Sound Propositions is an ongoing, semi-regular series of conversations with artists exploring their creative practices and individual aesthetics, conceived of as a counter-narrative to a dominant trend in music journalism which fetishizes equipment and new technologies. Rather than writing copy that can just as easily have come from a press release or a catalog, this series tries to take the emphasis away from the ‘what’ and shine light on the ‘how’ and ‘why.’ You can find the previous eight interviews, as well as additional articles and features, here.

There’s a school of thought amongst field recordists that favors alienating oneself from the provenance of one’s recordings in order to hear the recordings with fresh ears, and to better respond to the sound as a material object (or sound object) in itself. This practice can make the reduced listening preached by Pierre Schaeffer and other musique concrète composers easier to attain, liberating the recordist from the memories and impressions associated with the time and place of the recording. It can also encourage a randomness that improvisers can use to generate tension and forward propulsion, as the artist must react in real-time and not depend on a detailed knowledge of what will be heard. On the other side of the spectrum, there are recordists who believe their work to be objective forms of documentation, a view especially prevalent amongst nature recordists but certainly not exclusive to them. Fidelity is the highest aim, and as such the medium is considered not for the characteristics it brings to the recording but only as a source of potential degradation. The Latin origins of the word “fidelity” betrays what is really at work in such cases, namely a faith that there is something which can be captured, and that the alleged interference of the medium will one day disappear completely through technological advances. Kate Carr doesn’t fit into either of these theoretical camps, neither distancing herself from her source material nor chasing after objectivity. Her work utilizes the personal associations she has with her recordings, and her own subjective experiences help to determine the shape and the affect of each of her compositions. The medium is something to be embraced, as both the listener and the listening medium is pre-supposed as being always already in the midst of things.

Kate Carr’s work is rooted in the emotional resonances and potentialities of sound. Her compositions play on these resonances through interactions with environmentalism and technology, her frequent travel often serving as a starting point for new projects. Her globetrotting may result in a growing list of places serving as imaginary settings for her work, but rather than (re)present these places as objective she relies on the subjective experience of listening (both her own and that of her audience) to harness the interaction of sound and place in ways that are nothing short of fantastic. Though some years she had released some digital works and CDRs in the glitch tradition, as wells a doing a fair amount of DJing, Carr found her voice as an artist with the founding of her label Flaming Pines in 2011. This coincided with a new focus on composing with field recordings and environmental sounds, as exemplified by that year’s Summer Floods. Themes of wandering, uprootedness and the search for home continue to animate much of her work, and her wanderlust has yet to abate.

We at A CLOSER LISTEN have watched Kate Carr’s career with growing interest since our inception. Return to New Caledonia was one of our Top Ten Field Recording and Soundscape albums of 2012, while her Songs from a cold place, documenting a pilgrimage to Iceland, was similarly honored in 2013. blue | green, her exploration of color and sound with Gail Priest revealed yet another side of Carr, demonstrating her capacity for productive collaborations, while Landing Lights proved her versatility, weaving together a diverse collection of tracks unified by a strong conceptual framework. Flaming Pines’ Birds of a Feather series showed us that Carr was thinking seriously about packaging, presentations, and the experience of listening. This is to say nothing of her eye for spotting talent, and in fact her excellent curation of the label deserves mention, which includes albums from Porya Hatami, Marcus Fischer, The Boats and Seaworthy. Still, last year’s Lost in Doi Saket/Overheard in Doi Saket, a soundmap and limited editions SD card release, was still able to take us by surprise and was voted our number two album of the year in addition to being recognized for best packaging and the year’s best field recordings.

We at A CLOSER LISTEN have watched Kate Carr’s career with growing interest since our inception. Return to New Caledonia was one of our Top Ten Field Recording and Soundscape albums of 2012, while her Songs from a cold place, documenting a pilgrimage to Iceland, was similarly honored in 2013. blue | green, her exploration of color and sound with Gail Priest revealed yet another side of Carr, demonstrating her capacity for productive collaborations, while Landing Lights proved her versatility, weaving together a diverse collection of tracks unified by a strong conceptual framework. Flaming Pines’ Birds of a Feather series showed us that Carr was thinking seriously about packaging, presentations, and the experience of listening. This is to say nothing of her eye for spotting talent, and in fact her excellent curation of the label deserves mention, which includes albums from Porya Hatami, Marcus Fischer, The Boats and Seaworthy. Still, last year’s Lost in Doi Saket/Overheard in Doi Saket, a soundmap and limited editions SD card release, was still able to take us by surprise and was voted our number two album of the year in addition to being recognized for best packaging and the year’s best field recordings.

Fabulations is Kate Carr’s most recent album (published by Soft Recordings), a further exploration of now familiar themes that nonetheless breaks new ground in the way it plays with concepts of fantasy, space, recording, listening, and process. The ten tracks that make up Fabulations are built from cores of recordings made in Marseille, Nice, Cefalù, Catania, Dublin, Belfast, Glasgow, Edinburgh, Dungun and Barcelona (though not in that order). Evocative titles help form images and a sense of place, often functioning as place markers while simultaneously gesturing towards a frame of mind: “Cold Trains,” “Sound Art in Barcelona,” “Under an ancient fort.” Other titles describe more a feeling or affect (“I felt better about everything in Dunquin,” “I remembered it all somewhere near Glasgow”) or an object being heard (“Broken sheep fence, gale,” “Bleeding Love (Bus Sicily)”). “In corridors a thousand years old” we hear resonance and diffusion, capturing the sense of space that defines these ancient passageways. Meanwhile “In Sicily I Slept In The Shadow Of A Rock” captures a similar sense of objective space, but the gradual evolution and subtle processing of the sounds captures more the feeling of the experience than of the place itself.

Field recordings are edited and arranged, often sounds are sought out in the moment of recording giving the act of recording an explicit compositional functioning. These sounds are mixed in such a way that there is no mistake that each sound environment was carefully sculpted. The crashing of waves, gently processed, is at a similar volume to close-miked rustlings and swelling guitar drones, or the rumbling of some object or another rigged with contact microphones. While one moment the guitar resonates, likely amplified through Direct Input, we may also hear the sound of the guitar, unamplified in the room the recording is taking place. Each impressionist scene may also function as a facture, revealing its process without sacrificing any of its power. As if to say, through transparency we can listen more closely to intention, more easily be swept away. The simple cut-up of the cover art is suggestive in this regard.

The term fabulation refers to inventing or creating fantasies, which is certainly something that Kate Carr excels at in her sonic compositions. Fabulation also has several distinct but related connotations, each offering a potential ways into to thinking about Carr’s work, each offering different insights and ways of listening. In literary theory, the critic Robert Scholes has used the term to describe work that experiments with form, content, style, and sequence, resisting categorization as realism or fantasy. Such works blur the distinction between the mundane and the fantastic, between the mythical and frightful. Fabulations similarly resists easy classification, and its minimal sound sculptures with their everyday noises augmented by at times unsettling sonorities suggests that Carr may have had this meaning of the term in mind. But we might think also of the French philosopher Henri Bergson, for whom fabulation was a function that takes our sense of being watched (or perhaps listened to, in this case) and transforms it, imbuing new images and objects with the power of collective, shared meaning.

The final track on Fabulations is a raw field recording made (presumably) on a bus in Sicily. There is no evidence of editing or processing of any kind, and Leona Lewis’ “Bleeding Love” is playing in the background, likely the pop hit of the moment entertaining the bus driver as they speed through winding seaside cliffs and mountain passes. Although the title ostensibly tells us all we need to know (“Bleeding Love (Bus Sicily)”) there is more than enough ambiguity to stoke the fires of our imaginations. Coming at the end of the album, our ears have been tuned to listen differently, so that even a cheesy pop song can now be heard as simply part of the sound environment, on par with the rustling of passengers, creaking of seats, and engine noises. To the tourist the scenic vistas, consisting of fields of wheat, of seaside cliffs and winding mountain passes, of volcanic islands and ancient cities, inspires a powerful sense of awe, of historical time as well as deep geological time. But perhaps the bus driver has driven this route many times and what is exotic and awe-inspiring to the outsider becomes oppressive and mundane. And perhaps our tourist has literally heard the song “Bleeding Love” or similar pop dreck at every bar and caffè she has visited. Even a simple juxtaposition of the sounds of a bus in the middle of the Mediterranean with the familiar sounds of English-language pop on the radio takes on unexpected resonances through fabulation. (Joseph Sannicandro)

We are honored to present not only this fascinating interview with Kate, but also to be able to share with our readers her new video “Street singing, Belfast,” an animated exploration of the streetscape in Belfast, Ireland.

INTERVIEW

Joseph Sannicandro: Can you describe how you came to develop your practice? What led you to sound?

Kate Carr: I’ve always been interested in sound and music; as a kid discovering graffiti and pop music were absolutely pivotal moments, and in doing so I found [ways] to channel some sort of emotional excess into something creative or at least exhilarating in terms of singing along to music. From there I’ve really taken lots of paths, I used to do a reasonable amount of DJing, I also ran an artist-run space with a bunch of people where we put on both gallery shows and music nights, and as part of that I did an installation work which incorporated sound. Then I went on to do a Master’s at university which introduced me to experimental music and it was really from then that I started to make my own sound pieces, so in lots of ways not that long ago. With my visual arts I always interested in the fantasies pop music offers us, the emotional efficacy of the medium, the escapism. I did a whole series on middle class white lesbians dressed up as rappers, as at the time there was great interest in drag kings (women dressing up as men as part of a stage act) in Sydney, and many of these women performed to hip hop songs, and I was interested really in why that fantasy was so potent, what was it about those sounds and that male hip hop identity which resonated so strongly. So definitely that wasn’t the most conventional introduction to sound work, but I do think those interests in fantasy, narrative, and the personal have stayed with me in terms of my sound work today.

In terms of developing my practice I started very much with Oval and the whole glitch scene. I loved that idea of the creative potential of error, but I was also always interested in the emotionality, nostalgia and subjectivism of sound, so my first album was really an exploration of these perhaps not immediately related ideas, and I glitched up lots of samples from very emotionally potent songs. Then I didn’t do anything for a few years as I was pretty busy working as a journalist. But in 2009 I did a project exploring in part the sonification of data, but combined again with samples from mainstream music which referenced ‘water’ which was the Listen to the Weather project, and following that I launched Flaming Pines to put out a record based on the pieces I collected for that project.

Since then I guess I would say I’ve remained interested in the emotional efficacy of sound, its direct relationship with the body, the creative potential of getting things wrong, and the imperfect. I’m very interested in the sonic experience of place and of new places, or unfamiliar places. I’ve travelled quite a bit now as part of my practice and I’m very interested in personal mapping, again with an emphasis on the subjective and error-ridden ways we do this particularly when we are somewhere new. I’m particularly interested in those moments of disorientation we experience when somewhere new, or in a new situation, and the surprising emotional and creative possibilities this opens up. I actually like to be lost in some ways, and I like to look at the ways we use sound or music to find ourselves or our way again.

That’s a perfect segue into my next question, as I’d like to discuss your work from Doi Saket, Thailand. There’s a strong argument for a non-representational way of listening to sound, not for it’s intended “meaning” but for what it is, its sonic materialism. But a project like yours from Doi Saket, especially, something so site-specific and evocative, relies on a certain level of representation, even if it also necessitates a kind of imagination on the part of the listener. The emotional engagement you’re after is perceptible by your listeners, yet it comes out of your own subjective experience of your object (in this case the sites in Thailand, your own subjective explorations of these sites). What is your approach to bridging this gap, translating it for your audience?

Yes I think there is a strong argument for the materiality of sound itself in terms of the listener’s experience of sound art and field recording. One of the things I find interesting and also don’t agree with from some field recordists is the way there is an almost religious belief in the power of field recordings to transport the listener to somewhere else, and that this place relates to the recording site. I don’t think necessarily the listener is transported to a place which in any way resembles the recording site and I think it is important to be aware of that as a field recordist. I can listen to recordings of mine, bad ones, better ones, and immediately remember what it felt like to take that recording and to be in the place. I always sit with my gear and listen as I record, or I usually do, so as soon as I hear those sounds I can remember exactly the site, how I felt, what was going on for me in my life and in that place. But that is not a relationship to that recording which is in any way transferable to the listener; at least I don’t think it is.

I think I’ve read two things fairly recently which have influenced my thinking on this. Salome Voegelin’s Listening to Noise and Silence: Towards a philosophy of sound art, which is very much centered on the view that meaning making of sound art is the result of the relationship between the listener and the sonic material, that the listener her or himself creates the piece almost anew through his or her listening, and I find this a compelling idea. I also very much like her discussions on listening to sound art and the ways this doesn’t generate new knowledges for her but, rather a sense of knowing about herself in relation to the sonic material and the time and place she herself produced through listening to it. For me my Doi Saket album is very much about the time, place and emotionality I myself produced through listening and recording Doi Saket and my attempt to convey something of that. But another set of ideas I’ve also found important stem from an interview with Hildegard Westerkamp which I read in Cathy Lane and Angus Carlye’s The Art of Field Recording where she talks about the need to ‘exaggerate’ aspects of a recording to draw the listener into a passionate experience of listening to the material.

Lost in Doi Saket (click for soundmap)

Lost in Doi Saket (click for soundmap)

So in terms of my Doi Saket release my opinions about this did influence the final form of the release. I never intended it to be a document which attempted to convey something essential about Thailand the country, or the people of Thailand. For me that would be a ridiculous project for spending one month in a tiny part of the country, and also an incredibly arrogant thing to do. What I was interested in exploring was what it felt like to exist as an outsider who did not speak the language in that place, with that soundscape for that period of one month. And because I work with sound I guess I asked myself what would that experience sound like if it could be distilled purely into the sonic. So in that sense there is certainly emotionality to it, residencies are actually very intense experiences and that one particularly was, being somewhere so isolated, incredibly evocative and beautiful was very special. Thailand remains my favourite place to record as I just felt the soundscape was so incredibly rich and it appealed immensely to me with its cacophonous mix of sounds: buskers, Thai pop blasting from various houses, the incredible noise trucks which drove by almost daily I think campaigning for elections or making announcements, the frogs, the scooters, the everyday hustle and bustle of the Doi Saket residents.

But I guess what I was always trying to underline with that release was the limited extent of my experience, that most of the soundscapes I recorded and experienced were things I overheard rather than participated in, and that those limitations heightened some aspects of my experience of Doi Saket and I’m sure caused me to overlook many others.

And how did you approach turning the soundmap of Lost in Doi Saket, which is non-linear in so far as the listener is given agency of the order the sounds are played, into the more fixed medium of Overheard in Doi Saket, an SD card?

And how did you approach turning the soundmap of Lost in Doi Saket, which is non-linear in so far as the listener is given agency of the order the sounds are played, into the more fixed medium of Overheard in Doi Saket, an SD card?

Well really for me I thought about what exactly I wanted to convey with the SD card release with 3Leaves, what did I want it to be in essence, and from there I built some pieces from the recordings I thought most reflected the ideas informing the album, and also picked some particular sections of recordings which form part of the map to appear as stand-alone pieces on the album. Obviously they are very different things the SD card and the map, but I think at heart they centre of the same things, narrative, fantasy, memory, place and emotional and physical mapping.

In speaking with the other subjects of Sound Propositions, as well as in my own experiences as a journalist and artist, I’ve noticed a variety of entrance points into experimental music, but several recur. One of the main ones is punk rock or a related experience of DIY music and shows. Others come from the club scene and techno, but the ethos of DIY seems to be present there too. And then of course there are the visual arts. Am I right that for you your connection to working with sound was more an extension or your artistic interests?

It initially was more of an extension or a supplement to the installation work I was doing, but I guess over time it has come to be obviously the medium with which I work. In addition to working as a visual artist though I did do quite a lot of DJing in the sort of DIY queer alternative scene, so that introduced me to some of the software I now use in my sound work. Over the past year I’ve actually started to miss the visual side of my work, and I am moving back towards incorporating the visual into my sound work. I’m not sure if I already spoke about this, but I’m doing a project now in Spain and also in Belfast which incorporates drawing and field recording.

Did working as a journalist inform your style of composition and interest in field recording in anyway?

Not really. But the excellent thing about working as a journalist when I was in Australia was that I always did a lot of environmental reporting, and through this work I discovered loads of amazing places to record. For example my album Landing Lights is named after this really run down reserve near the airport in Sydney, and I discovered that through writing stories on local people’s attempts to get the area cleaned up so it could function more as a reserve for migratory birds. So there certainly have been lots of advantages. The other aspect of journalism which has informed my practice but more particularly my work with Flaming Pines, is that it has engendered in me the importance of engaging your audience. When I work with artists on FP, I always try and get them to discuss with me the aims of the release; what story is it trying to tell? Or what story can we tell about it which will encourage listeners to engage with it. Obviously there are lots of horrible gimmicky and depressing things about marketing, or pitching a release, but on the other hand it is important to have a respect for the audience and to think about how to present a release in a way which will give listeners an ‘in’ to relating to the sounds and engaging with the themes of the release. So journalism which is really all about justifying ‘why would anyone read this?’ and ‘why would the reader keep reading this’? has certainly helped me at least think about the listener, and how to engage with her or him.

By the way, I wanted to ask you about “the other” Kate Carr, the artist who lives in New Mexico. Have you checked out her work? Are you in touch? Has this created any confusion for you? I only know of one other person with my name, but that guy just seems completely different from me, you know? Like we’re not going to be in competition or confused with one another. So I’m kind of wondering what it’s like to discover another artist half a world away working with the same name. Any possibility of a collaboration? 🙂

Ha! Yes this has been a little strange for me, it is funny with names, I mean mine isn’t super common so I wasn’t really expecting obviously to come across someone with the same name. But there are actually a few Kate Carrs who have a fairly high profile, one in the USA who I think does press work on child safety, and another who I think died of cancer and wrote a memoir about her battle with the disease. So I’ve come to realize my name is not as uncommon as I might have thought! I have certainly seen the visual artist Kate Carr’s work, it is sort of minimal installation type work from what I’ve gathered working with very simple materials. I haven’t seen it within a gallery context just photos online so I wouldn’t say I’m particularly across her output. And although she is in the arts it is obviously very different work to mine, so I don’t think it has created any confusion, at least not for me, and I haven’t contacted her. I know people do get in touch with others with the same name, but it hasn’t really been something which has occurred to me. But you never know!

Ok, so I’d like to follow up a bit more about the specifics of your practice, how you work, and your compositional method. Clearly field recording is a prominent part of what you do, especially since you don’t really identify as a musician or instrumentalist in a traditional sense. You said in another interview you listen to music on your digital recorder, so that way you always have your recorder ready to go. (Are you still riding around on your bike listening to music btw? Sounds dangerous, especially in a city!) Do you tend to turn these recordings into compositions rather quickly after making them? Much of your work seems to be making use of a sense of place, of events in your life, natural or seasonal factors, all of which adds something to the emotional resonance of the work, of how it’s framed for the audience.

Yes I’ve always ridden my bike and listened to music, I think my ears are very good at filtering between the noises of cars and music, so I’ve never not known a car is coming or anything like that. But having said that when my recorder gets to playing actual field recordings of cars, that can be confusing, and I try not to have that happen. But I understand it is not the safest practice in the world! I’ve never learnt to drive, even though this is something I do one day hope to do, so riding has been always something I’ve relied on for getting around, and to do so listening to music really can be a wonderful experience depending on where you are riding!

Sometimes I think I work quickly, and other times I feel like I am super slow. It is hard to gauge really because I’m not that familiar with the working habits of others. Certainly there are a lot of artists who are far more prolific than me, but I think maybe I’m somewhere in the middle. It doesn’t take me several years to do an album, but I’m not putting out eight a year like some manage. And yes definitely my work is very centered on place, on sound and place; the emotionality we bring to places, or are engendered by place.

I think one way I do work quickly is that often I will incorporate field recordings I’ve taken directly into a work sometimes even the same day I take the recording. Or I will go out seeking a particular type of recording for a work already in progress. I am obviously not someone who either likes or desires to have a lot of space from field recordings or to approach them as sounds divorced from the site or process of recording.

Do you also maintain an archive of sounds that you draw from? I read that Aki Onda purposefully distances himself from his archive in order to forget some of those personal associations you spoke of, to (re)approach the recordings with fresh ears.

Yes, Francisco Lopez also takes this approach to his field recordings. For me obviously the idea of forgetting or removing the associations or the feeling of recording in a particular site goes completely against the central themes of my work, so it is not a practice that I personally relate to. This is of course not to say it isn’t valid, and I think for Lopez for example it is the materiality of the sound itself which he is investigating or working with, so the site itself is not important. I recently did a workshop in South Africa which was led by Francisco so he spoke about this aspect of his work. For me however one of the beautiful aspects of field recording is the unique sonics of a particular sites, and the ‘meaning’ or the ‘resonance’ these sounds have, or the stories I want to tell using these sounds flows directly from their origins, how they flow through the recording site, what mood they convey as they reverberate through the space, and my own experience of recording in them. I think this last personal experiential aspect of my work is perhaps fairly unusual in the field recording scene. I’m not at all interested in presenting a set of recording which purport to convey some sort of objective experience of a particular site, what interests me is the coming together of the sonic, the specificity of place and the emotional or experiential process of recording. How does it feel to be in this place hearing these sounds? And how can I use sound to tell a story about that experience? These are probably the two main questions my practice seeks to explore.

But your work is also less improvisational, even if it is through improvisation that some aspects of a composition come together. Can you tell us more about how you compose? Do you get all your pieces together and “play live” and record straight to stereo, or do you carefully arrange ‘in the box,’ editing in a DAW? Or some combination?

I work in different ways. I used to be a lot more structured and place the clips using Fruity Loops, after a while I just loaded all the clips into one frame and just triggered them live and recorded that, and my whole Overheard in Doi Saket album is done that way. In Fabulations I did a bit more of a combination, I had some more structured elements and improvised over the top of those. Instrumentally I usually just record sessions and take clips that I like. I might do part of a piece, then decide it needs some sort of more instrumental section and so improvise based on that. Because I’m not a musician at all, I do sometimes listen back to things I’ve played and think ‘wow how did I do that’ and it would be near impossible for me to repeat it. ‘Beginnings’ off Songs from a Cold Place for example I just played one day that whole piece. But I could not play it again! So luck plays a fairly big role in my work.

And maybe this is a good time to ask about how you approach live performances. Do you see yourself as primarily a recordist, a studio artist, or a performer? Do you draw strict boundaries between these practices?

When I was in Australia there were fairly limited opportunities to present my music live. I think I’ve played all up probably around 15 times maybe. Obviously now I’m in Europe there are more opportunities to do live work, and it is something I really need to grapple with I think. Up until now I for the most part have presented my work either online or via particular fixed media, and on a few occasions via installation in galleries, so live performance work has not really featured. I’ve never really thought in depth about whether I consider myself more a recordist, or studio artist. I guess I would just say I consider myself to be someone who is interested in emotionality, sound and place and in presenting work which explores those themes whether that is via field recording, composed works, or via a more interactive process. I find myself lately definitely thinking more broadly about how to present my work in a way which is compelling and which augments the themes I am exploring, and particularly also about what an ‘album’ is, and how to deploy that concept in ways which resonates either with or against the work I am doing in interesting and productive ways.

I’m fairly uninterested in the digital/analog debate at this point, yet your Computer Fatigue article has a unique orientation to it that I think isn’t so much about a strict digital/analog debate. Like Taylor Dupree and Seaworthy, there’s a complex reality to working with electronics, tape, acoustic instruments, digital recordings, re-sampling sounds, re-amping sounds. It’s not really about if it’s one or the other but the end product having a certain quality regardless of the product. I think there’s a brand of electronic music that really embraced the pristine quality of the digital, the “digital silence” as Richard Chartier has talked about it. Or the ‘in the box’ composing of the grid or the complexities enabled by Max MSP (see my interview with Mark Fell). Your piece seemed to be highlighting the interesting kind of work, generally emotionally affective work, that has embraced the affective quality over precision or technicality, not necessarily artists who have completely forsaken computers or digital recording, electronic apparatuses, etc. This sort of ties back into the question of live performance for me… I am personally not so bothered by, for instance, Mark Fell sitting stoically in front of a laptop, or Tim Hecker completely obscured by darkness or fog. Mainly because the soundsystem, the physical space, and the social aspects (that is, togetherness and shared experience) are all important parts of live concerts for me more than spectacle, performance, or virtuosity. I appreciate human gesture and theatricality and performance, but I don’t think these are all necessary or collapsible to the same thing. Francisco Lopez has an article, “ Against the Stage,” where he argues that electronic music has suffered from the expectation of theatricality and the stage, an arbitrary convention left over from band-oriented music. I wonder if you can speak to this, what your thoughts on the subject may be.

The performativity debate does interest me, and certainly I can see both sides of it. I think my own preference in my work is for there to be an aspect of the performance which incorporates physicality, whether that be physically rendering sounds in a non-digital realm, so in a way which is transparent to the audience, or a performance which incorporates movement or gesture. But I think at the end of the day it is about a mode of presentation which works with the themes or concerns of the work being presented. There certainly is a rational for very digitally pristine work to be presented simply via a laptop in darkness. But for me an argument which simply insists that sitting behind a laptop can be as engaging to an audience as a live band if the audience just adjusts their expectations, is not always one I find compelling. I do think there are or can be challenges in presenting work which is primarily digital live, and these are challenges I need to grapple with, and which many artists have grappled with and found their own solutions. Yes there are expectations about theatricality and performativity which flow from band-oriented music, but that sort of musical presentation continues to engage vast numbers of people because it is affective, immediate and powerful. I’m not saying the audience is always right, or that it is not important to challenge the audience in different ways, but I do think it is a great strength to be able to present your music in a way which fosters engagement, and physicality, gesture, live use of instruments are all ways of doing that which underline the personal, human and unique aspect of live performance in ways which I don’t think laptop performance can do in the same way.

I’m also hoping you can tell us a bit about how you came to found your label Flaming Pines. What made you want to start a label? What goes in to curating a label such as this? Do you have a set of guiding principles or a mission statement, or just releasing stuff by your friends? Based on what you’ve told me about your past running an art space in Australia, I get the impression that creating community spaces, helping promote and celebrate and cultivate other artists is a part of what you do. Am I reading too much into that?

Initially I simply wanted to put out this record of sound art I had curated on the theme of weather data, and I couldn’t really think of a way to do it apart from doing it myself. And it just all sort of came together fairly quickly, I came up with the name and I did a logo that I really liked and I thought maybe I would simply put out this one record, or perhaps just a few compilations. Then I had a disagreement with a label about sampling on Summer Floods, and so I put it out on Flaming Pines and came up with a few compilation ideas, like Burning Palms and Rivers Home and I started receiving some demos so I began to put some of them out also. It was really a very organic unfolding which wasn’t particularly directed in the beginning, apart from wanting to explore a few themes relating to place and subjectivity with the compilations. I definitely enjoy being part of the sound art community, and doing what I can to strengthen that community and support the work of other artists. Connection, community and engaging with the work of other people are all really inspiring for me, and with Flaming Pines, in a modest way, I think I’ve tried to foster some of those things and hopefully support the work of other artists. I think in a field like experimental music, or sound art, it can at times be a little lonely. It is a small field, and obviously not especially mainstream, so having links with other people is particularly important for me in terms of maintaining a belief in what I’m doing, sharing work and ideas, and challenging myself to improve and develop.

Lastly, I wonder if I can ask about gender. Sadly, up until now all of the subjects of Sound Propositions have been male and though I’ve begun interviews with two other women, they have remained uncompleted for various reasons. IRL my friends and I try to be very aware of the way gender and racial inequalities play out in booking shows, creating committees at work, etc. My own punk rock and queer art school kid past has made me sensitive to equity issues, but I think we’ve largely failed in this regard in our work at ACL, and of course more broadly in music and art criticism. Our interviews and reviews gives off the overwhelming impression of a boys’ club, despite intentions otherwise. Though we’ve had occasional female contributors, this is equally true amongst our staff. This can have as much to do with other demands, but it’s something that I think about and that weighs on me. What good are good intentions when nothing changes? In Tara Rodgers book Pink Noises, which was based on her blog with a quite explicit feminist approach, she asked her interview subjects about their own thoughts and experiences as artists. Some mentioned the structural ways sexism has affected their work or their careers. Other resented being primarily identified according to their gender (rather than their work), or being called a ‘lady-composer’ or female artist. I’m interested in what I see as a tension here, which is equally applicable to any identity, I think. The lack of diversity is problematic not only because otherwise great work is going unheard or undiscovered, but because there are aesthetics, styles, and points of view that aren’t being given space. I’m not sympathetic to arguments that essentialize, claiming that particular qualities are ‘masculine’ or ‘feminine’ or otherwise, but I do think that we could benefit from different perspectives that are not (well-)represented, whether it’s gender, class, race or what have you. How can we better respond to structural inequalities and not contribute to perpetuate inequity? How can we embrace diverse identities and approaches to art without essentializing identities?

I think these issues of identity, be they gender, sexuality, class, race or anything else are important to engage with in all aspects of life. Certainly they are things I try and be conscious of in my everyday life, and to educate myself about, and I don’t think it would be too controversial to say they are probably not issues which are particularly front and centre in the world of sound art. Yes there is lots of essentializing when you are a female working in this field, there are reviews which call you a ‘lady’ or attempt to discuss your work entirely through the prism of gender. And it is a shame of course, and I understand often times reviewers or even male sound artists are well-intentioned, but for sure over the years there are aspects of the way reviewers deal with my work, or the way male sound artists have approached my work which I have found disappointing or patronizing. For example I had a guy approach me to take part in a compilation which featured him collaborating with a different female artist on each track, which he was doing as he felt female artists weren’t getting enough attention, and yes that is well-intentioned but it also replicates a very patronizing—almost chaperoning—type approach towards the women artists concerned. I’ve had several male artists congratulate me on my immersion in emotionality in a way which seemed to contrast my work with the more conceptual or content driven work they produced. So there are many ways preconceptions about gender play out in the sound world. Having said that, over the last 20 years there have been huge changes in terms of mainstream ideas about gender, whether that be through an interrogation of masculinity, the massive shift in terms of gay and lesbian acceptance in relation to marriage rights, or more recently the mainstream emergence of the transgender rights movement. I mean it is funny to think Amazon commissioned the Transparent series which certainly attempts a very sophisticated investigation of the experience of a man who decides to transition to living as a woman in later life, or Netflix has Orange is the New Black which is immersed in issues of sexuality, race and gender, and both of these have found mainstream success. But within the world of sound art these issues I would say are yet to be grappled with in the ways they should be, and I think it is the detriment of the scene in general.

Lastly, I’d like to ask about your favorite work outside of sound art or music, what books, visual art, theatre etc you are inspired by and/or find common cause with. Put another way, are their works in other mediums that you feel an aesthetic kinship with?

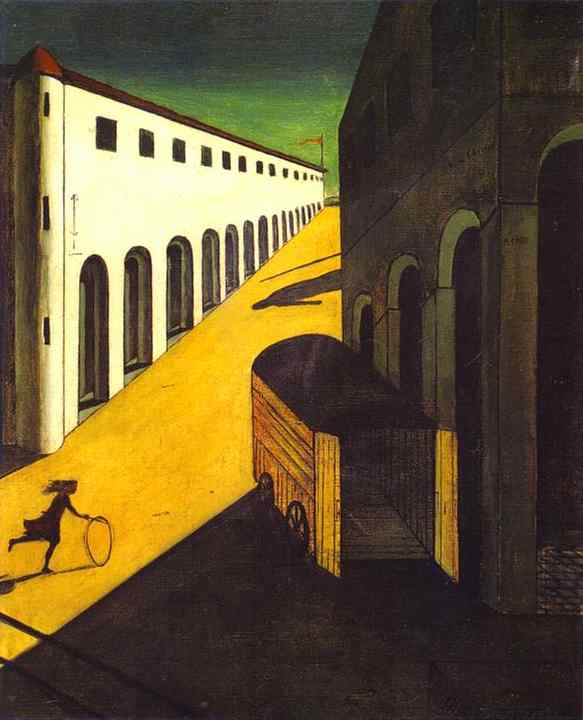

I love the melancholic mystery of Giorgio de Chirico’s work, and the slightly sinister streetscapes and interiors of Edward Hopper and feel there is possibility some commonality in terms of the types of moods I’m interesting in conveying in my work. A more obvious example would be the dream-like aspects of David Lynch’s films. I used to be very into photography, but in terms of my own work I would say I definitely enjoy the foreboding beauty of Bill Henson‘s landscapes, and his interest in interfaces between the rural and urban, which is not really what he is famous for, but they are amazing.

Many thanks to Kate Carr for this fabulous interview. Read more about Kate Carr and her work here.

Reblogged this on Feminatronic and commented:

Really in depth look at the work of Kate Carr here. Courtesy to A Closer Listen for the reblog.

Pingback: Sound Propositions 09: Kate Carr

Reblogged this on The Pacific Northwest Teaching Artist CyberZine..

Pingback: Sound Propositions 09: Kate Carr |

Pingback: Reblog – Sound Propositions 09: Kate Carr — a closer listen | Feminatronic