Artwork by Mariia Prymachenko

It’s now been four years since the full-scale invasion with little to feel optimistic about.

This month we talk to kyïvite about radio broadcasts and archival recordings while Polygrim describes his production processes as playing with Lego on steroids and Konstantin Kost displays his penchant for VHS aesthetics in Odesa, whereas Doctor Bugg admits to a strong attraction to scientific thinking combined with a parallel pull toward agnosticism.

At the same time, Axxi Oma finds new inspiration in Amantea, Italy, G.Inc discuss their production process while living in different cities, and Pencil Legs muses about liminal spaces and finding inspiration in Beckett.

Lisa Stuzhuk and Vitalii Symonenko

For our monthly podcast for Resonance FM we talk to Symonenko and Lisa Stuzhuk from СМИК about fusing traditional melodies and electronic beats.

Tracklist:

- Володар [Volodar] – “Не розвивайсь дуб зеленой” [Don’t Grow Green Oak Tree]

- maxandruh feat. Symonenko – “Кіт і Михайло” [Kit and Mikhail]

- Parking Spot & Oriole Nest – “Сербен” [Serben]

- Symonenko and DvaTry – “ZACHEPYKHA”

- DvaTry – “Dovbeshka”

- Symonenko – “Весілля у Гуцулів” [Hutsul Wedding]

- Symonenko and DvaTry – “Tanets Svativ”

New Releases include albums by Collage Y, Dub User, Hillmer, Khrystyna Kirik, Chloe Landau, Delirium, Amphibian Man, Yehor Tymchenko, Rushnichok, hjumən, ken=en, Timur Basha, ZzuppamanN, and 58918012.

@velocitypress

In the Viewing Room we have “Foie” by Ombrée traken from the album Calvaire released by I Shall Sing Until My Land Is Free with all proceeds going to Ukraine. Video by Natalie Ancona and Guillaume S. Ombrée.

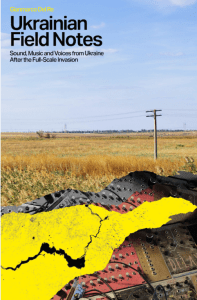

On a personal note, Ukrainian Field Notes is now also a new book currently on pre-order at Velocity Press. Drawing from four years of interviews with over 300 artists, deejays, sound artists and cultural practitioners, UFN explores how sound and listening reveal the human experience of war. It examines how the aural environment has been transformed by explosions, alarms, and their sonic by-products, and how these new acoustic realities are being reinterpreted or erased from the language of electronic music.

JANUARY 30, 2025 – KYIV

My name is Kvitoslava. I am a radio host from Podil in Kyïv. My background is in electronic music, but the kyïvite project grew out of listening rather than composing. For many years I’ve been listening to archives and old recordings, trying to comprehend how music survives when it’s no longer performed live. I’ve worked with sound in different forms before, but kyïvite is not about creating, it is about transmitting the signals of the past to the future.

How has the ongoing war affected your creative process, both emotionally and in practical terms?

The war made listening feel urgent. Our ears are now catching every single frequency – from the lowest to the highest ones. Emotionally, it sharpened the sense that culture can disappear quietly: not only through destruction, but through forgetting. Practically, it pushed our project towards formats that are light, minimal, and imperishable. Radio felt right because it doesn’t demand much performance. It works even when everything else stops, which is now, unfortunately, extremely relevant to the situation in Ukraine, and in Kyïv especially.

Can you tell us about the production process for the broadcast on 09/01/26? I understand you sourced some of the sound from Wikimedia Commons — do you see yourself working with archives more in the future?

The first broadcast was created quickly, within just a few days. As a first step, the list of archival recordings available in public domain was made, as far as in our broadcast we put the author’s rights first. We worked with archival recordings that can be found in the public domain on Wikimedia Commons, treating them carefully, not just as samples, but as voices.

In the future, we would like to work more deeply with archives and also with private collectors and researchers. Archives are not only about music, sometimes you can hear conversations and voices from the past there, which is truly special and extremely valuable too.

How important is it to you to bring Ukraine’s artistic heritage and folk traditions to a wider, international audience?

It’s important, but not in an educational or representational way. We believe that listening creates its own understanding. The task of our project is not to explain music, but to let it pass through the air once again. As a palimpsest, to keep this tradition alive, whatever happens in this chaotic and unjust world.

Since the full-scale invasion, a lot of electronic producers have been working with folk themes. How do you feel about mixing the old with the new?

For us, it’s not even about mixing. Old and new already coexist – archives become contemporary the moment we listen to them again. What matters is care: not turning tradition into decoration. It should be certainly approached with respect and deep understanding of influences, historical contexts and transformations. Folk is a fragile material that helps us find guidance for the future development of Ukrainian music and communicate it to the international audiences.

Ukraine has an incredibly rich musical heritage. What have you been discovering while doing your research

What struck most is how much of it exists without names. So many songs survive without authors, dates, or fixed versions. That anonymity and variety feels very unusual to us. It is very inspiring too, because it puts music first, leaving no room for over-personalisation. We are also discovering how regional and fragile these traditions are, and how easily they could vanish. But still we can clearly see and experience them till nowadays.

How far ahead have you planned future releases, and what can we expect from you over the next few months?

We work broadcast by broadcast. There are a few upcoming transmissions already imagined – each focused on a different period or tradition, but we still prefer to leave space for chance discoveries. It’s possible that we may run out of old music available in the public domain. So we are very much open to making collaborations with Ukrainian music archives. However, apart from the format of a remixed broadcast, we already have in mind other options of discovering old Ukrainian music.

What does being Ukrainian mean to you personally?

What does being Ukrainian mean to you personally?

Being Ukrainian means to be surrounded by music and sounds. From my early childhood, even though I am not from a musical family, music was all around. Seems like the motifs of Ukrainian melodies are somewhat “sewn” into our DNA, and each tradition is represented in sound, in its own way. Being Ukrainian also means carrying memories that aren’t always visible. It’s a form of responsibility, especially in the times of struggles for independence and freedom.

Is there a cultural reference that captures Ukraine for you?

Ukrainian culture is first of all about variegation. The variety of melodies is striking, as well as the timbres of voices, and also regional peculiarities and dialects. Listen to Ukrainian children’s choirs, to solo singers, or any kind of instrumental music, listen to music from Polissya, Kharkiv region, Lemko region – this all can put you into different moods and spaces, bring you joy or sadness, this all can comfort or enamor your hearts. They say, we all are different but we are all Ukrainians. It’s felt most clearly in old recordings, created before the era of globalisation. Sometimes the textures there are quiet, sometimes thundering loud, sometimes clean, and sometimes damaged. The manner of singing and pronunciation is never the same too. They carry voices that were never meant to last, yet they did. That’s where we recognise Ukraine.

FEBRUARY 4, 2026 – KYIV

photo by Valeriy Arhunov

My name is Volodymyr, I am from a little village near Kyiv, location-wise. Time-wise, I am from the era of expensive dial-up internet when information was non-existent, so you had to acquire it by self-teaching.

I spent my early teen years living inside my headphones, I didn’t have any gear at all apart from a PC. I had this stereo with a radio I’d listen to religiously. One night a trance song came on, I didn’t even know what genre it was. I was blown away with the melody and this massive wall of sound. Some kind of revelation, really. As this was a DJ mix, there came another track, then another one, then I learned it was a late-night weekly show on one of the FM radio stations.

One day after school, with pocket money I spared, I impulse-bought a CD with this daft music software I had no clue about. I started clicking around and something about that changed me forever – an idea that you can make a new piece never heard before. It felt like playing with Lego on steroids, but instead of plastic bricks, I was building with emotions.

Eventually a few of my tracks hit that radio show I started with, even met those DJs in person at a party, they shook my hand and said they knew who I was. That was an eye-watering moment.

Although there was some success in bigger worldwide shows, soon that carefree curiosity-driven enthusiasm started to fade. Aiming for the inclusion in the DJ playlists turned a joy into a source of constant immense loud anxiety. I was trying to run an exhausting race I didn’t want to – it’s just not for a quiet type who listens to shoegaze, dreampop, post-rock and more experimental electronica.

So in 2012 I decided to pull the plug and promised myself to do what I truly love. I purchased a copy of Logic Pro to emphasize the feeling of a blank canvas. After a few years of detox, one day a track called “Minimoon Voyager” naturally poured out of me, effortlessly. It was as if I saw the sky for the first time after being locked up in my head for years. That was the start of Polygrim.

Both your full length albums are built around strong self-imposed constraints—technical limits on Colorspacious, emotional and historical realities on Brimming. How do limitations shape your creativity, and do you feel you work better when something external forces your hand?

I believe limitations cure from overthinking. With Colorspacious I was fighting the urge to hoard new toys. I decided to stop buying gear and just squeeze the last drop from the available tools.

With Brimming, the limiting factor was relocating my family to a safer place with the beginning of the russian invasion. It meant I had to fit my studio in a backpack in a rush – just a laptop and headphones. Funny enough, since returning home, not much has changed.

Colorspacious was about making fully synthesized music feel organic, while Brimming brings in live instruments and human performances during a time of upheaval. How did your relationship to “organic” sound change between these two records?

Just before the invasion I was lucky to record live sessions. I find acoustic guitar the perfect glueing factor for synthesized elements. It just falls into the mix without much fighting.

Live drums are different. They are staple, but for me, they are hit or miss. I love the process of programming rhythms so much that handing them to a drummer feels like letting someone else build my lego.

Besides, the line is blurry, not sure you can count that as organic, but many of my synthetic sounds are just field recordings with layers and layers of processing.

Talking about the production process for Brimming, you stated that as the worst events unfolded, you felt compelled to write more cheerful music. Was that a conscious act of resistance, emotional survival, or did it happen instinctively?

I have always had a sweet tooth for cheesy and uplifting melodies, since I was a kid listening to Jean-Michel Jarre and ABBA and later trance music. There is a conflict – my adult brain wants to be serious, but my instinct is to write simple major tunes. Usually I quarantine those ideas, maybe out of fear to be misunderstood, or to feel too vulnerable. But that’s a good skill for my work as a game composer – it is actually hard to find good childish soundtracks. With Brimming, I purposefully let some of it through as I realized I might not have the luxury to wait for a ‘smart’ song, so I stopped filtering too much.

Honestly, the world was heavy enough already and adding with the soundtracks for the apocalypse to its

heaviness seemed counterintuitive. And besides, how often do you hear something non-depressing or

non-pretentiously-melancholic?

On Brimming, you revisited and reshaped earlier material rather than abandoning it completely. How do you decide when a piece of music still has a future, even if the context around it has radically changed?

A melody. Or at least a chord sequence. I always start from that. A good melody is stubborn. It refuses to die if the project falls apart. But a good melody is also fragile – use it with improper orchestration or pace and the project will fall apart. It sometimes takes three-four attempts to get it right enough. I often go through my collection of ideas looking for one melody or chord progression that still has a pulse after all these years of collecting dust. And I don’t worry too much about cohesion. Maybe due to the lack of that fine skill – I don’t need a song to match to belong together in a release.

Colorspacious feels like a carefully designed sonic ecosystem, while Brimming feels more reactive and lived-in. Do you see these albums as opposites, or as two chapters of the same artistic trajectory?

I hope to iterate on both and marry them in the future, both of these albums were a good learning experience. Since “Expect Subtle Miracles…” I dug deep into sound design. Before that the hummed melodic idea was the essence, everything else is just an optional decoration. Then my craving for interesting sounds dropped a shadow on just the melodic backbone of a song. The dream is the hybrid. I want a melody that gives you shivers, wrapped in a texture of a comfy dense wool blanket.

Collaboration plays a visible role on Brimming, especially given the circumstances around it. Did working with other people during wartime change how you think about authorship and ownership of your music?

That’s the thing I’d definitely like to practice more. Collaboration shows you new trajectories, but you have to loosen your grip.

On “Airframe,” I tried to add acoustic guitar as the main part along with acoustic drums. But the session player, despite being a very talented and prolific performer, didn’t match the blueprint in my head. It didn’t do justice to the melody, so I stripped it back and just kept the drums. Of course, all artists are credited and get paid.

I do dream of collaborative work, though my fear of rejection tells me not many artists would accept my invitation. I worry about the ownership because once before the war my track was stolen by russian rappers. It wasn’t ‘sampling’, it was looting.

Looking back now, what did making Brimming teach you about yourself as an artist that you couldn’t have learned while making Colorspacious?

It taught me that I’m still a hoarder. I struggle to kill the bloat because I get attached to the effort I put in, even if the result is clutter. I’m still learning to subtract and not to add, to learn to stop when a track works, not when it’s full. I hope some of these shortcomings will be tended in the next release. Until I think that about the next release – it’s a never-ending process. There is a reason why artists wait for years before they debut.

What does it mean to you to be Ukrainian?

It means finally standing on solid ground. For years, it felt like the world looked at us through a dirty filter – seeing only cliches, mostly negative, and it was sad to me.

Nowadays, despite many problems we have, being Ukrainian feels like having a spine of steel. It’s the soothing relief of knowing you are on the right side of the fence.

photo by Valeriy Arhunov

Four years into the full-scale invasion, how do you expect the situation to evolve, do you have any faith in the “peace negotiations”?

I can’t express how much I want this war to end. I want to finally know I will get up in the morning and not be crushed by a drone or a missile, go for a ride in the night, travel abroad again, meet my close ones who live there, plan the next vinyl release, live in peace. My gut says it will go on like this for years.

Which book / film / album / song / traditional dish / podcast / blog / artwork / building / meme best captures Ukraine for you?

It’s impossible to capture a whole country with one item. So these are the first ones that come to mind (sorry if I forgot something obvious).

Book: Ukraine from Above by Ukraїner / Film: U are the Universe / Podcast: BBC Ukrainecast / Song: Mykola Leontovych – “Shchedryk” (Carol of the Bells) / Food: Varenyky / Album: ONUKA by ONUKA / Blog: Ukraїner / Artwork: The works of Maria Prymachenko / Building: The Golden Gate of Kyiv / Not a meme guy

FEBRUARY 5, 2026 – ODESA

Hi, I’m Konstantin Kost, a techno and dub techno producer from Odesa, Ukraine.

My work focuses on deep, atmospheric and driving sound — music built around mood, tension and immersion.

Alongside producing and DJing, I also create visual content for my releases. I shoot and edit my own videos, often using analog and VHS aesthetics, because for me sound and image are inseparable. My goal is always to create a complete emotional experience, not just a track for the dancefloor.

Over the years, I’ve developed a sound rooted in hypnotic rhythms, deep textures and subtle intensity — music that speaks through atmosphere rather than obvious hooks.

How would you say the ongoing war has influenced your creative process, both emotionally and practically?

The war has affected me deeply, as it has every Ukrainian. Emotionally, it changes your perception of reality — your priorities become sharper, your mindset more focused.

For me, music became a form of stability. While many people escape through destructive habits, I chose to invest even more energy into my work. Creating music gives me structure and strength. It helps me stay disciplined and goal-oriented despite the uncertainty around us.

Practically, of course, the situation makes everything harder — fewer events, limited opportunities, constant stress. But at the same time, it has made my sound more intense, more honest, and more stripped down. There is less illusion now — only pure expression.

What can you tell us about the production process for the EP Bodies and how did your collaboration with Kevin Belton come about? Also, were you and Volodymyr from Vortex, the label releasing it, already familiar with each other’s work?

The Bodies EP on VORTEX is a cross-border collaboration between myself and Kelvin Belton. We’ve known each other for quite some time — music connected us naturally. What started as an experiment turned into an ongoing collaboration, and over time we built a strong creative partnership with several joint releases.

The EP focuses on tension, movement and physicality. We wanted to create tracks designed for dark rooms — hypnotic, driving, functional, but still atmospheric and immersive.

I’ve also known Volodymyr, the head of VORTEX, for many years — he is from Odesa as well. I’ve always respected his vision and consistency. Especially in these difficult times, maintaining an underground label and continuing to release quality techno requires real dedication. That commitment is something I truly admire.

How would you describe the techno music scene in Ukraine and specifically in Odesa and how do you see it evolving under present circumstances with many producers having left Ukraine and many more having joined the Armed Forces?

The Ukrainian techno scene is going through a very difficult period. Many artists have left the country, others joined the Armed Forces, and the overall social atmosphere naturally affects nightlife culture.

Kyiv still has activity — promoters are making serious efforts to keep events alive. But economically and socially it is much harder than before.

In Odesa, the situation is more fragile. The community has become smaller. Even when we organize events under our Overspeed collective, gathering 100 people can be a challenge. It requires a lot of energy and belief to keep things moving.

I believe the scene will rebuild and evolve after the war ends. Ukrainian rave culture has strong roots. But right now, survival — both personal and cultural — is the priority.

Has the demise of Port signalled the “end of an era” or is electronic music still very much alive and well in Odesa?

The closure of Port (DSK Port) definitely felt like the end of an era. It was an important space for the city and for electronic music culture.

But nothing is permanent. Scenes change, spaces close, new ones appear. Electronic music in Odesa is still alive — maybe smaller, maybe more underground, but still alive.

Rave culture doesn’t disappear. It adapts.

Odesa comes up as a major source of inspiration in your work. Are there specific sounds, rhythms, or moods from the city that you feel directly translate into your tracks, even subconsciously?

Odesa comes up as a major source of inspiration in your work. Are there specific sounds, rhythms, or moods from the city that you feel directly translate into your tracks, even subconsciously?

You need to be from Odesa to truly understand it. The city has a very specific energy — a mix of history, decay, poetry and raw honesty.

For me, the biggest inspiration is the sea. The sound of wind, the humidity in the air, the long empty horizons — they create a sense of depth and space that naturally translates into my music. Odesa has a strong, almost magnetic atmosphere. Here, writing music feels as natural as breathing.

Even subconsciously, that mood — melancholic but powerful — finds its way into my tracks.

What does “space” mean to you musically—distance, depth, silence, or something else entirely?

For me, space is not emptiness — it’s tension between sounds.

It’s depth, distance, and controlled silence. It’s the feeling that something exists beyond what you immediately hear. In techno, space allows rhythm to breathe and emotions to expand. Without space, there is no hypnosis.

You work with a lot of hardware. Do you approach your machines more as precise tools, or as unpredictable collaborators that sometimes push the music in directions you didn’t plan?

I see my machines as collaborators.

Of course, they are precise instruments, but hardware has character. Sometimes an unexpected modulation or imperfection creates something better than what I originally planned. Those moments of unpredictability often lead to the most honest results.

I control the direction — but I allow the machines to speak.

Since you’re also involved in video editing, how do you imagine the visual world of your music— do you see images while you’re composing, or does that come later?

When I compose, I often see images. My music is very cinematic in my mind.

I’m deeply inspired by VHS aesthetics — grain, distortion, analog imperfection. It feels human and nostalgic, like a memory that isn’t perfectly preserved. I like building small narratives around my tracks, imagining forgotten warehouses, empty industrial landscapes, late-night movements.

For me, sound and image are inseparable. Music creates the world — visuals simply reveal it.

Are there any releases from the past four years that have captured current events in a significant way for you?

Every release is significant to me. Especially when my music is pressed on vinyl and released through respected labels — that still feels meaningful in a digital era.

Vinyl represents permanence. In unstable times, creating something physical feels powerful.

What does it mean for you to be Ukrainian?

For me, being Ukrainian means resilience. It means continuing to create, work and move forward despite pressure. It’s strength without theatrics. It’s dignity.

How are you coping with the winter conditions?

Winter is always difficult — both physically and emotionally.

But discipline helps. Routine helps. Work helps. I stay focused on music and projects. Staying active mentally is the only way to stay strong.

Four years into the full-scale invasion, how do you expect the situation to evolve, do you have any faith in the “peace negotiations”?

Four years into the full-scale invasion, how do you expect the situation to evolve, do you have any faith in the “peace negotiations”?

After four years, you learn not to rely on political statements.

Real life is happening on the ground, not in speeches. I don’t put blind faith in negotiations — history has shown that words are often strategic, not sincere.

What I believe in is the resilience of people. The outcome will depend more on strength and endurance than on promises.

FEBRUARY 5, 2026 – KYIV

photo by Yurii Dyban (Xerxerash)

Doctor Bugg is a Ukrainian industrial hip-hop project built around text, tension, and live transformation. Language sits at the core of the project, but songs are not fixed forms here; they mutate on stage through noise guitar, distorted electronics, and free improvisation with saxophone. This is not protest music in a direct sense, and not folklore either. It deals with internal pressure, fractured identity, and the body reacting to sound. The live performance is closer to a ritual rather than a concert: structured, but never fully predictable.

My background comes mainly from instrumental and experimental music.

From 2017 to 2022, I played saxophone in Le Cru – a sax–bass duo focused on aggressive, punk-driven sound, irregular “mathematical” structures, and physical intensity. The form was minimal, but the energy was deliberately confrontational.

Around the same period, I was involved in Paranoise Cru – an improvisational project built around drums, bass, synthesizers, didgeridoo, and saxophone, with a strong performative dimension. The music was often accompanied by butoh performers, so sound, body, and space were treated as a single system rather than separate elements.

Another important chapter was Brainhack Musicbox, a project led by Stas Bobrytskyi, where modular synthesizers intersected with free jazz. In 2023, we toured the Netherlands with this project, which strongly shaped my understanding of live risk, extended forms, and non-commercial contexts.

All of these projects were instrumental and taught me how to work with tension, structure, and improvisation. At the same time, there was a growing need to introduce something more rigid and mechanical — machine-driven rhythm — and to bring abstract language and text into the sound. Doctor Bugg emerged exactly at this intersection: industrial hip-hop as a framework where machine pulse, spoken text, and instrumental noise can coexist. It allowed the intensity and unpredictability of instrumental music to be transferred into a form where language becomes an active rhythmic force, not just a narrative layer.

How would you say the ongoing war has influenced your creative process, both emotionally and practically?

On one level, the war has radically sharpened my focus on existential questions. It installs a filter that strips away the everyday and the merely personal, forcing attention inward — toward sensations, thresholds, and whatever is harder to destroy. At the same time, it constantly reminds you of how fragile and temporary everything is. This tension — between searching for inner support and witnessing collapse — has become a core condition of my creative thinking.

Practically, the war eliminates the illusion of “later.” When a country is at war, the planning horizon contracts to a few months at best, and postponement begins to feel dishonest. This creates a brutal clarity: ideas either materialize now or disappear. Alongside this a growing awareness of the need to exit a post-colonial cultural and mental state as quickly as possible comes. That calls for more Ukrainian music, more Ukrainian language, more events, and more autonomous meanings produced here and now.

What can you tell us about the production process for your new EP Осінь настала зненацька (Autumn came unexpectedly)?

The EP emerged during a period when song-based material was actively transforming into a live performance form. Instead of treating tracks as isolated units, the focus shifted toward continuous flow: texts, heavy industrial loops, noise guitar, and saxophone improvisations fused into a single stream with its own internal dramaturgy. The logic moved away from individual songs toward the architecture of an entire performance.

At the same time, there was a clear transition toward a heavier, more physical electronic sound. This created a sense of instability — the songs were being dismantled and reassembled. It became important to document this phase before the material was fully deconstructed and absorbed into the live system. The EP functions as a snapshot of that moment.

The album tracks later became the core of live performances at last year’s Strichka and Brudny Pes festivals. In their album form, these tracks will most likely no longer be performed live. However, as an energetic and structural foundation, they continue to partially underpin the new live program — not as fixed compositions, but as compressed sources of tension and momentum.

Autumn shows up less as a season and more like a permanent nervous state—exhausted, vigilant, irreversible. Was that sense of no-return something you were consciously composing toward, or did it emerge naturally as the record took shape?

Autumn here is associated with the paintings of Giorgio de Chirico — a suspension of time, a liminal state, a passage rather than a season. The title of the EP comes from a phrase in one of the tracks and captures the emotional condition that dominated the entire process of working on the release.

photo by Yurii Dyban (Xerxerash)

There’s a lot of bodily fracture and insect-like mutation in the imagery—identity becoming somatic and painful. Do you think of sound itself as a way to deform the body, not just express it?

Corporeality is the extreme expression of mental concentration — the body as a materialized substrate of a viscous mental state. Sound doesn’t translate ideas into feelings; it condenses them until they acquire weight, tension, and physical resistance. In that sense, sound functions as a way to deform the body, because the body is already a dense, overstimulated manifestation of thought. Repetition, distortion, and noise don’t impose violence from the outside — they expose what is already unstable, concentrated, and prone to glitch.

The imagery of fracture or insect-like mutation follows the same logic. Insects, especially beetles, function almost as totems — embodiments of a mechanistic, materialized mind. Within Doctor Bugg, sound becomes a tool to push this condensation further, forcing the mental into the somatic and making it unavoidable in physical space.

Therapy, faith, media, and myth all blur together on this EP, often feeling more controlling than healing. Are you questioning the systems we use to make sense of ourselves, or suggesting that meaning itself has become unstable?

For me, the meditation of a medieval alchemist, Freud’s drug-induced visions, Timothy Leary’s experiments, and artificial intelligence — all these constitute phenomena of the same magnitude: equal in their desire to understand the world, and equally imperfect because of the world’s fundamental unknowability. There is a strong attraction to scientific thinking here, combined with a parallel pull toward agnosticism.

Instability, glitches, and deviations offer the clearest way to understand how anything functions — whether an organ, a psyche, or a system. It is precisely in cracks and failures that underlying mechanisms reveal themselves.

How would you describe the post-punk and hip-hop scene in Ukraine?

I don’t follow every new release in the Ukrainian scene — my listening still leans more toward English-speaking musicians or instrumental music. Within Ukrainian hip-hop, there are interesting texts, but the beats often feel too jazzy or funky for my taste, and that does not resonate with me.

The post-punk scene — or what is labeled as post-punk here — is more familiar through direct contact with the Erythroleukoplakia Records community and through live shows in clubs like Otel’ and RVRB. What feels important is that this is a genuinely active and living community, with a pool of artists beginning to sound more confident and sonically precise.

If we look at releases from other genres, Ragapop resonates with me. Among recent streaming releases, Саундтрек до порядку денного by Ship Her Son stood out in particular. And live audiovisual performances of the artist Ujif_notfound also appear interesting.

Are there any releases from the past four years that have captured current events in a significant way for you?

I believe art often loses depth when it tries to react to events in real time. Some artists can capture the zeitgeist with precision — I can’t, and I don’t aim to. That role belongs rather to literature, journalism, and political analysis than to music.

It seems this kind of work is most effective at the overlaps of genres and disciplines — for example, in what Opera Aperta is doing.

What does it mean for you to be Ukrainian?

Recognizing a fundamental difference and the necessity of further separation from colonial ties. Thinking and speaking in Ukrainian. Supporting the Armed Forces of Ukraine.

photo by Yurii Dyban (Xerxerash)

Which book / film / album / song / traditional dish / podcast / blog / artwork / building / meme best captures Ukraine for you?

The question could be reframed as: what personally embodies or restores a sense of belonging to Ukrainianness. Like many people in Ukraine, I’m still going through the process of shedding the aftereffects of Russification and a colonial past.

In literature, it would be the body of work by Geo Shkurupii. In cinema, The Lost Letter (Propala Hramota) by Borys Ivchenko. As a song, Vopli Vidopliasova’s “Tantsi”. As a dish — borshch.

In visual art, the paintings of Mariia Prymachenko and David Burliuk. In architecture, the Pyatnytska Church in Chernihiv, built in the 12th century, and the sarcophagus over Unit 4 of the Chornobyl Nuclear Power Plant. And as a song-meme, “Bula v mene parova mashyna” in the spontaneous performance by Yaryna Kvasnii — something fragile, persistent, and deeply rooted.

FEBRUARY 8, 2025 – BERLIN

Photo by Yana Pylypchuk

I am Axxi Oma, but friends call me Axxi. Right now, I am a music producer and electronic live act. I could describe my background as a self-taught musician driven by her passion for sound design.

You were born in Kharkiv and are now based in Berlin. How has displacement shaped your artistic language?

I have to admit that in Berlin I was born as a producer. My fear of technologies was beaten by the example of female music producers I met here. Of course, forced migration has been a big trauma for me. Even though I feel very well integrated, the lyrics I come up with and the topics I dedicate my songs to are often connected to home. I avoid focusing my artistic identity around displacement, but it’s a big part of me as a person.

What brought you back to Axxi Oma as an electronic project?

For around a year, I put my solo project on stop. I never wanted to quit it completely, but I didn’t feel the energy to finish new songs and didn’t understand what my style was. During this year, I was working on several theatre projects. There, I felt free to make anything I wanted: it wouldn’t be released under my name, so it wouldn’t belong to me. In this period, I was singing and playing piano, being fully acoustic. I was lucky to work on one theatre play with Iryna Mavka. I was watching her pressing buttons on her loop station, a mystery box turning her unique voice into a choir. One day, she called me for a talk to tell me that she was about to leave the project, and suddenly she gave me her loop station with the words: “In the beginning, I had people who believed in me. Now I believe in you.” After that, I started learning, and one day I was ready to produce, mix, and release my own songs, and I am playing them live, still using the very same loop station.

Your debut EP Planets and Gods imagines a fictional, non-religious culture. Why was it important for you to distance yourself from reality while still speaking about it?

This EP was written in Amantea, a town in southern Italy. It was during a La Guarimba residency, and the organisers did everything to make us feel the local context. I was open to getting inspired by Calabrian culture, but I wasn’t ready to describe it the way a Calabrian would. Imagining a fictional culture was my way to stay in a safety zone, without taking the risk of appropriating Calabrian traditions.

The EP blends folklore with science and cosmic imagery. Do you see those worlds as connected?

Well, in my head, everything is possible. Apart from that, I am secretly a rationalist.

The track Hunters suggests that pacifism doesn’t prevent violence. Was that a difficult realization to put into music?

Honestly, yes. All I write is symbolic, and who the hunters are, what the old mountain and the sun are, depends on your interpretation. I was looking for a balance between my political statement, which I hide behind the song, and the space for speculation about what the song actually means.

Your song White Hole, featured on the Дім Home fundraiser compilation, describes existing as a hypothesis or cosmic error. What does the white hole symbolize for you, and why was it important to sing parts of White Hole in Ukrainian?

I was reading Hawking’s Brief Answers to the Big Questions and imagined how weird it feels to be a white hole: you are a phenomenal cosmic body, but no one is sure if you exist. My childhood was shaped by bullying at school; I constantly felt unheard and unseen, but deep in my heart I knew there was something cool about me. The Ukrainian part is the most personal for me. There, I question my own existence and the voices I was hearing my entire life that made me similar to a white hole. The line “I wake up from a big explosion” describes myself waking up from the explosions in Kharkiv, and the white hole being born from a Big Bang.

Your work is deeply collaborative, especially with Ukrainian artists in Berlin. How important is that community?

It’s hard for me to imagine my life without the Hotel Continental and Cultural Workers Studio communities. There, I met creative people who share my pain and deeply connect to the context of my art. These people make me feel at home, no matter where I am.

What do you hope listeners take away from your live performances?

I want them to lose their focus after the first 10 minutes of my show and dive into themselves. In this state of mind, new ideas are being born, and the body gets the energy to turn them into reality. That’s exactly why I hate making pauses between songs — I don’t dare to break this trance.

What does it mean for you to be Ukrainian?

For me, it means sharing the pain, love for our land, and knowing your place. I am not the best example of a Ukrainian; probably leaving Ukraine is not the best thing I did for my country. If I decide to stay abroad, my place is to talk here about Ukraine and to make sure our voices are being heard.

photo by by Anita Kopylenko

After four years since the full-scale invasion, what are your expectations from the current peace talks?

The last years have made me pessimistic about any peace talks. I don’t believe in an “instant peace” either, russia’s current war crimes don’t look like the finishing phase of the war.

Which book / film / album / song / traditional dish / podcast / blog / artwork / building / meme best captures Ukraine for you?

For me personally, nothing captures Ukraine better than Ukrainian stand-up. I am a big fan of Pidpilnyi Standup, and I feel like during the full-scale war humour is crucial to survive these times.

For those who don’t speak Ukrainian, I can recommend DAKH Magazine about contemporary Ukrainian art.

An absolute classic is Sergey Parajanov’s film Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors. The costumes, colours, and music by Myroslav Skoryk shaped an absolute masterpiece.

FEBRUARY 8, 2026 – UKRAINE

Photo by @whxplashh

Kateryna (drums): To be honest, the story isn’t very romantic. I just started playing: initially on the guitar, then on the bass guitar, and finally found my instrument—the drums. For me, forming a band was just something fun!

Anna (bass): The urge to create something of my own started when I was a kid—that’s why I begged my parents to sign me up for piano lessons. After four years of lessons, unfortunately, my initial desire remained unfulfilled, and the high demands of daily practice and years of independent study killed my interest in being involved in music in any way.

In the end, despite my unsuccessful experience in the past, my passion for music was renewed at the end of middle school, and in high school, I managed to earn enough money from my first job to buy my first guitar and combo amplifier.

Later, realizing that the technical requirements of playing the guitar did not match my own preferences in terms of sound production, I turned my attention to the bass guitar, which turned out to be a very successful decision. Before creating the band G.Inc with Kateryna, we spent hours together learning various instruments and making our first attempts at playing music. І also managed to be part of various bands on the local underground scenes in Chernivtsi and Vinnytsia.

Hanna (dj): I have been involved in music for a very long time—since I was five years old. At first, it was a choir at the Rivne Palace of Children and Youth. That’s where I started singing and playing the piano. Then I went to music school to study piano, so I was studying both at music school and at the Palace of Children and Youth. I was always drawn to it, and I enjoyed doing it anywhere and anytime.

As a teenager, I started learning to play the guitar on my own. In tenth grade, for a while, I even played bass guitar in a band with a guitarist and a drummer, who, by the way, later formed a band that is no longer active but is quite well known on the contemporary Ukrainian underground scene. During my university years, I focused on writing electronic music, and the DJ console became just a way for me to present it.

How would you say the ongoing war has influenced your creative process, both emotionally and practically?

Kateryna (drums): It can be said that the war directly initiated the creation of the band. Unfortunately or fortunately, it was the beginning of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine that led to the start of G.Inc’s musical search, initially as a bass and drum duo, but it undoubtedly still influences the band’s work as a trio.

The war made us realize that we only have one life, and that putting off our plans, dreams, and ambitions until some uncertain “tomorrow” would be a fatal mistake.

photo by @S.Yaskiv

What can you tell us about the production process for “Alga”?

Hanna (dj): When I joined the band, Alga was already a finished song in terms of bass guitar and drums. In the summer of 2024, the girls invited me to play with them at the “Brudnyi Pes” festival, even though we weren’t officially together as a band yet. Before the event, I really wanted to create the electronic parts, so I worked on it for several days without a break. The process was very interesting, but not easy at all: the parts were not repeated anywhere, and the song is quite long, so I had to come up with something new while trying not to lose the foundation.

As for the mixing, several people were involved, and the song passed from hand to hand, but we couldn’t achieve the bass guitar sound we wanted due to the recording method we chose. Perhaps this song was meant to be exactly as it is.

In terms of Deviation, its two tracks “Libido” and “Mortido” are often seen as opposing forces—life drive and death drive. Did you consciously frame the EP as a dialogue between these two states, or did that tension emerge naturally during writing?

Anna (bass): Indeed, the title of the EP and the songs on it were determined conceptually in advance. Since the songs are of equal length, I wanted to use the title to highlight the equivalence of opposing life vectors. However, despite the title of the song “Libido,” which, according to psychoanalytic theory, is positioned as a desire to preserve life, and outside of the psychoanalytic context has a positive connotation, the lyrics of the composition additionally describe the burden of personal experiences in the flow of life. “Mortido” is a darker song in terms of sound, which is what inspired the title, and the lyrics explore the issue of death in more detail.

In “Libido,” trauma eventually becomes “намистом” (a necklace), something worn rather than erased. Do you see memory and pain as creative material, or as something you’re trying to outgrow through music?

Anna (bass): The processes described are interrelated and integral parts of each other. Internal experiences and traumas, especially in the debut release, were indeed the basis and inspiration for writing the music, while the lyrics are a reworked substrate of rethinking and reliving previously experienced, sometimes painful and emotionally intense experiences. In the new material, the lyrics cover increasingly broader areas of personal experience.

Are you still currently based in Chernivtsi and how would you describe the music scene there?

Anna and Kateryna are from Chernivtsi, and Hanna is from Rivne. Now they all live in different cities: Anna in Vinnytsia, Kateryna in Lviv, and Hanna in Kyiv.

Kateryna (drums): Chernivtsi definitely has the conditions for studying music. There are music schools, teachers, studios, etc., but the community of musicians is shrinking, with a few exceptions. Many young musicians have left the country, so even ordinary teenage bands have become much less common, which is sad. There are not as many women who love music as there are men, and because of mobilization, they are putting their studies on the back burner, which is a logical and sad development in this case.

We also have more or less regular apartment concerts, musical and literary events to raise money for the front, and even less regular local festivals. We also traditionally hold the “Renaissance” festival on City Day, which in recent years has brought together exclusively local bands or bands from neighboring cities. The festival is competitive and funded by the city council, which is also very encouraging. However, there are very few venues. Concerts are mainly held at the rehearsal base and in the so-called rock club behind Chernivtsi University. Our audience is always hungry for more.

Are there any releases from the past four years that have captured current events in a significant way for you?

Kateryna (drums): In 2023, the Lviv band Mauser recorded the hardcore EP “One Day.” The band’s vocalist serves in the Armed Forces of Ukraine, which is reflected in the lyrics of the entire album, and the musical dynamics of the album complement the psychological tension. At the same time, due to the fast tempo of the album and its genre characteristics, the release turned out to be very exciting and, for me personally, captivating and inspiring. Perhaps it is this combination of energetic music and lyrics that raise the themes of conformism, violence, military service, and justice that is a good representation of the Ukrainian spirit.

What does it mean for you to be Ukrainian?

photo by @S.Yaskiv

Kateryna (drums): In our understanding, being Ukrainian means “being” no matter what. Over the past four years, the issue of Ukrainian identity and nationality has become extremely important in the minds of all citizens, and belonging to the Ukrainian ethnic group is particularly felt in contrast to European life. When you live in a country where people die every day, you stop worrying only about yourself and your own future.

Now, the well-being of your loved ones, friends, colleagues, and, of course, soldiers depends on you and your efforts. War does not give you the right to be an individualist, and without a community, it becomes extremely difficult to survive. The latest news reports that residents of Kyiv’s condominiums gather together during blackouts, cook food over an open fire, and dance to music at temperatures of -20 degrees Celsius. Being Ukrainian means being human, no matter what.

How are you coping with the winter conditions?

Kateryna (drums): It all depends on the region. Although there is no direct correlation between a city’s location and the amount of light it receives, some cities have a much harder time than others. Take Kyiv, for example. Just a few weeks ago, residents of the capital were draining water from their radiators at home because they were bursting from the extreme cold. Because charging stations are more of a luxury for Ukrainians, people have to endure the cold both outside and at home, often without even being able to use hot water or gas. This period also coincided with the longest nights of the year, which is particularly demoralizing.

After heavy shelling, everything gets much worse — there may not be enough electricity to turn on the lights for 2-3 days in a row, and people have to sleep in the same clothes they went outside in. However, energy sector workers continue to work even during this time and quickly repair substations, so the situation between shellings is usually better.

Four years into the full-scale invasion, how do you expect the situation to evolve, do you have any faith in the “peace negotiations”?

Kateryna (drums): It seems that throughout the entire full-scale war, no one has been able to accurately predict the course of events on the front lines or at the negotiating table. However, to be honest, any realistic predictions of events are still rather pessimistic.

At the beginning of the full-scale war (the first 9 months to a year), Ukrainians were much more optimistic about the resolution of the war. For example, many people believed that Ukraine would be able to break up the russian federation into the republics that it had occupied throughout its existence. Obviously, after four years of active warfare, when the enemy has firmly entrenched itself in its positions, when new gatherings are held every day to help families who have lost a son or daughter, when every day during a minute of silence for fallen soldiers you remember more and more names and faces, and the map of occupied territories is growing to Ukraine’s disadvantage, the prospect of destroying russia seems like a fairy tale.

However, all people in Ukraine are divided into two groups — those who are doing something in the army and those who are doing something for the army. It is almost impossible to live a day without helping the Armed Forces of Ukraine, at least financially.

Which book / film / album / song / traditional dish / podcast / blog / artwork / building / meme best captures Ukraine for you?

photo by @S.Yaskiv

Anna (bass): In terms of music, one of the best examples for me is the album Shabadabada by the band Mertvy Piven. This album includes two songs with lyrics based on poems by Taras Shevchenko in a lively arrangement, while the lyrics of “Beautiful Karpaty” refer to numerous works whose events unfold in the middle of the Ukrainian Carpathians — an integral part of Ukraine’s landscape and culture associated with the region.

Throughout the album, the lyrics raise various moods of human existence — from humorous descriptions of the issues of mature age and romantic experiences to raising existential experiences of the meaning of human life and melancholic moods. The song “Holodno” deserves special mention, as its lyrics, in my opinion, best describe the last weeks before the full-scale invasion. It is particularly striking that the album was released in 1998, long before the war, but remains relevant today.

Hanna (dj): It is difficult to encapsulate the entire Ukrainian context in one thing. But from the books I have read, Artem Cheh’s “Who Are You?” comes to mind. For me, this text is about the constant question “Who am I?” — both for an individual and for society as a whole, about memories that we don’t always want to inherit and trauma that is passed down from generation to generation, about responsibility.

In my opinion, the essence of the Ukrainian experience is constant inner work on oneself, not always easy maturation and, ultimately, an attempt to look at everything with honesty towards oneself.

FEBRUARY 11, 2026 – KYIV

photo by @lessnightlights

My name is Denys, i’m 23 and was born in Kyiv, Ukraine. My project name is Pencil Legs and i’ve been making these bedroom pop/indie rock songs for it since 2021. I started playing guitar and listening to a lot of 90’s and 00’s rock music when i was about 12. I got FL Studio when i was 14 and started making lots of bad music for my different projects and now i am where i am.

How would you say the ongoing war has influenced your creative process, both emotionally and practically?

It definitely influenced me but not in a direct way. I “officially” started this project in April 2022 when i came back to Kyiv with my parents from the west of Ukraine where we were living for 2 months shortly after the war started. I had this project in mind before the war, but started making more and more songs to sort of distract myself from all the messed up things happening, so the songs were not so much about the present reality, but more of an escapist introspection with lots of nostalgic images and childish sentiments. I don’t think i was making these songs with this mood intended just to escape the present necessarily, i would’ve probably do the same if the war never started in the first place, but it definitely helped me cope with all the war-related hard stuff.

“Empty Shopping Mall” feels very still but also unsettling. What was it about that kind of liminal space that pulled you in emotionally, rather than, say, a more obviously dramatic setting?

The liminal space thing was inspired by a literal scene in my life when i was waiting for my friend in a half-empty shopping mall on the working day and i was literally sitting on the bench in front of one of the stores and writing down my feelings.

In the song you sing “Everything is great / But there’s always something off.” That line feels like it could describe a lot of your music. Do you think that sense of “almost-okay” is something you’re consciously chasing, or does it just keep showing up?

I guess it’s just how i feel most of the time in general. A lot of the time, even if everything IS great in my life, there’s always one, or two things on the periphery which bother me. I’m just a very anxious person i suppose.

You mentioned seeing yourself in Beckett’s Watt, especially in the way language falls apart. Do you feel like songwriting is a way to regain control over language, or to lean into its failure?

I identify heavily with Beckett’s writing and with this specific aspect of a declining language and lack of communicative skills and when it comes to my own songwriting, i hardly ever gain control over the language at all, it’s always a struggle, but at least i have more time to come up with things i actually want to say as opposed to communicating with people on a daily basis. For me music is the best way to express what i feel, not speaking directly to other people. I also don’t like opening my mouth in general if it’s not singing.

photo by @lessnightlights

A lot of your track titles — “Old Room”, “Out of Place”, “Rag Doll”, “Empty Shopping Mall” —suggest being stuck, misplaced, or passive. Do you think of Pencil Legs as a project about observing life from the sidelines?

I usually write from my own perspective and often it is very literal and light on metaphors so it mostly is about me feeling stuck, misplaced and passive, i feel like my life is just existing on the sidelines.

On Fruit Under the Tree, many tracks are very short, almost fragment-like. Do you see those songs as complete statements, or more like snapshots from a longer inner monologue?

Probably the latter. Most of my songs are not about one specific topic or a feeling, rather a diary note or, yeah, a snapshot, a sketch of a set of emotions i feel in the moment of writing. My new music though takes a slightly more mature approach in this sense, they do feel like complete statements sometimes.

You’ve talked about moving away from lo-fi aesthetics and exposing more “roughness” in your sound. Is this process more technically scary or emotionally uncomfortable?

It’s both technically scary cause i’m learning and making everything by myself sound-wise and emotionally uncomfortable cause i can’t really hide behind this lo-fi curtain anymore, my voice and lyrics mostly sound very clean right now, with less tape simulators and reverb. But it is something i consciously want to do and i’m still not even fully sure why and why now but i just felt like i should try.

There’s a quiet tension between humor and sadness in your work. How important is irony or self-mockery in keeping these songs from becoming too heavy?

I think that this is a hallmark of our time in general, people are to scared of being 100% sincere so they hide behind these layers of irony and feel safe of being judged. And in my life and my songs included i often use this strategy for the same reason.

Your music often feels very visual, almost like walking through empty rooms or half-lit spaces. Do you usually see images first and then write music, or does the sound come before the scene?

I think as soon as i find a riff or a chord progression i like on the guitar or a lyric idea is start imagining visual images right away which helps with the further development of the song, i think a lot of people can relate to that though, these processes usually go hand in hand.

As you work on the next album and move further away from lo-fi, what do you hope listeners will notice that they maybe couldn’t hear clearly in your earlier releases?

In the first two albums i used to pitch the whole master of the song 1 half step up and it made my voice sound a little closer to a female voice. Now i don’t do that, so listeners are probably gonna notice that and also i just sing more clearly and not mumbling as much as i used to.

photos by @lessnightlights

Are there any releases from the past four years that have captured current events in a significant way for you?

There’s a song called Now Run which captures it the most and while not being directly about war, it’s about this apocalyptic feeling and about feeling pressed against the wall and unable to save yourself form something you’re not in control of.

What does it mean for you to be Ukrainian?

It means being constantly challenged and oppressed just because you want to keep your own identity, freedom and a right for change for the good and choosing your own future. There’s always someone who will keep trying to ruin that for us.

How are you coping with the winter conditions?

Spending time with my girlfriend and our cats. This year is especially cold so the hardest part is to get enough warmth everyday both physically and emotionally.

Four years into the full-scale invasion, how do you expect the situation to evolve, do you have any faith in the “peace negotiations”?

I don’t know if i have any faith in anything at all now but I always prepare for the worse. I only know that Trump and Putin are complete morons.

Which book / film / album / song / traditional dish / podcast / blog / artwork / building / meme best captures Ukraine for you?

I’ll say the album Selo by Cukor Bila Smert just cause i’ve been relistening to it a lot lately.

NEW RELEASE

kyïvite ~ broadcast 13/02/26

Format: radio broadcast.

Samples: archival recordings from Filaret Kolessa’s folk expedition.

Recorded by: Filaret Kolessa, Lesya Ukraïnka, Klyment Kvitka.

Singers: Mykhailo Kravchenko, Platon Kravchenko, Antin Skoba, Yavdokha Pylypenko, Ostap Kalnyi, Stepan Pasiuha, Ivan Kucherenko.

Collage Y ~ Mechanical Voice

Mechanical Voice is a collection of small sonic worlds, playful and slightly uncanny. Collage Y blends experimental electronics, ambient soundscapes, jazzy fragments, and neo-folk textures into brief, vivid pieces that feel both meditative and restless. Everyday moments drift into surreal scenes, rhythms wobble and repeat, and machines seem to quietly respond. Fragmented, curious, and quietly imaginative, the album unfolds like an audio collage—inviting close listening and wandering attention.

Dub User ~ Echoes from Analog Void

Echoes From Analog Void drifts through deep dub, roots reggae, and electronic psychedelia, balancing weighty basslines with spacious, sun-washed textures. Created in Odesa during one of the harshest winters since the full-scale invasion, the album carries a quiet resilience—warm, reflective, and tinged with blues. Tracks unfold slowly and deliberately, orbiting themes of solitude, gravity, and boundlessness, where analog echoes blur into cosmic dub meditations. Grounded yet expansive, this is music for long horizons and inward journeys.

Hillmer ~ FIDĒS

FIDĒS is a melodic techno journey built on trust, flow, and restraint. Crafted in Kyiv, the album pairs infectious grooves and luminous synth work with a subtle human presence—snatches of speech surface and dissolve, as in the opening Kowloon, grounding the music without breaking its spell. Each track unfolds organically, guided by minimal structures that evolve just long enough before giving way, never overstaying their welcome. Shaped by Hillmer’s performances at Brave! Factory and Strichka, FIDĒS moves effortlessly between the dancefloor and inward listening: dreamy, uplifting, and quietly confident. Somehow ironically, considering Ukraine’s martial law, these tracks feel tuned for late-night floors and inward listening alike, where momentum meets reflection.

Khrystyna Kirik ~ State of Latitude

State of Latitude is an album by Khrystyna Kirik dedicated to four Ukrainian landscapes transformed by war: Sviati Hory, Syvash, Velykyi Chapelskyi Pid, and Kamianska Sich. Each track is rooted in a specific territory affected by destruction, occupation, and long-term ecological disruption.

Originally developed as an audiovisual installation during the Echoes of the Earth residency at ∄ in Kyiv, in collaboration with u2203 studio and ecologist Anna Kuzemko, the project takes the form of a sound document. The album translates environmental change — damaged ecosystems, altered biodiversity, disrupted natural rhythms — into musical composition.

The music combines electronic textures, environmental sound, and research-based observation. Ecological knowledge gathered through interviews with Anna Kuzemko informs the structure of the work, grounding artistic interpretation in scientific understanding.

A traditional Ukrainian song, “Oi, Bozhe, Bozhe, z takoiu hodynoiu…” (from Songs of the Ukrainian Steppes II, 1996, by Hílka), appears as a recurring motif — once freely sung across the steppe, now returning as a distant, transformed echo.

State of Latitude treats nature not as a backdrop to war, but as a living body that absorbs violence and carries its consequences long after active fighting ends.

Artwork by Myk Rudik (u2203), under the artistic direction of Alen Hast, is based on archival imagery and ecological data collected in the field, merging documentation and imagined landscapes.

Chloe Landau ~ Dreamhouse

Chloe Landau is a Ukrainian singer and a key figure in Kyiv’s underground scene. Her sound blends grotesque, confessional lyrics with a strange, at times heavy sonic palette, charged with the glossy, glamorous energy of early-2000s pop culture. Chloe is a fragile bimbo-girl singing about war, codependent relationships, and death.

Chloe is the songwriter behind all of her music. Her lyrics are poetic, romantic, and apocalyptic — written entirely in Ukrainian — marking the emergence of a new generation of Ukrainian songwriters and performers.

Over the past two years, Chloe has performed at MOFO (Porto), Pandora Gallery (Berlin), Open Secret (Kyiv), the Konstruktsiia Festival (Dnipro), and at the birthday event of ∄ (Kyiv).

Her debut release on Standard Deviation, Dreamhouse, is an almanac of her work from the past year. Koreia was chosen as the first single, as it most clearly captures the tension between fragility and control, addressing war, codependency, and inner collapse through Chloe’s deeply personal presence.

The album unfolds like a multi-room dollhouse: in one room, she cuts the umbilical cord between herself and God; one floor above, Chloe becomes Britney Spears, dancing for us with knives. Dreamhouse captures the feeling of a world falling apart — breaking down more violently with each passing day — yet Chloe remains herself throughout: sensitive, tender, and, in some ways, deliberately infantile.

Delirium ~ Спіраль Мовчання

Спіраль Мовчання (Spiral of Silence) is a dark, intimate EP where post-punk, darkwave, and gothic new wave intertwine with raw Ukrainian poetry. Delirium move between mechanical pulse and fragile melody, letting drum machines, organ drones, and shadowed guitars frame stories of memory, loss, and quiet resistance.

From the circular mantra of “Спочатку” to the fading heat of “Літо,” the haunted recollections of “Слов’янськ”, and the stark grief of “Втрата,” these songs feel like fragments pulled from lived experience, personal, heavy, and unresolved. Repetition becomes ritual, silence becomes pressure, and absence speaks louder than noise. Спіраль Мовчання unfolds as a somber reflection on time, war, and what remains when words begin to fail.

Amphibian Man ~ Metal Goes Surf Vol. 2

Metal Goes Surf Vol. 2 is Amphibian Man at full throttle and loose at heart—a high-energy collision of surf rock shimmer, metal heft, and psychedelic momentum. Built on crashing riffs, rolling rhythms, and melodic leads that cut like saltwater spray, the album rides a fine line between precision and play.

Written as much to recharge as to release, these tracks feel like motion therapy: fast when they need to be, spacious when the wave opens up. From the punchy rush of Be Quick Or Be Wet to the long, drifting finale Long Lost to Where No Wave Goes, the record surges forward with joy, grit, and sunburned intensity. Heavy, catchy, and unpretentious, Metal Goes Surf Vol. 2 is an instrumental escape—music to wipe out, get back up, and paddle out again.

Yehor Tymchenko ~ камера вільсона

камера вільсона‘s (Wilson chamber), is a collection of short, fractured scenes—lo-fi electronic sketches where dub echoes, industrial grit, and illbient textures collide. Yehor Tymchenko treats sound like particles passing through a cloud: beats crack and dissolve, rhythms stumble, and melodies surface only briefly before fading out.

Built from everyday observations, deadpan titles, and uneasy humor, the album moves between detachment and quiet intimacy. Tracks arrive abruptly, linger just long enough, then vanish, forming a diary of motion, fatigue, and return. Minimal, restless, and deliberately imperfect, камера вільсона documents invisible processes—personal, social, and sonic—made briefly audible.

Rushnichok ~ Nightingales of Ukraine. The Best of Ukrainian Folk Music

Do you know that Ukrainians are one of the most singing nations and their songs are most melodic and beautiful in the world. The roots of Ukrainian songs go deep in the olden days. Ukrainian culture provided the basis for the formation of the later Slavic cultures of Russia and Belarus. This album of a popular Ukrainian folk songs is a wonderful introduction to Ukrainian folk music. Rushnichok was founded in 2005 by composer, producer and arranger Oleksii Zakharenko AKA Origen and two Ukrainian National Opera House singers: Tatiana Lubimenko, and Miroslav Grishenko. You can easily guess that their masterly performance is at a high level as well as music and arrangements. Not sure? Listen this album.

Timur Basha (inc. Dana Kuehr Remix) ~ Sluhay & Dyakuy (BM21)

The long-standing artistic director, resident DJ, and co-founder of Closer Kyiv, Timur Basha steps up after 15 years of producing in the shadows with his first-ever solo EP. The daughter of Timur’s best friends (Karine + Shakolin) gave us these words to accompany the record on its journey into the world: “sensitivity, serenity, loyalty, hope, luck & love…<3”

ken=en ~ простій

On простій [Simple], Kyiv producer Pavlo Okhrimchuk (ken=en) frames inactivity as a space for drift and discovery. The album moves freely between experimental electronics, playful genre detours and melodic intuition, treating form as something provisional. Piano lines rub against drum’n’bass momentum on “немає кращого місця на землі ніж рідний дім”, [There Is No Better Place on Earth Than Home] while “у кавоварці була риба!” [There Was a Fish in the Coffee Maker] folds field recordings into a brief, surreal aside.

Track titles oscillate between abstraction and offhand literalism, mirroring music that feels casually assembled yet carefully balanced. Even at its darkest [“прірва” (abyss), “бобиль” (bobyl)], простій resists heaviness, maintaining a lightness of touch and a quiet sense of joy. It’s a restless, open-ended record—less about resolution than motion, curiosity, and the pleasure of trying things out.

Shadowsun ~ Architecture Dreamscape

Architecture Dreamscape unfolds like a slow walk through a half-forgotten megastructure at the edge of memory. Across dense drones, cold ambient swells, and vast spatial echoes, Ukrainian artist Shadowsun sketches a dystopian inner city where concrete breathes, storms linger, and silence presses with weight. Tracks drift between monumental stillness and uneasy motion, blending dark ambient and space ambient into a single, immersive continuum.

Asyncronous ~ Selected Memories We Never Had

Asyncronous return with their third EP Selected Memories We Never Had – a refined continuation of the Ukrainian project’s signature blend of ambient and downtempo. On this release, their sound evolves into a more cinematic, immersive form, shaped by layered atmospheres, subtle melodic narratives, and deep emotional textures. The EP balances introspective mood with strong visual imagination, positioning Asyncronous firmly within the space between contemporary ambient, electronica, and film-influenced sound design.

This release marks the relaunch of Kashtan, a Ukrainian record label curated by Vera Logdanidi. After a pause caused by the full-scale war in Ukraine, Kashtan returns with its first vinyl release since 2022, dedicated to forward-looking Ukrainian electronic music beyond strict genre definitions.

Dronny Darko ~ Dark Shadows Across Disordered Mind

Dronny Darko returns with Dark Shadows Across Disordered Mind, an album exploring fractured cognition and brief episodes of clarity inside a collapsing internal architecture.

Broken corridors repeat in loops. Memory structures buckle, re-form, and collapse again, leaving only residual impressions. Shadows stretched across thought space, half-recognizable and already decaying. Coherence appears as a flicker, then dissolves back into interference.

Brooding low frequency pressure and layered drones move beneath granular textures and distant harmonic residue, shaping a labyrinth of unstable states.

Recommended for fans of introspective dark ambient, psychological isolation soundscapes, and cinematic drifting drones.

hjumən ~ Lifecycle_02-26

Hello, humans. This EP is about life. I mean, our lives are kinda senseless in general. Maybe somebody finds some romantic in this fact. I am not. I think it’s incredibly stupid. I want to live with sense. So, this release is one of my countless efforts to bring sense to my life.

Musically, this one sounds more aggressive and dark, but the melodic/harmonic base is still out there as well. Enjoy.

ZzuppamanN ~ IN MEMORY

IN MEMORY is a raw, unflinching requiem for Sumy’s underground — a city’s lost voices echoing through distortion, memory, and defiance. Born from gratitude to friends, fallen musicians, and the steadfast spirit of the Armed Forces of Ukraine, the album stands as both memorial and manifesto.

Across tracks like “Zori,” “Babylon,” and “Zakliattia,” the band drifts between dream and curse, light and ruin. “Antysanitaria” turns inward, confronting rot not only in the streets but in the mind — a searing confession of silence, complicity, and the slow burn of things left unsaid. In “Moskall,” the tone sharpens into open resistance, exorcising the ghost of empire and propaganda with a chant that is as much self-purification as protest.

Dedicated to departed Sumy projects — Ambulance, Nilsbory, Ploshchad Mopsa, Ampheteatre — IN MEMORY resurrects their spirit in feedback and fire. It is grief set to rhythm, anger shaped into chorus, and love for a scene that refuses to vanish. This is not nostalgia. It is remembrance as resistance.

58918012 ~ Soup

Hello, people! I hope you are all doing well. If you are reading this, then you probably know me and know that I like to push boundaries of my musical comfort zone further and further away. This album is one more of my personal challenges.

This time, one of my goals was to finish all tracks for the album as fast as possible. All work on the album took three days (maybe a bit longer). I think, at this point, it’s my own time-record. Probably, I can go faster, but what for? I like to make music as a meditation.

From the concept perspective, the album is called “Soup” because our lives are built of a lot of ingredients, and those are continuously boiling around and inside of us. Life itself is a soup, so to speak. Each track here is a part of a wider picture of life. Yes, they’re pretty sad or even dark in some way…but how could it be different at this point in time?

It sounds pretty warm and deep. It’s slightly rhythmical. I said slightly, because all drum parts are blurry here. Melodic elements are also in there. In any case, I hope you like it. As usual, thank you very much for staying with me. Stand with Ukraine! Peace ❤

VIEWING ROOM

(Gianmarco Del Re)