a piezo mic connected to the chain. And sometimes my Yamaha synthesizer also runs on batteries. But it’s almost never on the recordings.

Your first release is titled Rybníček – Stop of René Matoušek and other Liberec signatories of Charter 77 a real bus stop in the city of Liberec where you reside. It is inspired by Charter 77, the human rights manifesto and civic initiative in Czechoslovakia that began in January 1977. It was a document criticising the government for failing to uphold the human and civil rights it had previously agreed to in international pacts like the Helsinki Final Act and was motivated in part by the arrest of members of the rock band The Plastic People of the Universe. What can you tell us about the production process and the use of field recordings?

Your first release is titled Rybníček – Stop of René Matoušek and other Liberec signatories of Charter 77 a real bus stop in the city of Liberec where you reside. It is inspired by Charter 77, the human rights manifesto and civic initiative in Czechoslovakia that began in January 1977. It was a document criticising the government for failing to uphold the human and civil rights it had previously agreed to in international pacts like the Helsinki Final Act and was motivated in part by the arrest of members of the rock band The Plastic People of the Universe. What can you tell us about the production process and the use of field recordings?

Well, at first, before the full-scale invasion, I just wanted to create a harsh noise project for fun. And I liked the fact that the stop name was so long. When they announce the stop, you can hear the announcer getting tired and trying to drag it out in one breath 🙂 And the Blackmetal logo, which is on the cover. Essentially, the question says everything about the charter. Of course, I immediately became interested in what kind of charter it was, and it reminded me of the story of Vasil Stus and the parallels with the Ukrainian Helsinki Group.

The idea was to mix samples as if I were streaming my thoughts from my head. They have nothing to do with Stus or the first president of the Czech Republic; they’re just samples I found somewhere, perhaps related to the context of that time. Indiscriminately, Czech and Ukrainian fragments, and not only from films, cartoons, and TV shows in short, it’s all about emotions. That’s what noise is. I’d like to especially highlight the fourth track, recorded on a voice recorder in the forest on the equinox, where you can even hear the birds singing. This is essentially my first full recording, so it’s so important to me.

Exactly one year from now, I’ll be performing for the second time at axis fest, where I’ll be performing with Czech underground giants Markoman Electronics. Incidentally, they’ve greatly influenced my sound. Special shoutout to Marek from Bahratal, v0nt, and zimoles. Thank you so much for the invitation to Gregory and congratulations on the release of Hothouse.

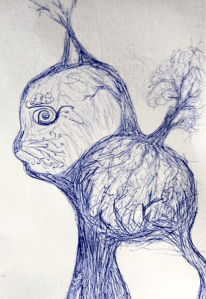

Your second release Koty (to the cat) is dedicated to the animals affected by war. It reflects your personal experience of losing a friend and your feelings for animals as victims of war. The album could be defined as folk noise, what can you tell us about the use of folk instruments and the looped snippets of singing and speech embedded within the overall noise texture and how do they relate to memory, in the sense of both collective and personal memory?

Your second release Koty (to the cat) is dedicated to the animals affected by war. It reflects your personal experience of losing a friend and your feelings for animals as victims of war. The album could be defined as folk noise, what can you tell us about the use of folk instruments and the looped snippets of singing and speech embedded within the overall noise texture and how do they relate to memory, in the sense of both collective and personal memory?

Yes. Releasing a track is an experience both personal and collective. I first tried recording on two tracks. On one, I played a full live performance, playing around with the main motifs, and on the second, I played some loopy sketches that had been sitting in my head for quite a while, using very short sections, and also tried polyrhythms. Returning to instruments, I unleashed the potential of the granular sampler, using the additional capabilities of the MIDI output. It’s hard to say where and how I get samples. It’s always different, and it’s what resonates with me. For example, I watch a film and I really like that sound. I’m a fan of the Dovzhenko Film Studio, as well as the Barandov Film Studio. This is where the interweaving of samples comes in. I like juggling them. I graduated from music school and was around string players for a long time. It’s an echo of my childhood. I like the sounds of radio and instrument tests. I really, really like the chaotic nature of philharmonic settings. By looping, I can control this chaos. Calling it folk noise is quite difficult, and I really hope it’s just that. Three collaborations and recordings with live instruments are planned for the future.

The first and last tracks, designated by capital letters, refer to my cat. It so happened that the viscous, bloody hand of war touched my heart in the form of my cat’s death.

Through looping samples throughout the record, I depicted a moment in life, the coming of war from without through the sound of drums and brass, a moment of forced migration, unfamiliar sounds (Czech hum, attention, test), peace, and, again, the echo of war, because being in the Czech Republic, you’re still not safe. I’m a migrant researcher who lived in the Czech Republic for many years, even before the full-scale war began. My parents couldn’t leave for a long time; they were occupied for a year, and then, with great difficulty, they moved to me in the Czech Republic, and a month later, Kherson was heroically liberated.

My cat was a stray ginger and often had territorial fights. He’d wander outside all day and come home in the evening to eat and sleep. He would often come home bruised, but was always happy to see me. After moving to the Czech Republic, he developed heart problems.

He died before my eyes. If not for the war, he would still be alive. I grieved this loss for a long time. I’m quite sensitive, and this loss was comparable to the explosion of the Kakhovka Reservoir dam. There were so many casualties back then. I remember conversations with people in Kherson before the water had risen, but everyone understood it would be very difficult. (I also wanted to convey this in this release.) In Kherson, there was an outbreak of diseases associated with toxic substances found in the water. All the music in this release is about the time of the flooding of southern Ukraine and the sacrifice of animals that still exist today.

The impact on Askania-Nova, a biosphere reserve in the Kherson region, is especially worth noting. The scorched Serebryansky Forest (a needle of which found its way into my monotron and is still there). The devastation of the Dzharylhach national nature park, and so on.

Everyone will hear something unique in this release. There’s a reflection on the flood, and a memory that rushes past like a ringing sound, never fading. With each beat, the sound grows louder and louder. The noise is memory, it’s pain, and the ringing in the ears is all “Memory” (the last track). Every soul is not forgotten, and everything will remain as heaviness in my chest.

The cat was my friend and even a “work colleague”; I wrote my dissertation with him when I was in Kherson during COVID. He helped me experience a ton of emotions in my life. When I picked him up as a kitten, he had a great sense of rhythm, which is why he was named after the jazz drummer Buddy Richie. A little ginger piece of happiness in my heart, which is now forever gone.

Like the first release, this one was again created with a touch of humour. The funny cat and the name of the cat are a nod to Kharkiv punks and their songs about a cat, about a father, and about themselves. Despite the pain, you should always treat everything with warmth and joy. I only remember the good.

You are originally from Kherson, what can you tell us about the music scene in your hometown prior to the full-scale invasion?

You are originally from Kherson, what can you tell us about the music scene in your hometown prior to the full-scale invasion?

The Kherson scene is very interesting, spanning a variety of styles. Many have migrated to other cities. I’d like to highlight Andrey separately. An old childhood friend of mine whom I’ve known my whole life. My godfather in music, who led me by the hand into an entire era. He was already on Ukrainian Field Notes when he presented his project Merti Dereva. He is a master of the Ukrainian heavy scene. I like all of his projects without exception.

Check out Signals Feed the Void specifically. The guys from South Death Circle and the Kherson breakcore scene are also good. Suck Puck Records is worth mentioning. Although it’s closer to Odessa, there are a lot of Kherson artists on their compilations. There are actually a lot of musicians, and the punk scene is also good.

Are there any Ukrainian releases from the past four years that have captured the war experience in a meaningful way for you?

Are there any Ukrainian releases from the past four years that have captured the war experience in a meaningful way for you?

Yes, there are many significant ones, unfortunately, related to the loss of project participants who gave their lives in the war. I haven’t seen anyone who actually shared their military experience. It seems like lately I’ve only heard about war crimes or reflections on the war. Again, I’m reminded of the work of my friends Gvalt. Also, the projects of Andrey Waidelotte.